American View

When Women Couldn’t Eat at the Plaza

Many of us who were pioneers of the women’s revolution of the 1960s and 1970s have stories about an embarrassing exclusion from a men-only facility. My experiences led me to mobilize the National Organization for Women (NOW) for action against the famous Plaza Hotel in Manhattan.

In November 1968, as head of the television and radio department of my public relations agency, I’d arranged for a client to be interviewed by a reporter at the Plaza’s elegant Oak Room, where I’d eaten dinner on several occasions. When the three of us arrived at the entrance to the restaurant at 12:30 p.m., the maître d’ stopped us at the door.

“Is Muriel Fox a woman?” he asked. “Nobody told me that. Sorry, we don’t admit women for lunch.”

I didn’t make a fuss in front of my client. Instead, I quietly led my guests down the hall to another Plaza restaurant. It was a humiliating experience.

At the next meeting of NOW’s New York City chapter, I proposed that we picket the Oak Room. The suggestion was greeted with loud cheers and an immediate resolution to call the action for February 12, 1969. National NOW had proclaimed the week starting Saturday, February 9 “Public Accommodations Week.” Chapters throughout the country scheduled eat-ins and drink-ins to protest women’s exclusion from restaurants and bars. They were taking a page from lunch counter sit-ins of the civil rights movement.

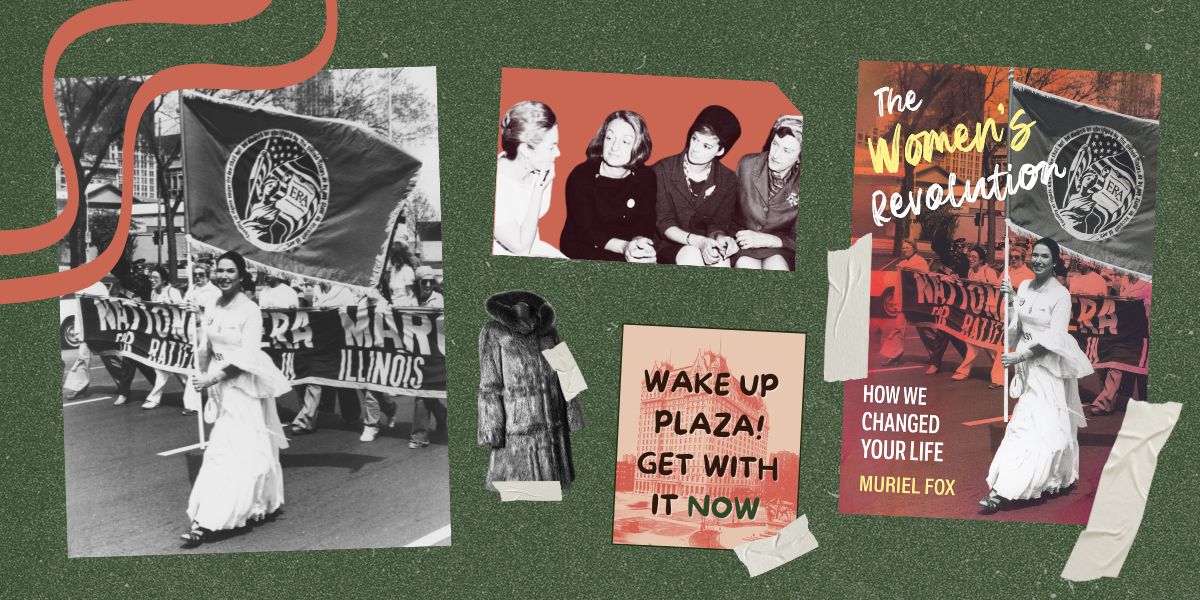

I advised our members to dress for the protest as if they’d always belonged in the Oak Room. “If you have a fur coat,” I told them, “wear it.”

We alerted the press, which turned out in force. At noon on February 12, fashionably attired NOW members paraded through the lobby outside the Oak Room entrance. Our signs read: “Wake up PLAZA!” “Get with it NOW!” and “The Oak Room is outside the law.”

A group of women snuck inside and commandeered a large round table. Four waiters promptly removed the table, leaving the women seated in a circle with nothing in between. During all the hubbub, male customers continued eating their lunch.

Betty Friedan arrived at the last minute—with a black eye! She and her husband, Carl, had been fighting (the couple had a stormy relationship, physically fought often and ultimately divorced after 22 years of marriage). Jean Faust, past president of our chapter, was an expert in cosmetics and applied pancake makeup to her face to cover the black eye for TV interviews.

Sixty press people showed up for our protest at the Plaza. I recall one beautiful young reporter introduced herself to me. “I’m Gloria Steinem from New York Magazine,” she said.

Gloria had not yet proclaimed herself a feminist in public. At that point, she still preferred the term humanist.

That night, our demonstration appeared on several TV newscasts and was covered in major newspapers. Several months later, the Plaza backed down and opened up the Oak Room to women for lunch.

While our highly publicized protest played a role, the Plaza’s surrender was due mainly to a mandate from New York City’s Human Rights Commission, headed by Eleanor Holmes Norton, an activist and feminist who was later elected to Congress from the District of Columbia.

On the first day that women were permitted in the Oak Room during the day, I ate lunch there with my brother, Jerry Fox. Nothing unusual happened, and none of the clientele seemed aware that history was being made.

Betty and I were among the Jewish women who participated in the fight to give women full access to the Plaza. We were also among the Jewish feminists who helped co-found NOW, which in turn helped create profound global changes for half the earth’s population.

The momentum of the worldwide feminist revolution had been set in motion on October 29, 1966, when NOW was founded. The organization began just three years after Betty published The Feminine Mystique, arousing millions of educated women everywhere to expand their lives beyond the boundaries of the home.

Betty served as president of NOW for its first four years. She gave our organization its name, its inspiring Statement of Purpose, its strategies and its ferocious energy. With a cohort of other leaders, including Black women and civil rights activists, she directed our amazingly rapid expansion from an elite cadre to a force of hundreds of thousands of dedicated activists.

The feminist movement taught us to avoid false modesty, so I include myself as a NOW co-founder. Betty recruited me, an officer of a major public relations firm, to do the publicity that introduced our new movement to the world media. I served as her lieutenant during the nascent stages of the second-wave feminist movement. In later years, I was national chair of NOW, founder and president of the NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund (now called Legal Momentum) and founder of NOW’s New York chapter. I now chair Veteran Feminists of America.

Sonia Pressman Fuentes, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission attorney who served as an invaluable adviser in our early lawsuits, estimates that she and I were among the 12 to 13 percent of NOW’s founders who were Jewish—although we can’t be sure about the religious affiliation of everyone involved. Sonia and I are, I believe, the only major participants of any religion in NOW’s founding conference who are still alive.

Some other lesser-known early Jewish leaders of NOW include Karen DeCrow, an attorney who led militant actions against restaurants and bars that excluded women. She served as the fourth president of NOW from 1974 to 1977. There was also Gerda Lerner, an academic active in the founding years of NOW’s New York chapter who wrote 10 influential books on women’s history, all from a feminist perspective.

Why did we Jews do it? I, a life member of Hadassah, credit the Jewish tradition of tikkun olam for the feminist activism of Jewish women. Also, as Betty pointed out to me and elsewhere, Jewish women through the ages have toughened themselves to be “strong, energetic and supportive.” Think Bella Abzug and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, also a life member of Hadassah, leaders in the revolution that NOW started. They—and we—have trained ourselves to get results.

We can appreciate how much women have accomplished in the past six decades, beginning with Betty’s leadership in 1966, as we look back on employment issues alone. Back then, employment ads would say “Help Wanted Male” or “Help Wanted Female.” Women comprised only 4 percent of America’s lawyers, 7 percent of its doctors and 1 percent of its federal judges. Look around and see how much we’ve changed the world for women since then.

Muriel Fox, a life member of Hadassah, is the author of The Women’s Revolution: How We Changed Your Life, from which this piece is adapted.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Susanna Levin says

NOW may have had a plethora of women founders, but NOW turned its back on Jewish women with its complete silence on the rape and hostage taking of Jewish women on Oct. 7.

Hadassah should not be singing the praises of this tarnished organization.