Books

A Tale of Lists and Blacklists

Jerry: Oh good. Anyway, I wanted to talk to you about Dr. Whatley. I have a suspicion that he’s converted to Judaism just for the jokes.

Priest: And this offends you as a Jewish person.

Jerry: No, it offends me as a comedian.

These days, I frequently find myself recalling this famous snippet from a Seinfeld episode. It typically comes to mind each time I encounter yet another virulent pronouncement, petition, post or other manifestation of anti-Israel sentiment in the literary and literary-adjacent spaces to which I belong, from the college campuses where so many writers teach and learn to various publications and journals (and their editors).

The discourse and documents offend me as a Jewish person, of course. But I’m also offended as a writer whose academic training and professional background have emphasized careful research, critical thinking and precise language. I don’t understand how people who ostensibly share my respect for these essential tools can produce and amplify such toxic and poorly founded material.

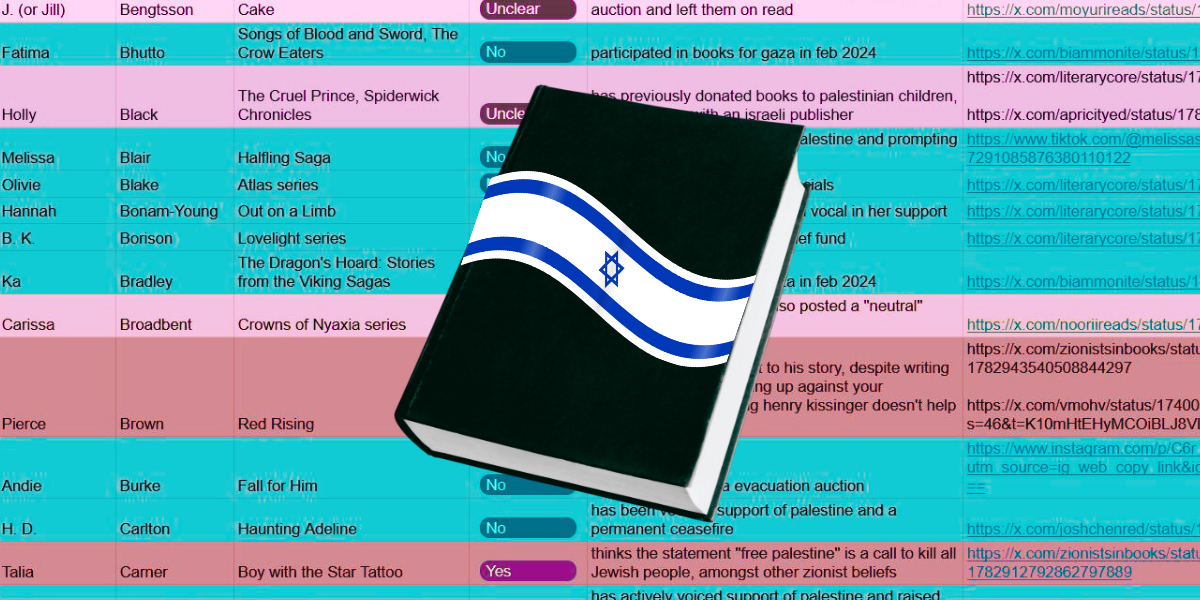

Recently, my social media and private email accounts were deluged with consternation about a spreadsheet titled, “is your fav author a zionist?,” one of a number of similar lists that are found on social media arts and culture spaces. The professional in me winced instantly at both the lack of title case and the abbreviation of the word “favorite” in this public-facing document.

Little is known about the background and credentials of the document’s creator. Her account on the platform known as X (formerly Twitter) only has a first name, “Amina,” and has since been made private. But while the account was public, a post with the spreadsheet was viewed over half a million times. This document and its virality have gotten quite a lot of media attention, including in a JTA article and in other Jewish media.

Citing social media posts as evidence, the spreadsheet purports to declare whether a particular author is “Pro-Israel/Zionist” or “Pro-Palestine/Anti-Zionist”; where cases are “unclear,” intermediary categories may apply.

For those authors found guilty of the sin of Zionism, the document advises, “…you do not give them any money (purchasing their books, streaming their shows/movies) or promote their work on any social platforms.” Those deemed to be “Pro-Palestine/Anti-Zionist,” by contrast, should be supported “as much as you can as most are under fire for their stances.”

Let’s leave aside that concluding assertion—except to note that it’s not difficult to find evidence of sympathy for “Pro-Palestine/Anti-Zionist” perspectives in mainstream media.

I don’t need to explain to Hadassah Magazine readers why this document might offend me as a Jewish person. You’ll likely feel it in your kishkes. What might be more surprising, however, is why it offends me as a writer, a teacher and a literary list-maker myself.

In the aftermath of the horror of October 7, I created two new lists, both available on my website. One, with a broadly educational purpose, I titled “After October 7: Readings, Recordings, and More.”

The second addressed a specific audience: “Writers, Beware,” a nod to an established trade website, Writer Beware®, which warns against “literary scams, schemes, and pitfalls.” Like the trade website, my list had a cautionary purpose: to help writers—especially, but not exclusively, Jewish, Zionist or Israeli writers—approach journals, publishers and other literary spaces with an informed sense of these organizations and groups’ public statements about Israel or Gaza in the aftermath of October 7.

Some may ask how “Writers, Beware” differs from the “is your fav author a zionist?” spreadsheet? It’s a fair and important question.

First: “Writers, Beware” opens with a detailed explanation about what motivated me to launch it:

Sadly, too often within our literary and literary-adjacent communities, expressions of concern for the welfare of innocent Palestinians—concern that I, as well as the vast majority of Jewish and Israeli writers of my acquaintance, share—are compromised by both distortions of the historical record and ongoing demonization of the state of Israel, Israelis, and/or the vast majority of Diaspora Jews who are not anti-Zionists. Too frequently, such expressions cross the line and traffic in misinformation, disinformation, and outright antisemitic rhetoric and tropes. Elsewhere, a pointed absence of concern for Israeli/Jewish welfare—discernible in complete erasure of Israeli/Jewish experience—is equally problematic. All of this is upsetting and dangerous when it happens in any environment; it’s particularly painful for those of us who inhabit writing- and publishing-focused spaces where we esteem prevailing values of both allyship and, importantly, accuracy.

Second, instead of advocating for a boycott campaign, I offer a number of actions for readers to consider, if they share my dismay regarding the amplification of such toxic tendencies in our literary ecosphere. These range from private one-to-one dialogues to quietly refusing to submit work to certain journals or projects as well as publicly expressing upset at the erasure and misinformation in a variety of forums.

There is a third significant difference. “Writers, Beware” doesn’t target individuals; individuals appear rarely, and only when speaking in their professional capacities. Moreover, although it makes use of social media posts and other online materials, including newsletters and open letters, it cites only what I consider “primary sources.”

For example, when “Writers, Beware” references The Feminist Press at CUNY, an independent, nonprofit publishing house, it links directly to that press’s submission guidelines page. The guidelines currently include a “hope to collaborate with and center Palestinian authors, in light of the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the century of Zionist settler colonialism in Palestine.”

Had The Feminist Press simply noted an interest in collaborating with Palestinian authors, it would not have merited inclusion in my list. The additional demonizing and ahistorical phrasing was the decisive factor.

It is the binary between “Pro-Israel/Zionist” and “Pro-Palestine/Anti-Zionist” that The Feminist Press and “is your fav writer a zionist?” present that is problematic. It is—or should be—possible to be pro-Israel and a Zionist and pro-Palestine, to be both concerned for the welfare of Israeli and of the Palestinian people. “Pro-Palestine” should not, by default, mean “anti-Zionist.”

Consider the “is your fav author a zionist?” spreadsheet entry for author Gabrielle Zevin, which mentions that the author “spoke at an event with Hadassah, a self-proclaimed zionist org. character in their book also a Zionist lowkey [sic].”

Following the link provided to document Zevin’s alleged perfidy, you’ll arrive at the X account of a book blogger—not the aforementioned Amina—who shared a post about a One Book, One Hadassah national book club event with Zevin and a social media post from FairyLoot, a book subscription box service, hinting at a controversy about Zevin’s best-selling book Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow.

The book does indeed include a character who is Israeli as well as several Jewish characters, and Zevin took part in a Hadassah Magazine book club event in February 2023. But a Ph.D. is not required to consider the link to a social media post and the unclear line describing the book in the spreadsheet less-than-ideal sourcing to proclaim an author a “zionist.”

Even the “best” of these lists leave room for improvement. “Publishing in Solidarity with Palestine,” another example (from writers @emilystoddard and @thetinydynamo, both on X), is much more professionally presented. But even while directing writers to individual press or journals that support Palestinians, it doesn’t consistently link to those outlets’ own statements. More troublingly, it, too, seems unconcerned with elisions between “solidarity with Palestinians” and virulent anti-Israelism.

All this points to patterns that we’re encountering in so many spaces since October 7. Yes, the anti-Israelism that so often crosses the line into antisemitism disturbs me as a Jewish person. But the accompanying inadequate research, tendentious writing, distorted historical presentation and overall intellectual sloppiness offend me as a writer and teacher, too. Perhaps Amina, the spreadsheet creator, has even begun to perceive her own work’s flaws: By early June, the spreadsheet had been temporarily taken offline, leaving just a message that it was undergoing “renovation” and would return “soon.”

What does this mean for readers, writers and lovers of Jewish literature out there? It’s difficult to say. But this much seems clear: These are not ideal times for many Jewish, Israeli or Zionist writers. Your support means more now than ever.

Erika Dreifus is the author of Birthright: Poems and Quiet Americans: Stories, which was named an American Library Association/Sophie Brody Medal Honor Title for outstanding achievement in Jewish literature. A fellow in the Sami Rohr Jewish Literary Institute, Erika teaches at Baruch College/CUNY and speaks and writes frequently on literature and publishing, particularly in Jewish contexts.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

[…] this week did bring the publication of “A Tale of Lists and Blacklists,” an essay commissioned by Hadassah magazine. (In case you […]