Books

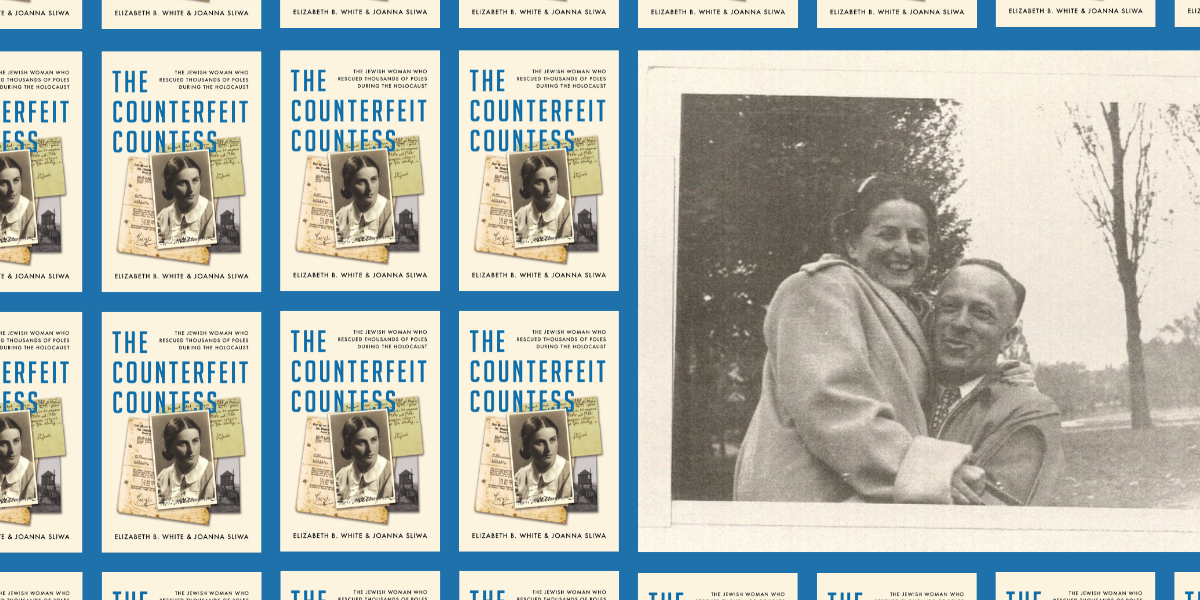

‘The Counterfeit Countess’

The Counterfeit Countess: The Jewish Woman Who Rescued Thousands of Poles During the Holocaust

By Elizabeth B. White and Joanna Sliwa (Simon & Schuster)

The titular “countess” of this remarkable new Holocaust account was a mathematics professor who believed that it was worthwhile to risk one life to save many, even if that life was her own. Her name was Janina Mehlberg. A Jew, she posed as Countess Janina Suchodolska after the Nazi occupation of Poland. In that role, she saved thousands of Poles imprisoned at the Majdanek concentration camp.

The story of how, in her guise as a Catholic aristocrat, she became an officer in the Polish resistance is brought to life by historians Elizabeth B. White and Joanna Sliwa. Just as interesting as Mehlberg’s story is the circuitous route by which the two came to discover and publish her tale.

In the early 1960s, by then living in the United States and working as a professor of mathematics at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Mehlberg wrote a memoir but was unable to get it published. Decades later, after Mehlberg passed away, a professor at the University of Florida who had been given the manuscript by Mehlberg’s husband, Henry, forwarded it to White. He was aware that she had recently presented a paper on Majdanek.

As the book explains, White had known about the countess, but she still found the specifics detailed in the manuscript unbelievable—including that a Jew, in disguise, was able to get food and medicine into Majdanek and even persuade Nazi officials to release prisoners.

White’s efforts to confirm Mehlberg’s account independently were unsuccessful until 2017. At that time, White, employed by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, reached out to Sliwa, a Holocaust expert focusing on Poland, for assistance. Together, using the memoir and extensive research, the two fleshed out Mehlberg’s life before, during and after the Holocaust. In many ways, what they reveal in The Counterfeit Countess defies belief.

Mehlberg was the daughter of a wealthy Jewish landowner in Galicia, Poland. She and her philosopher husband, Henry, lived comfortably as professors at a college in Lwów—today Lviv, Ukraine—until Germany invaded Poland in 1939.

As part of Hitler’s pact with Stalin, the city was initially under Russian rule, and the Mehlbergs were mostly undisturbed. But once Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in 1941 and the Nazis claimed Lwów, their lives became untenable.

As their survival was threatened, it was Mehlberg’s ability to stand up to Nazi threats that saved them. To give one example: When the Jews were being forced into a ghetto, the couple arranged to flee Lwów for Lublin, but Henry was detained by a German official. His wife argued so strenuously with the official in perfect German that he let Henry go. Her philosophy, she wrote in her memoir, was: “You must not toady to them. You must not let them sniff blood.”

The Mehlbergs were able to reach Lublin thanks to a friend of her father’s, Count Andrzej Skrzynski, who promised her identification papers.

He did more than that. He provided them with entirely new identities as Polish nobility. Through chutzpah and her leadership role in the Polish Main Welfare Council, Mehlberg not only supplied needed food and medicine for prisoners, she also was able to sneak out information for the Polish resistance movement.

One troubling note about Mehlberg’s efforts is that they were largely directed toward non-Jewish Polish political prisoners in Majdanek, who did indeed endure harsh conditions. White and Sliwa do not offer a reason for Mehlberg’s focus on non-Jews, but we can conjecture.

Perhaps it was because the resistance organizations she worked for didn’t welcome Jews, and did not know she was Jewish, and that delivering aid to the Jewish areas of the camp posed significant difficulties.

In the greatest irony described in the book, after the war, “Janina was still popular with the people of Lublin…but if she revealed now she was not the countess she pretended to be, but a Jew, it might tarnish her reputation.”

The Counterfeit Countess is a remarkably well-researched, well-told story about a previously unknown hero of World War II. With its descriptions of Polish pogroms before and after the war, it is also a reminder that when it comes to antisemitism, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

To quote Mehlberg in a section from her memoir included the final chapter of the book: “Now, years later, I try not to judge but simply to report, since we who continue as members of the human race are obliged to know its capacities, however grim and unbearable the knowledge may be.”

Curt Schleier, a freelance writer, teaches business writing to corporate executives.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply