Arts

Books

Jewish Poetry’s Renaissance—and Challenges

When poet Jessica Jacobs first conceived of an organization dedicated to Jewish poets and poetry, she did not foresee that the nonprofit literary group she would create would become a lifeline.

Based in Jacobs’ hometown of Asheville, N.C., Yetzirah: A Hearth for Jewish Poetry takes its name from Jewish mysticism. According to the Kabbalah, existence is composed of four worlds. Yetzirah is the world of formation, where things that are created by man take their form and shape. Jacobs and her board found inspiration from that kabbalistic notion to explore poetry, helping Jewish writers transform language into art. The organization coordinates poetry readings, maintains a database of Jewish poets and helps poets working with Jewish themes identify literary journals open to publishing their work.

Earlier this year, Yetzirah also provided a safe physical space for Jewish writers. During the February 2024 conference of the Association of Writers & Writing Programs (AWP) in Kansas City, Mo., a major annual event, a group called the Radius of Arab American Writers had urged all panel moderators and bookfair attendants “to acknowledge the ongoing genocide in Gaza,” according to the group’s social media, and, with other groups, mounted a vocal anti-Israel protest.

Yetzirah’s presence became indispensable at the bookfair, said poet Yerra Sugarman, whose 2022 poetry collection, Aunt Bird (Four Way Books), about her aunt who had died in the Krakow Ghetto, was a National Jewish Book Award finalist. Yetzirah’s table was a “welcoming space for Jewish poets and writers who sought a place of refuge from AWP’s antisemitic atmosphere,” she said. Sugarman, who lives in New York City, was working at the table, and noted that many Jewish writers gathered there to commiserate.

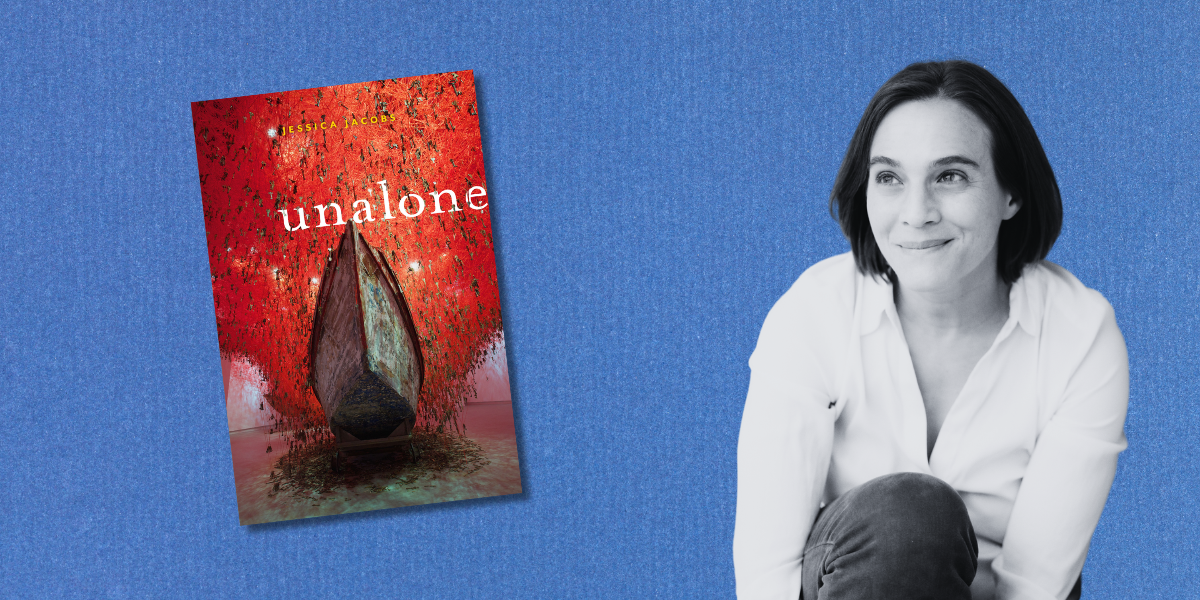

While Yetzirah officially launched in 2022, its “groundwork was laid during the Trump era, in the aftermath of the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, when it seemed vital to have a space in which Jewish writers felt welcome to show up as their full selves, as poets and Jews,” said Jacobs, who chairs Yetzirah’s board. She has just released her own book of poetry, unalone: Poems in Conversation with the Book of Genesis (Four Way Books), a lyrical commentary on the 12 Torah portions in Genesis.

“Since October 7, this community has felt even more essential,” she added.

The anti-Israel sentiment at the AWP conference and Yetzirah’s added mission highlight two trends impacting the Jewish literary world. One is the rise of antisemitism in the arts world, grown more prevalent in the aftermath of Hamas’s attack on Israel on October 7, with individuals and groups in fields from film to literature taking sides in the conflict. The result is that Jewish creatives can feel uncomfortable in or are sometimes even shut out of arts spaces.

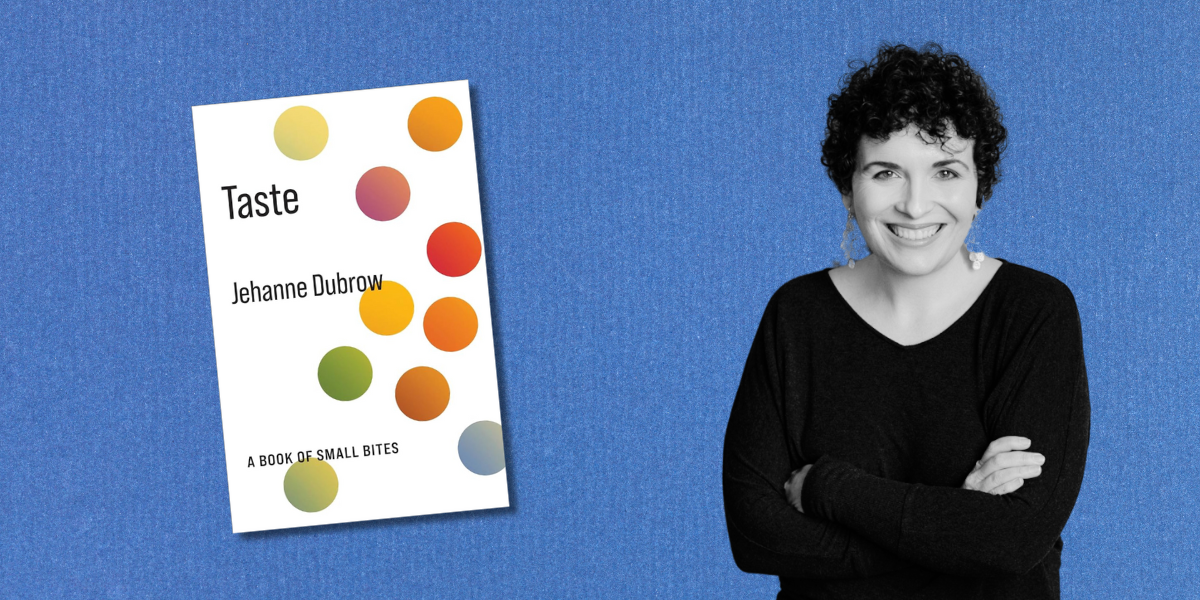

The protests at the AWP conference reflect a larger story “about the growing hostility toward Jewish writers in public spaces and on the page,” said Jehanne Dubrow, vice president of Yetzirah’s board, author of nine poetry collections, including her 2022 Taste: A Book of Small Bites (Columbia University Press) and professor of creative writing at the University of North Texas in Denton. (In response, the Jewish Book Council, one of the longest-running American organizations devoted to Jewish literature, is asking those in the book world to report to JBC any antisemitic literary-related incidents so they can track such occurrences.)

The second trend is a general surge of interest in poetry, a phenomenon that had a 2021 CNN digital article proclaiming a “new golden age for poetry.” According to a 2022 survey from the National Endowment for the Arts, reading and listening to poetry, generally a niche medium, has nearly doubled over the past 10 years. With the help of Yetzirah and other literary organizations, that interest has extended to the Jewish world.

Despite the troubling arts environment for Jewish writers, Dubrow is optimistic about the future of Jewish poetry and Yetzirah. She said the group inspired her to “rededicate” herself to writing Jewish poems. “Yetzirah has fired up the Jewish poetry community,” Dubrow said. “We are seeing so many more Jewish literary events answering the need to support and mentor Jewish poets at all stages of their careers.”

Indeed, Yetzirah’s online listings point to Jewish literary festivals and organizations that showcase poetry collections, such as the Jewish Book Council; Voices Israel, a space for Israeli poets who write in English; and the Jewish Poetry Project of Ben Yehuda Press, which publishes contemporary poetry on Jewish themes.

What makes a poem Jewish? “What we say in Yetzirah’s reading series,” Jacobs, Yetzirah’s founder, asserted, is that “Jewish poets write Jewish poems. If you had asked me 10 years ago if my first two books were Jewish books, I would have said ‘No.’ But looking back at those poems, I realize I was absolutely looking through a Jewish cultural lens.”

Her compilation unalone, however, is steeped in the midrashic tradition of creating commentary on Jewish texts. The opening poem, “Stepping Through the Gate,” begins with the line, “Make a fence, said the rabbis, around the Torah.” The fence evokes protection and guardianship of the Torah, aiming to keep Torah and its values at the center of people’s lives.

Near the end of the poem, Jacobs describes opening a metaphorical gate in that fence, one with “an easy latch and well-oiled hinge” to allow for personal interpretations of seminal Jewish texts.

In the poem “Why There Is No Hebrew Word for Obey,” Jacobs presents visceral images of Isaac bound up as his father, Abraham, imagines the horror he is visiting on his child:

his legs, wrenched back his arms, knotted his ankles to his wrists,

and laid him on that altar like a child falling

through the sky.

Later in the poem, Jacobs memorializes the 11 victims of the Tree of Life massacre in Pittsburgh on October 27, 2018. The Torah portion that Shabbat morning included the binding of Isaac.

For Deborah Leipziger, a Boston-based poet and founder of the 15-year-old New England Jewish Poetry Festival, “Poetry is central to Jewish liturgy and the Bible. It’s part of Jewish DNA.”

This year, Leipziger is both a Community Creative Fellow, as selected by the Massachusetts-based Jewish Arts Collaborative, and the 2024 poet in residence at the historic Vilna Shul in Boston. She is also a proud mother of three daughters, an accomplished baker and a climate activist. All these identities feature prominently in her poems. Her latest collection, Story & Bone (Lily Poetry Review), includes lyrical, reflective poems about family, identity and nourishment.

Among the standout poems in the collection is “How to Make Challah.” That piece, Leipziger explained, reflects her fascination with recipes and their accompanying rituals. She made challah weekly with her daughters when they were young, and came to know the recipe by heart:

Bring the biggest bowl you have,

large enough to contain your whole week.

You’ll need to wrestle with angels.

Begin in the place of knowing, the place that venerates.

Kavannah

“There is a renewed interest in Jewish identities, and that feeds into Jewish poetry,” said Hadara Bar-Nadav, a professor at the University of Missouri in Kansas City and the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in Poetry and the Lucille Medwick Award from the Poetry Society of America as well as other honors.

The titular poem of Bar-Nadav’s new book, The Animal Is Chemical (Four Way Books), alludes to the global refugee crisis. Other poems address her medical trauma. Bar-Nadav has four herniated discs, which can leave her unable to walk for weeks or months at a time. Her poem “Ventriloquist” begins:

The old wound is speaking

again through my back,

carving its blood alphabet.

She transformed the acknowledgements section of her book into a poetic memorial to her grandmother’s 11 siblings murdered in the Holocaust, their specific causes of deaths unknown. Bar-Nadav said it was the only way she could imagine honoring these family members. In addition, she gave them a proper burial in her prose poem “Mindfield,” declaring:

No history here. No death. No sibling. Eleven who never disappeared in the

Camps. I did not know them. They were never born. Eleven nameless question

marks.

Bar-Nadav, who credits Yetzirah for the current renaissance in Jewish poetry, praises the organization for its acceptance of Jewish poets from across the political spectrum. Indeed, in its effort to be inclusive, its events have showcased works reflective of different Jewish denominations and from poets at different points in their careers. And the organization validates the Jewish community’s collective trauma after October 7.

“We want to acknowledge the lineage of Jewish trauma,” said Jacobs, “as well as the fraught ache of the present, while also celebrating Jewish joy and resilience.”

“Yetzirah needed to offer insight and support,” Dubrow said. “Poetry is not an art form of hot takes, but an art form of deep meditation. The board took the time to figure out how we could support Jewish writers in a time of crisis and still be useful to all Jewish poets regardless of their political perspectives.”

Among such initiatives was a guide that Yetzirah developed to help Jewish poets run in-person poetry salons, helping poets create a local nurturing community and making them feel less isolated.

Under Jacobs’ leadership, Yetzirah continues to build community. It launched a membership program in September 2023 and now has a subscriber list of over 1,300. The organization held its inaugural literary conference last summer in Asheville, with over 50 people attending in person; its second conference is scheduled for early July. Dubrow says the conference served as a cornerstone for the organization.

Hundred have also attended, via Zoom, the Yetzirah Reading Series, which features readings by mainstays in the Jewish poetry community such as Grace Schulman, Alan Shapiro and Jacqueline Osherow.

Dubrow captured the spirit of Jewish poetry when she said, “A Jewish poem is full of argument and inquiry. It offers a complex vision of the world, and it doesn’t necessarily have to engage with overtly Jewish subject matter. The idea that where there are two Jews, there are three opinions, is a Jewish poem, too.”

Judy Bolton-Fasman is the author of Asylum: A Memoir of Family Secrets.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

[…] news, and as National Poetry Month draws to a close: Judy Bolton-Fasman’s new article for Hadassah cites “two trends impacting the Jewish literary world. One is the rise of antisemitism in the […]