Arts

A Floor That Looks to the Stars

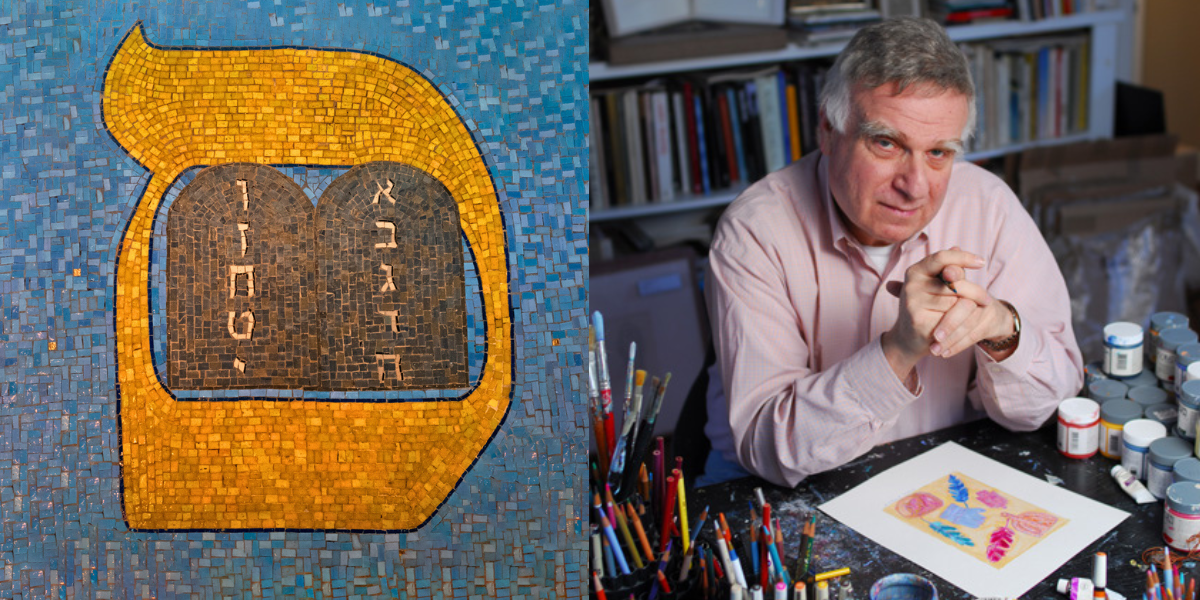

About half a year ago, Dr. Mark Podwal, a New York City dermatologist with a parallel vocation as one of the foremost artists of the Jewish experience, was in Israel visiting archaeological sites when he came across remnants of a mosaic floor depicting the Jewish zodiac in what was once a synagogue.

“In all of early Jewish art, no single motif has aroused more surprise and scholarly interest than the zodiac mosaic floors,” Dr. Podwal said in an interview for Hadassah Magazine in September, less than two weeks before he passed away at the age of 79.

Recreating the zodiac motif in his contemporary yet whimsical style for a mosaic floor in the historic Eldridge Street Synagogue, part of the Museum at Eldridge Street in New York City’s Lower East Side, was Dr. Podwal’s final major public work. He died a few months after its unveiling.

The zodiac is a recurring motif in Jewish folk art and architecture from medieval times to today, linking Jewish ritual and cyclical celebration with local traditions and visual cultures. Mosaic zodiacs have been found in the remains of synagogues dating back to the Roman Empire, and 17th-century synagogues in Poland and Ukraine featured painted zodiac designs on walls and ceilings.

Indeed, it was their use in synagogues that intrigued the artist. “I knew that zodiac iconography turned up in synagogues in Israel from the 6th and 7th century,” Dr. Podwal said. “I decided to do the zodiac floor in a new way.”

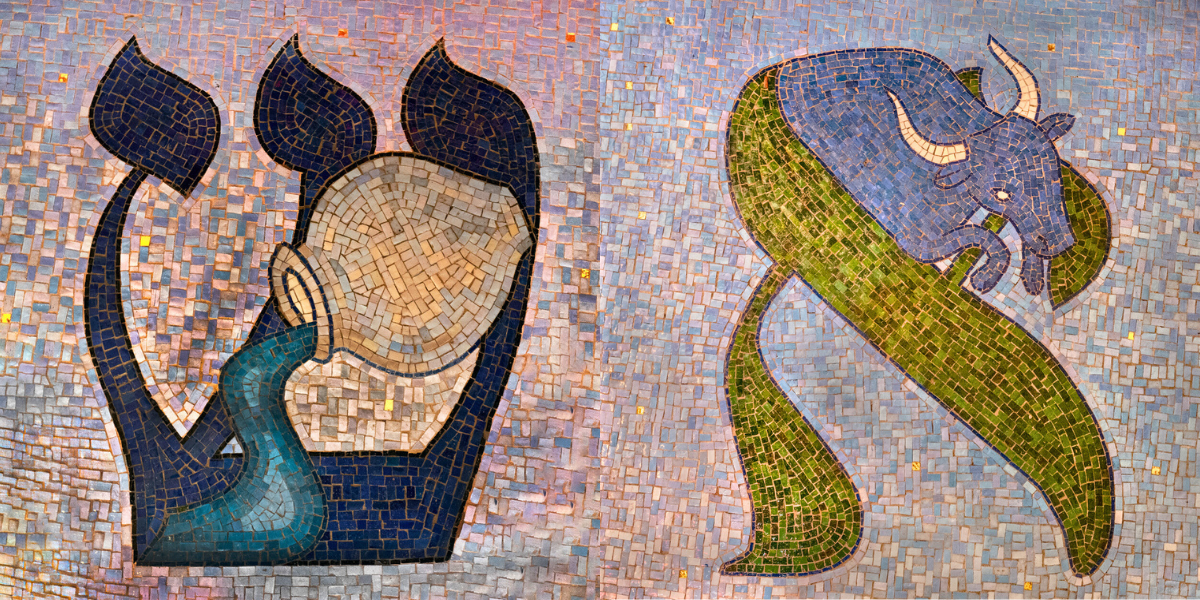

Fabricated and installed by artisans from Progretto Arte Polo, a workshop based in Verona, Italy, the 8- by 24-foot floor, set in a foyer before the main sanctuary, consists of over 300,000 colored tiles. Each astrological sign is imbued with Jewish meaning and paired with a Hebrew letter—the first letter of the Hebrew name of the month associated with that sign—and placed in a rich, blue-tiled background.

Dr. Podwal’s mosaic image of the kaf, the first Hebrew letter in Kislev, is embedded with a bow and arrow; a bow, or keshet in Hebrew, is the Jewish symbol for that month. And since Hanukkah begins in Kislev, the artist used a dreidel as the point of the arrow.

The subsequent month in the calendar, Tevet, is represented by a tet with a capricorn, a mythological creature with the body of a goat and tail of a fish. Here, the sea goat holds a menorah, another nod to the festival of Hanukkah, which extends into the first two days of Tevet.

Dr. Podwal’s art career was launched in the 1970s, when he started drawing political illustrations for The New York Times opinion pages while he was a resident at New York University Hospital. He went on to author and illustrate over a dozen children’s books as well as illustrate many other texts. His art is deceptively simple, employing metaphors and transformations from Jewish legend, history and tradition to convey a host of meanings. One memorable illustration published by the Times and accompanying an essay by Israeli diplomat and politician Abba Eban showed an Israeli tank with a large menorah as its gun turret.

Dr. Podwal, whose pieces are held in nearly 80 museums worldwide, engaged in projects that touched on Jewish joy and pain. He designed Rosh Hashanah cards and decorative plates for the Metropolitan Museum of Art and an embroidered textile for Prague’s 700-year-old Altneuschul. His art was animated for public television in A Passover Seder by Elie Wiesel, who became a close friend, and he designed the Congressional Gold Medal that President Ronald Reagan presented to Wiesel.

Assessing his friend’s career and impact, Dr. Barry Coller, a medical school classmate of Dr. Podwal’s and now vice president of medicine at Rockefeller University, said: “I think he has been the foremost Jewish visual interpreter of our generation. There are many Jewish artists, but Mark plumbed the visual symbols, lore and ethos of Judaism with deep knowledge and artistic mastery. His print series, ‘All This Has Come Upon Us,’ is a searing indictment of centuries of antisemitism.”

That series, created in 2014 for the Terezin Ghetto Museum, includes 42 paintings and drawings. The works span Jewish history from the destruction of the two temples in Jerusalem through the history of persecution in Europe and the Holocaust.

It is that awareness of Jewish history and iconography that Dr. Podwal brought to the Eldridge Street Synagogue.

The mosaic floor is the latest addition to the synagogue, built in 1887 during a period of mass Jewish immigration to the United States, when 75 percent of the 2.5 million Jewish arrivals first settled in the Lower East Side.

The synagogue flourished for 50 years, but beginning in the 1920s, it began to decline as many Jews moved elsewhere. Successful fundraising in the 1980s led to restoration and the founding of the Museum at Eldridge Street. In 1996, the synagogue was designated a National Historic Landmark for its architectural beauty and significance in the American immigrant experience.

Stewart Kampel was a longtime editor at The New York Times.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply