Being Jewish

These Teens Are Keeping Sephardic Culture Alive

Last year, as Judah Roberts was putting up posters for a Ladino festival at Katz Hillel Day School in Boca Raton, Fla., he wished he could involve his peers in preserving the disappearing language. The 16-year-old, who traces his family ancestry to the Balkans, grew up hearing his mother sing songs in the traditional Sephardi language. His family attends Maor David, a Sephardi synagogue in Boca Raton, and his grandmother makes the Sephardi specialty Pescado con Huevo y Limon (fish with eggs and lemon) for most Jewish holidays.

After posting on Facebook that he wanted more young people to learn Ladino, he connected with Ethan Marcus, the managing director of the Sephardic Jewish Brotherhood of America, who had been thinking about ways to engage younger generations. Their mutual enthusiasm led to the launch of Bivas, the Brotherhood’s fledgling youth organization whose name means “live” in Ladino. Roberts serves as national president of the organization, which is coed and open to anyone who identifies as Jewish, with or without Sephardi roots.

“Ladino is on the brink of extinction. It is unsettling to see a culture and history dying out like that, especially among the young generation,” Roberts said. “I was inspired to do something about it.”

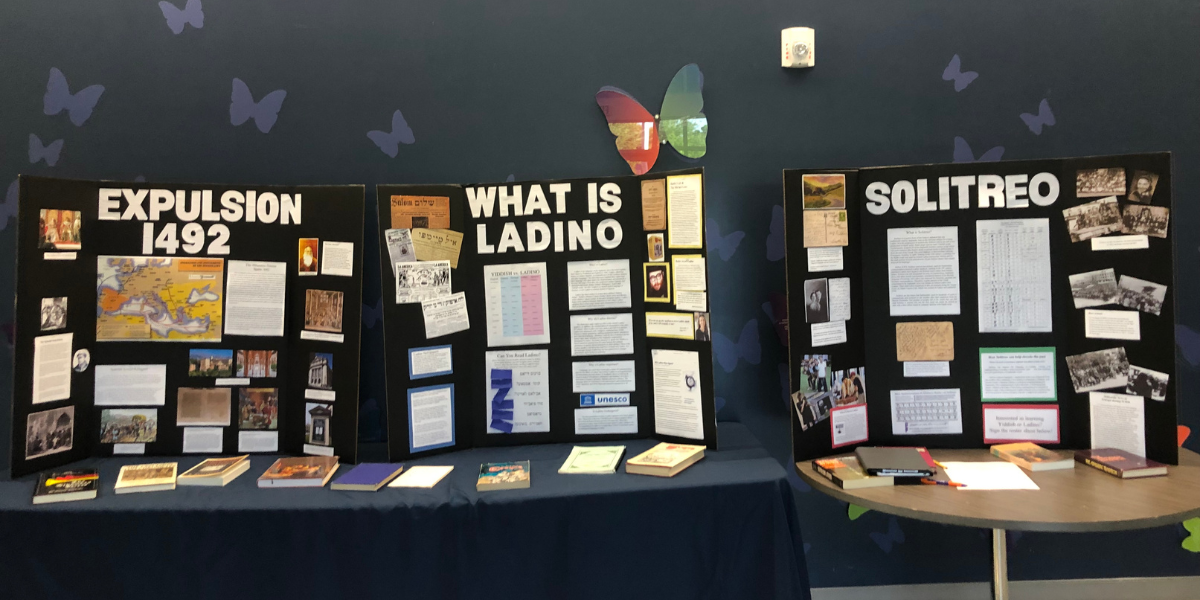

Drawing on youth leaders like Roberts to recruit fellow students, Bivas now has clubs in two Boca Raton day schools as well as ones in Teaneck, N.J., Los Angeles and Seattle, with others set to launch in Philadelphia and Atlanta this year. Clubs host weekly extracurricular activities that feature movie screenings (e.g., Song of the Sephardi, a documentary film), holiday celebrations, boreka bakes or Ladino lessons.

In one example, Roberts organized his club’s biscochos bake, distributing the traditional ring-shaped pastries at the South Florida 10th Annual International Ladino Day Festival. He has also helped organize Bivas shabbatons in New York and Orlando.

Bivas’s quick growth bolsters the mission Marcus envisioned when he resolved to cultivate a younger generation, reversing generations of Sephardi assimilation into the Ashkenazi mainstream in the United States.

“If we don’t do something now, we’re going to lose it,” Marcus said of a community with deep roots in America but few schools or youth institutions of its own. He described efforts to revitalize Sephardi pride as “staying in one’s tradition and being steeped in one’s identity, while fully engaging with the modern world. We want to make sure that’s something we offer to our next generation.”

Hilary Danailova writes about travel, culture, politics and lifestyle.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply