American View

They Also Served

The unassuming brick exterior of the National Museum of American Jewish Military History, located in the Dupont Circle area of the nation’s capital, belies the wealth of information found inside. Its carefully curated core exhibition leads visitors through the history of American conflicts by focusing on the vital military role Jews have played from colonial days to the present.

It’s impossible to provide the exact number of Jews in the armed forces past or present—one of the most frequently asked visitor questions, according to Pam Elbe, the museum’s head of acquisitions. “The government doesn’t require service members to provide their religious affiliation,” she said. “There are currently about 8,000 self-identified Jews in the military although there could be more who haven’t declared. What we do know is Jews have served from day one.”

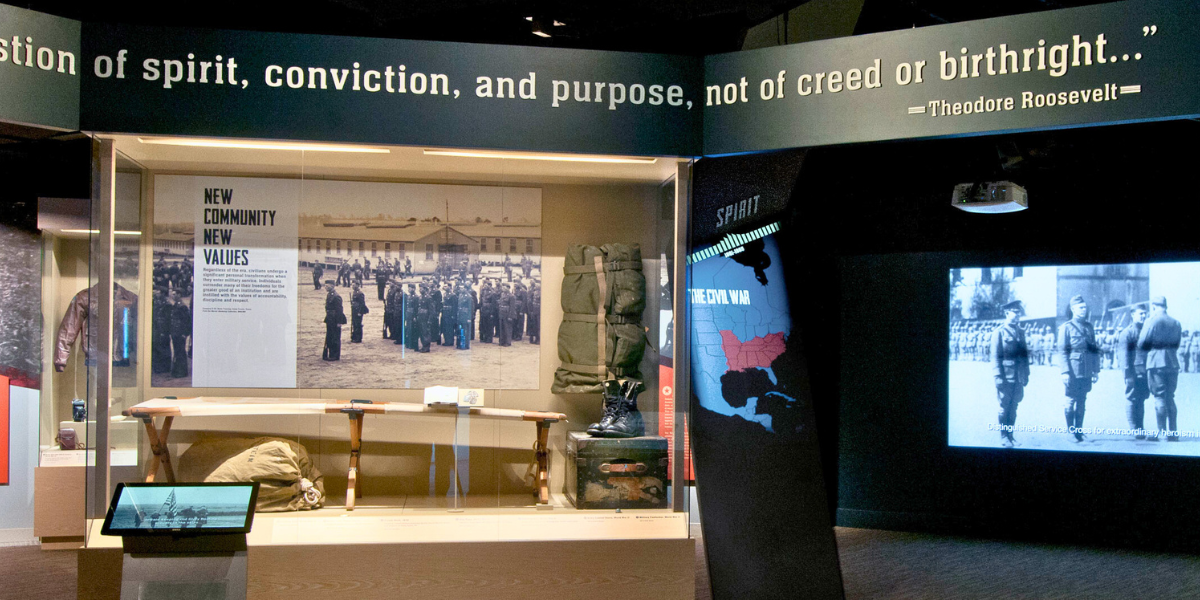

Written on the wall at the opening to the core exhibition, titled simply “Jews in the American Military,” is a quote from Theodore Roosevelt: “Americanism is a question of spirit, conviction, and purpose, not of creed or birthright…”

His message resonates throughout the intimate museum and its core exhibition, exemplified by individual stories of Jews who served. These include immigrants who joined the military in appreciation of their new country, such as Polish-born Lt. Frances Slanger, who came to the United States as a child. She was one of the first nurses to wade ashore at Normandy shortly after the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944.

The core exhibition, which includes interactive displays as well as documents, photos and artifacts such as war diaries and religious objects from kippot to Torah arks, occupies the entire main floor. Its five sections are largely organized chronologically—Answering the Call (pre-Civil War), Spirit (Civil War through World War I), Conviction (World War II), Purpose (Cold War to present) and Leaving the Service (life as a veteran). Smaller permanent exhibits, including the Hall of Heroes, which showcases recipients of the Medal of Honor, are located on the lower level.

Founded by the Jewish War Veterans of the USA and opened in 1988, the museum is funded by private donations and memberships. While it provides an excellent overview of American military history, the individual narratives are what best highlight the contributions of Jewish service members.

“History comes to life with a personal touch and a human face,” said Elaine Bernstein, the museum’s president. “The artifacts are no longer just ‘things’ in a glass case. They represent real people with real tales of valor.”

Among the tales are the stories of 30 female veterans.

Slanger, who is mentioned in the Conviction section, was one of the first nurses to die in Europe during World War II. She was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart. Hours before she was shot by the enemy, she sent a letter to Stars and Stripes magazine praising G.I.s for their bravery: “These soldiers stay with us but a short time, from ten days to possibly two weeks. We have learned a great deal about our American boy and the stuff he is made of….”

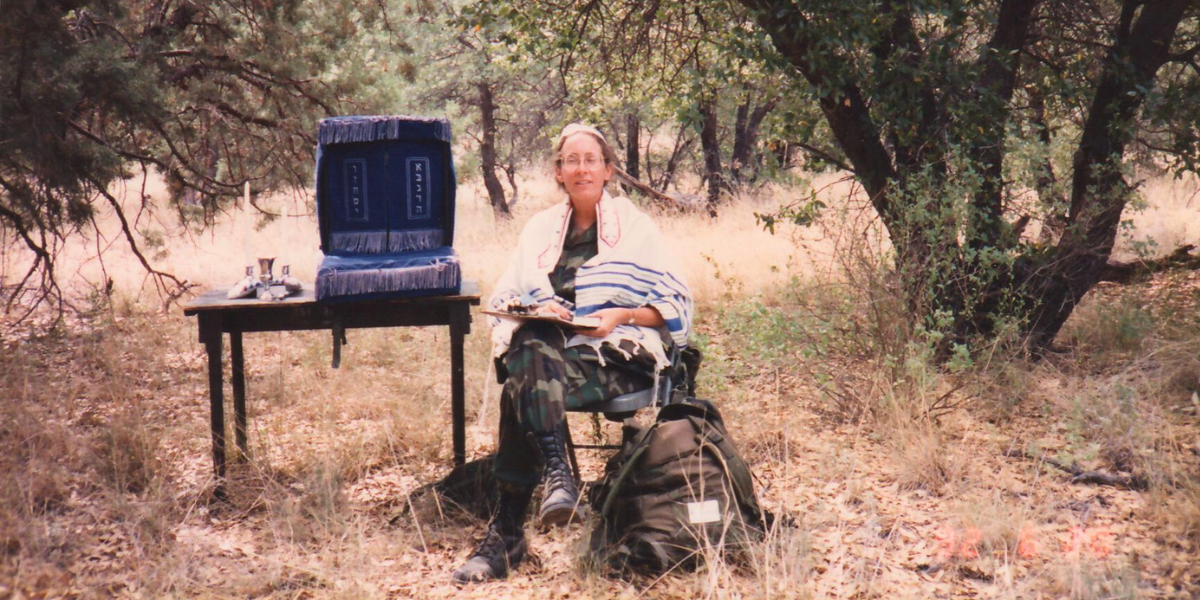

The story of the first Jewish female military chaplain, Rabbi Bonnie Koppell, appears in Purpose. She joined the United States Army Reserves in 1978 and was ordained in 1981 by the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College. She served in Operation Desert Storm (1991) and Operation Noble Eagle (2003), and, over the course of her military career, was deployed to Iraq, Kuwait and Afghanistan to conduct religious services. Now retired from the military, Koppell, who rose to the rank of colonel and received many awards, is associate rabbi at Temple Chai in Phoenix.

To specially honor Jewish servicewomen, the museum is planning an exhibition focused on their narratives in 2025.

The stories in the museum, from the heroic to the everyday, serve to debunk antisemitic tropes such as “Jews aren’t patriotic” and “Jews don’t serve.” Indeed, Jewish War Veterans was established in 1896 by Union Army veterans to combat accusations that Jews didn’t fight in the Civil War. In truth, thousands of Jews fought on both sides, said Bernstein.

“With the surge in antisemitism, the museum’s mission is more important now than ever,” she added.

The museum houses over 5,000 objects that represent Jewish participation in almost every American conflict, from the colonial era until today. Among those objects, for example, are a soldier’s handbook from the Spanish-American War and a camouflage kippah made of tent material and provided to Jewish Marines for High Holiday services during the Vietnam War.

“Artifacts are a tangible connection to the past,” said Elbe, head of acquisitions. “Our goal is to chronicle the experiences of service members of every rank and military branch. We look for artifacts that uniquely define life in the military.”

In a display of wartime souvenirs is a coconut mailed from Guam during World War II by airman Seymour Silverman to his daughter Marita.

“Coconuts were exotic then,” Elbe explained, “and it speaks to deployment thousands of miles from family.”

Marita Silverman Bowden followed her father into the military. She served as a captain in the Army Nurse Corps in Vietnam in the early 1970s; her service is also chronicled in the museum. Now 80, Bowden remembers how her friendship with other Jewish military personnel in Da Nang lifted her spirits on Shabbat after long hours working at the hospital.

“I’m grateful the museum included me with the other military women,” she said in an interview from her home in a Tucson, Ariz., suburb. “It’s important to preserve stories, otherwise our experiences can be lost to time and conjecture.”

Adrienne Wigdortz Anderson is a Southern California-based freelance writer. The cloth-covered journal her father, Louis T. Wigdortz, kept when a prisoner-of-war in Stalag Luft III is on display in the National Museum of American Jewish Military History.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Janet Nadel says

Great article. So interesting and informative.

Bonnie Levitt says

Rabbi Koppel is a remarkable woman.