Books

Personality

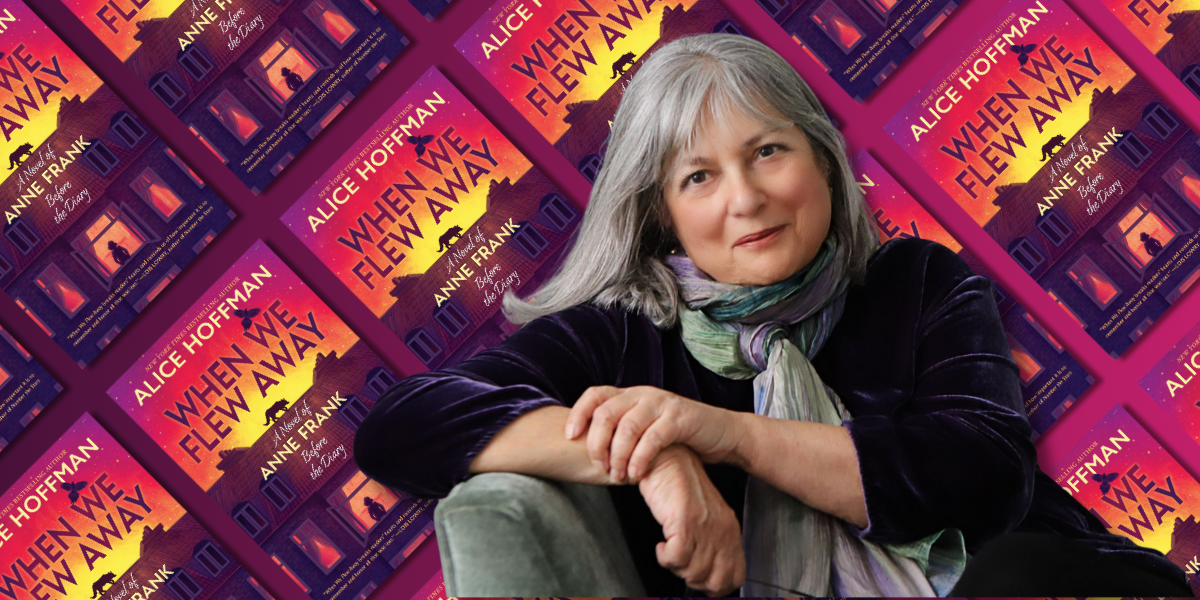

Alice Hoffman Won’t Let Anne Frank Be Forgotten

Alice Hoffman first read Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl when she was 12 years old. Now, 60 years later, the acclaimed author has recreated Anne’s life before the family went into hiding. When We Flew Away: A Novel of Anne Frank Before the Diary (Scholastic, in cooperation with the Anne Frank House) is a heartbreaking middle-grade novel that illuminates the way the world closed in on the Franks, from the moment the Nazis invaded the Netherlands to Otto Frank’s desperate attempts to get his family to safety in America. The author of over 30 novels, Hoffman calls Anne “the greatest first-person narrator in literature” and says her mission is to send readers back to the original diary, which she deems required reading for every child throughout the world.

Hoffman lives outside Boston with her Polish Sheepdog Shelby. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

How did this book come about?

Scholastic approached me, sometime during Covid. There was a sense that there was so much antisemitism, and that Anne was being forgotten. I talked to my 11-year-old niece, who lives in Austria, and she had never heard of Anne Frank. I just couldn’t say no. On a personal level, I began my life as a writer with Anne. At school we only read male writers. It was a big shock to read a book written by a young female voice who was also Jewish. It made me feel like maybe it could happen to me, I could be a writer. Anne’s vision and desires and outspokenness—these are all things that I didn’t know were possible for a girl.

What were the challenges of recreating Anne’s life before the diary?

I tried not to think about the end. To recreate her emotional arc, I had to get to a place where I also didn’t know. There’s this idea that you live your life forwards, but you understand it backwards. People didn’t understand what was happening. It was so horrible; it was so evil that they couldn’t really fathom it. It happened so slowly, and so gradually, and then it happened all at once.

What literary techniques and decisions did you make?

I wanted readers to feel like they were there and to feel what she felt. Sometimes I wrote in the second person (“you”) to include the reader, sometimes in the third person but from inside Anne, and sometimes as a distant fairy tale. Sometimes the evil is so unbelievable that you can only tell it in a mythic way. I also tried to include history without stopping the story as a novel.

There’s a message of hope in your book as well.

In a time of great tragedy, great loss and great evil, nature still exists. There’s still beauty in the natural world: wolves and black moths and rabbits and birds. That’s one of the reasons Anne is such an important voice. True, she didn’t know the end of the story, but she had hope and believed that people were good, that it was possible to change the world. That’s a really important message, especially for young readers right now.

Many of your books feature a mother-daughter-grandmother relationship. Why is that important to you?

To have someone who was behind me and who loved me, no matter what, was of great solace to me, and that was also true of Anne and her grandmother. Grandmothers are also where stories and knowledge come from. My grandmother’s stories about being a Russian immigrant, about waking up with wolves and watching birds in the forest in Russia, always seemed to me like fairy tales.

Tell me about your Jewish identity today.

It’s a big part of who I am in every way, and it’s who I am as a writer. My grandfather was a writer—a poet and a union activist. My bond with my grandparents made my Jewish identity more important to me. I started writing more about Jewish things when my grandmother died. I felt like she was my connection to being Jewish, and when she was gone, I needed to find a different kind of connection.

How emotional was the process of writing the book?

It was a great honor to be asked to write, and it was also frightening, difficult, emotional and sad. When I said yes, I didn’t realize what it would feel like to go to Amsterdam and retrace Anne’s steps, what it would feel like to go to the house where the family had lived before they had to hide in the attic. I had to put those fears aside. I wrote about the beauty that was in her and in her family relationships. Every time I talk about the book, I feel like crying, and I have to hold myself together. In a way, I don’t feel like it’s my book. It’s more about Anne’s book, her diary. Who knows what would have happened to her had she survived, but she wanted to be a great writer—and she is.

Rahel Musleah leads in-person and virtual tours of Jewish India and other cultural events. To learn more, visit Explore Jewish India.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply