Books

Heroes, Hadassah and Jewish Unity at the Seder

This Passover, our seder discussions are bound to swing between the two lodestones of American Jewish life: Israel and the United States.

It comes as no surprise that new Haggadot have emerged to aid in the debates around our concerns for the land of Jewish rebirth and our fears and hopes in the Diaspora. What is a revelation as well as a delight, however, is how distinctly the latest offerings—The Promise of Liberty, The Chinitz Zion Haggadah and Seder Interrupted—reframe the seder experience, pointing to fresh stories, new heroes and different ways of thinking about Passover. And each will help navigate a seder night that will likely feel different from all other seder nights, at least in recent memory.

Grounded firmly in American soil, The Promise of Liberty: A Passover Haggada by Stuart Halpern and Jacob Kupietzky (Maggid Books) inserts into the Haggadah text vignettes from United States history that evoke the Exodus story. Sprinkled throughout are speeches and letters from presidents, including George Washington and Abraham Lincoln—both frequently called the Moses of their eras—as well as John Adams, George W. Bush and Barack Obama, the first to bring a seder to the White House.

The history of American slavery and the Civil War are noted through abolitionist speeches and writings that reference the freed Israelite slaves. The authors also share moments from World War II, including a story about the liberation of Buchenwald on April 11, 1945. Jewish Army Chaplain Rabbi Herschel Schacter was one of the allied officers who entered the camp on that day. Among his first actions was to distribute matzah to the survivors, even though Passover had concluded a few days earlier.

The Promise of Liberty’s purpose, note the authors in their introduction, is to lay clear how the seder’s themes and imagery have been a wellspring of influence in this country, and how “the ancient Israelites’ song of Thanksgiving upon their Exodus from Egypt has long provided America with its own moral lyrics of liberty.”

A series of short essays at the end of the book from a host of prominent Jews explore sometimes little-known aspects of the American Jewish experience. Included is what may be one of Senator Joe Lieberman’s last essays before his passing on March 27. The former Connecticut lawmaker connects his participation in the civil rights movement as a young man to the Haggadah’s decree that “this year we are slaves, next year we will be free”—explaining that the present may not be perfect, but through our dreams and activism we have hope for a better tomorrow.

The final essay from acclaimed historian Jonathan D. Sarna is a fascinating piece on the seder’s traditional concluding shout, “Next Year in Jerusalem!” He points out that before the 1940s, American-made Haggadot largely omitted the phrase—or did not translate it into English—because “nobody wanted to provide fodder for antisemites or arouse suspicion of Jewish disloyalty” by implying that Jews would prefer to leave their homes in the United States, the Brandeis professor writes. That taboo was shattered completely in the Haggadah disseminated to members of the Armed Forces that had been printed during World War II and given to Jewish soldiers on the front. Written by Tamar de Sola Pool, eighth national president of Hadassah, and her husband David de Sola Pool, rabbi of New York City’s Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, the text included “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “Hatikvah,” the national anthem of Israel, and ended the seder with “Next Year in Jerusalem!” This World War II Haggadah, writes Sarna, emphasizes that “fighting for liberty and freedom” as Americans and “rebuilding a secure Jewish state in the Land of Israel are thoroughly compatible goals.”

Another positive lesson on Zionism grounds The Chinitz Zion Haggadah: How to Teach the Love of Israel at Your Seder by Marvin Aaron Chinitz (Gefen), written Dr. Marvin Aaron Chinitz. In it, he calls for the inclusion of Israel at the seder at this time of growing disengagement from Zionism among younger Americans.

In his opening, Dr. Chinitz claims that the Jewish homeland has been largely missing, even redacted, from the traditional text. Mention of a return to Israel was too dangerous or unimaginable during centuries of bitter exile, he explains. This Haggadah strives to correct that historical omission.

“The seder is the most celebrated event on the Jewish calendar,” writes Dr. Chinitz in the introduction, “and it is time to transform the connections of our seder from the story of God and the Israelites to the story of God and modern Israel.”

The Chinitz Zion Haggadah’s seder starts with “Hatikvah” and prayers for the State of Israel and the Israel Defense Forces. He also recommends placing the flag of Israel near the table and, representing the hostages taken by Hamas who are unable to be at their own seder, adding one empty seat.

Much of the Haggadah was written and compiled over the course of two years, well before the Hamas terror attack on October 7. An afterword addresses the grief, fears and need for togetherness. And in his own show of unity, after the attack, Dr. Chinitz, a gastroenterologist from New Rochelle, N.Y., volunteered for one month at Hadassah Hospital Ein Kerem, filling in for doctors called up to the reserves or mourning the loss of loved ones.

Dr. Chinitz structures his Haggadah by merging seminal moments and figures from Israeli history with the traditional text. He highlights heroes such as the IDF’s first general, Brooklyn-born Mickey Marcus, a graduate of West Point who secretly delivered supplies to a besieged Jerusalem in 1948, and Judy Feld Carr of Toronto, who was instrumental in ransoming some 3,000 Jews imprisoned in Syrian and bringing them to Israel.

The final 30 pages of The Chinitz Zion Haggadah is a succinct guide to 13 Israel-related subjects and reflections. Among the topics are the IDF’s code of conduct; the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement and the accusation that Israel is guilty of apartheid; the West Bank/Judaea and Samaria; the two-state solution; Israel’s nation-state law; and the limits of acceptable criticism of Israel.

For this final section, Dr. Chinitz advocates assigning “homework” to seder participants (he suggests a reprieve for those immersed in cooking and cleaning). He looks to teenagers and young adults to research and lead dialogue around these topics, as, he feels, “controversial discussions are usually more civilized when young adults lead the presentation.”

While some may disagree with that particular assessment, the need for this call to action and engagement with the Jewish state is indisputable.

“I am at the Seder, but my heart is in October” reads the opening text of Seder Interrupted: A Post-October 7 Haggadah Supplement edited by Ora Horn Prouser, Academy of Jewish Religion CEO and academic dean, and Rabbi Menachem Creditor, scholar-in-residence at UJA-Federation of New York. The phrase is taken from an expression by 11th-century Spanish Jewish poet Judah Halevi—”My heart is in the East but I am in the furthermost West.”

Halevi was expressing his dismay at his distance from the land of his ancient ancestors, and the editors of Seder Interrupted relate. “Many of us in the Diaspora feel the emotional connection to Israel, as well as the physical distance, as much as ever,” they write. “We are here, but our hearts are there. We are at the seder, but our hearts are still in shiv’ah be-October”—a term that can be translated as the 7th of October or the shiva mourning period of October.

How to gather and celebrate just seven months after the atrocities is the question many of the essayists, poets and illustrators in this supplement grapple with. Meant to be read before or alongside a family’s usual Haggadah, each section comments on a different part of the classic text, bringing to the table both hopeful thoughts and broken hearts, those who are determined to chart a path for peace and prosperity and those who feel that the only response to the tragedy is a prayer for mercy and intervention.

For Yachatz—the dividing of the matzah—Rabbi Matthew Goldstone, a professor at the Academy of Jewish Religion, asks how to contend with the divisions in our community and even within our own selves over responses to both the Israel-Hamas war and antisemitism. He concludes that even our ancestors weren’t certain what path to take in moments of conflict and crisis.

Rabbi Eliezer Diamond, a Talmud professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary, comments on the “Avadim Hayinu” (once we were slaves) text by noting that our own history can seem like a litany of catastrophe and horror, but that “the Haggadah is urging us to hang on. To be part of the Jewish people is to learn to keep the faith even in the worst moments….”

An essay from Hadassah’s education and advocacy division asks that another matzah be added to the typical three, which traditionally symbolize different groups of Jews. A fourth matzah would symbolize refuah—healing—a great coming together, not just at the seder but every day. Just as Jews came together in the shared grief and trauma of October 7, the essay notes, let “the matzah of refuah bring healing, joy, hope, comfort, and renewal to all those celebrating Pesach around the world.”

Amen.

Other New Haggadot of Note

The Heroes Haggadah: Lead the Way to Freedom by Rabbi Kerry Olitzky and Rabbi Deborah Bodin Cohen (Behrman House)

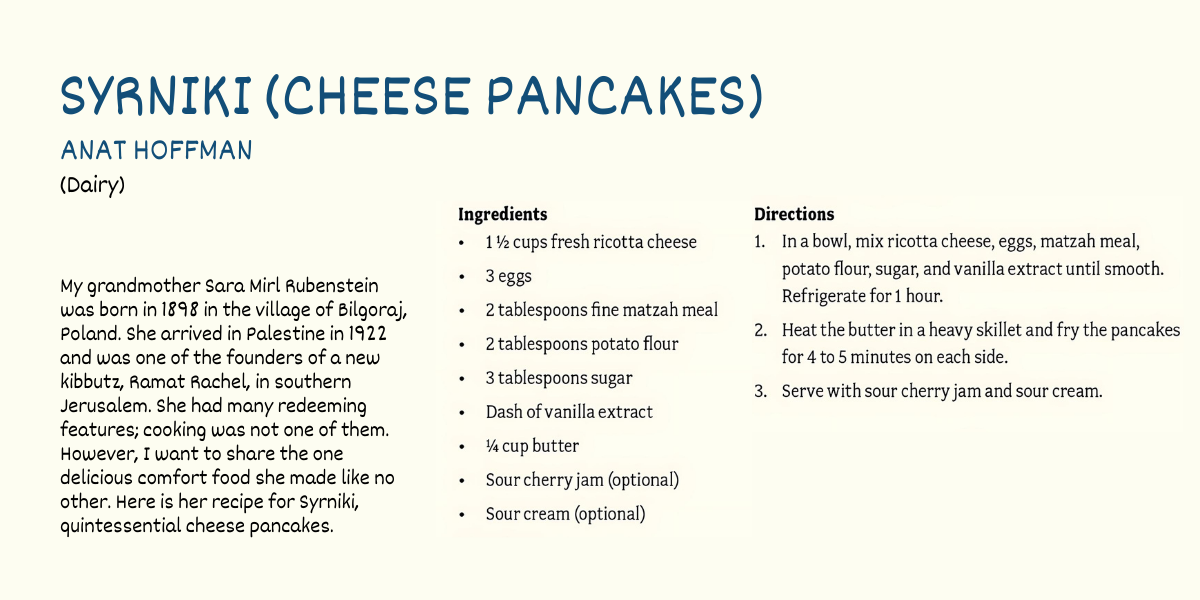

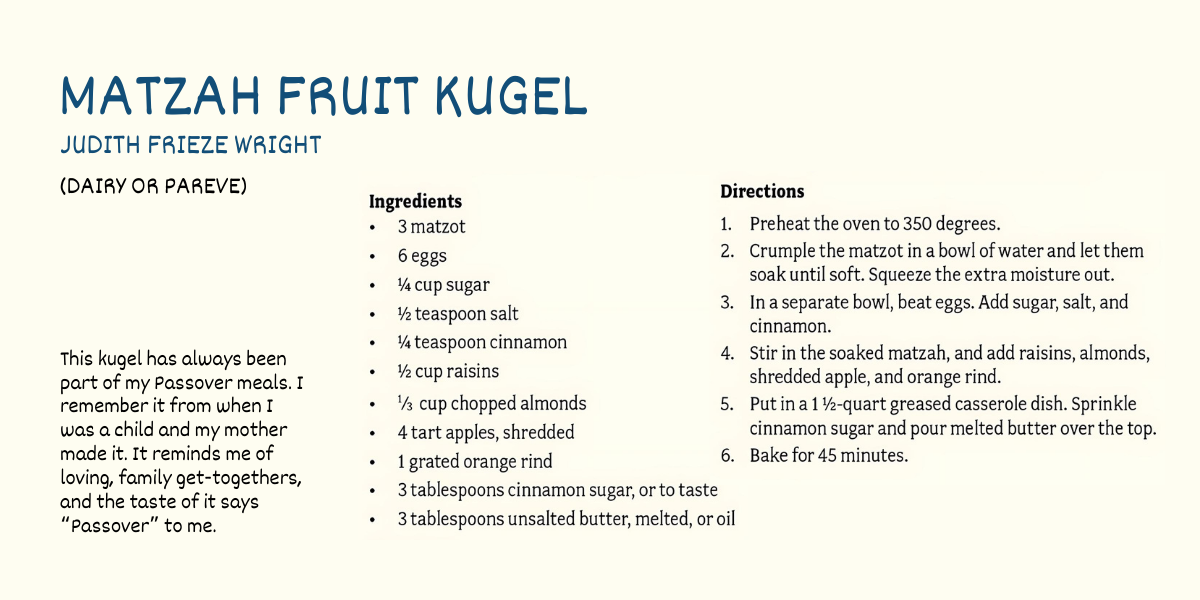

The abbreviated family-friendly Haggadah introduces readers to an array of contemporary heroes in brief essays, bringing singer Debbie Friedman into the discussion of the Exodus and comedian Groucho Marx into the section on the four children. An array of cooks from across the Jewish cultural landscape share recipes for Ugandan Charoset (from the Abayudaya community); West African Brisket (from Black and Jewish cookbook author and culinary historian Michael Twitty); Matzah Fruit Kugel (from 1960s civil rights activist Judith Frieze Wright); and Syrniki—cheese pancakes (from Anat Hoffman, an Israeli woman’s right activist and one of the founder of Women at the Wall).

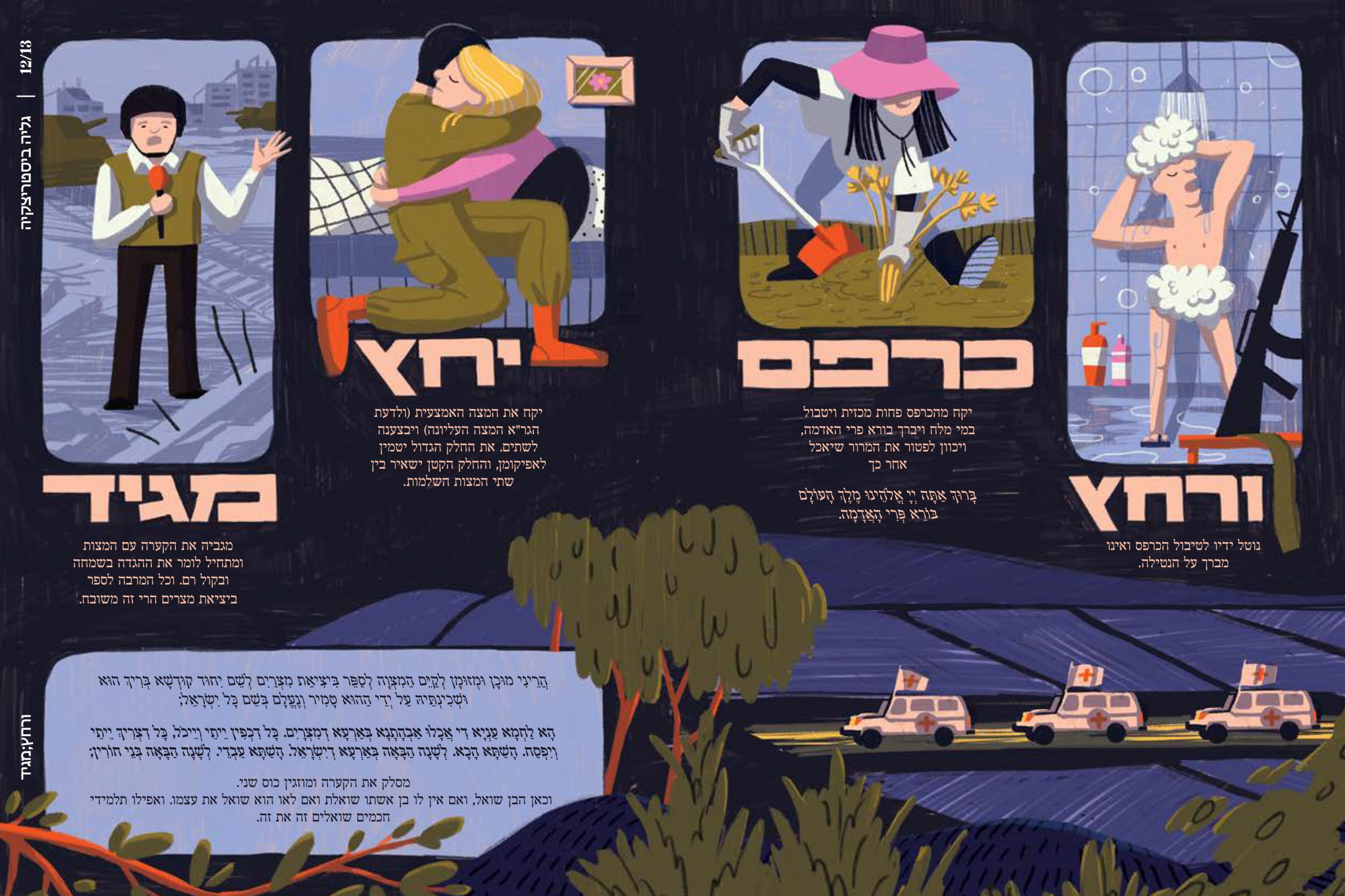

Every year, the Tel Aviv-based Asufa Israeli design collective puts together a new illustrated Haggadah to showcase the work of its members. Colorful, imaginative and often whimsical, the illustrators featured most years use their artwork to reflect on the events of the past year. This year’s Hebrew-only Haggadah is no exception. For Yachatz—the breaking of the matzah—there is an image of a mother hugging her soldier son. Maggid—the section that recounts the Passover story—features an image of a war correspondent clothed in a helmet and bulletproof vest.

Passover Recipes From The Heroes Haggadah

Syrniki (Cheese Pancakes)

Matzah Fruit Kugel

Greek Charoset

Uganda Charoset

Leah Finkelshteyn is senior editor of Hadassah Magazine.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply