American View

The ABCs of Holocaust Education

As high school teacher Becky Henderson-Howie writes the word “Dehumanization” on the chalkboard, 10 students sit quietly behind their desks, arranged in a U, and watch her with wary anticipation.

“Their initial reaction to the topic of dehumanization is usually mixed,” Henderson-Howie said, noting that the word is a discussion prompt on how the Nazis, who came to power through elections, stripped Jewish people of their humanity through words and actions.

“As we progress through the lesson, students are visibly moved by the content. Some years they pepper me with questions; some years they are very quiet and introspective,” she said. “Usually there is at least one student who is in utter disbelief.”

This particular lesson of the course, she added, is “not an enjoyable class for me.”

Henderson-Howie teaches the Holocaust as an elective for juniors and seniors at Colton-Pierrepoint Central School, a pre-K through grade 12 school that fits under one roof in a small town in the Adirondack foothills in upstate New York. Colton, which skews White, Catholic and Republican, has offered an in-depth elective on the Holocaust for the past 22 years. While the Holocaust course is optional, all Colton students in eighth grade read Sylvia Perlmutter’s memoir Yellow Star, which recounts her experience in the Lodz Ghetto in Poland as a young girl.

Since 1985, when California became the first state to require Holocaust education, mandates about teaching the Holocaust have brought the subject to American public schools like Colton.

However, where, how and at which ages the subject is taught differ wildly throughout the country; nearly half the states do not require it in their curricula at all. With skyrocketing antisemitism over the past several years, especially since the October 7 attack on Israel and the ensuing Israel-Hamas war, educators, lawmakers and Jewish institutions are reassessing the scope, focus and effectiveness of Holocaust education in helping combat the rise in Jew-hatred.

Typically introduced in secondary school, when it is taught at all, either in social studies or in English class, educators interviewed for this story say the Holocaust is discussed for two essential reasons. The first is that it is one of the seminal events of the 20th century. The second is that lessons on the Holocaust are seen as a way to teach a host of concepts, including tolerance, human rights, the effects of propaganda and discrimination and how post-Holocaust genocides, such as in Rwanda, can still happen. In short, the goal is for students to learn about the past so they may better understand the present and prevent disaster in the future.

Yet despite the efforts at Colton and other schools, a 2020 survey conducted by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany showed that 63 percent of Americans between the ages of 18 and 39 didn’t know that six million Jews were murdered during World War II; 10 percent denied it happened; and 11 percent said they believe Jews caused the Holocaust.

The widespread lack of knowledge and misinformation might also help explain why a vast majority of American adults want to see more Holocaust education nationwide, according to data recently released by the American Jewish Committee. The AJC’s State of Antisemitism in America 2023 Report notes that 85 percent of American adults want public schools to invest more resources in teaching age-appropriate lessons about the Holocaust for all students; 81 percent want statewide assessments on how effectively public schools are teaching the Holocaust; and 75 percent want state and local governments to include contemporary antisemitism in public school curricula.

As the AJC points out, each of these items echoes steps outlined by the Biden administration’s National Strategy to Counter Antisemitism, introduced in May 2023, which includes strengthening education on antisemitism, Jewish history and the Holocaust in particular.

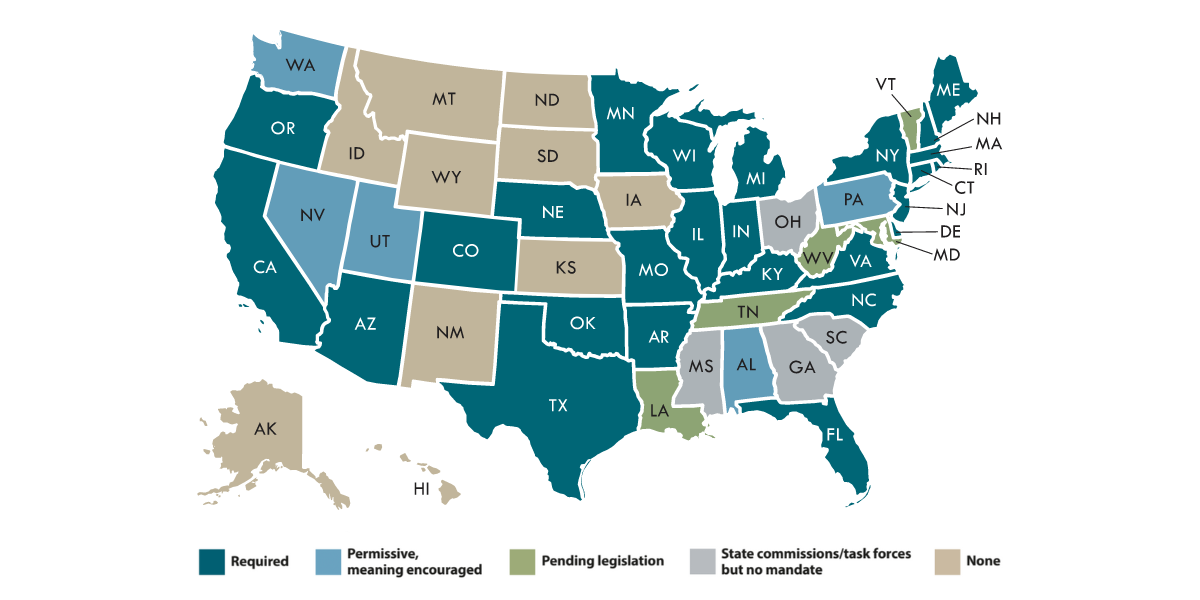

Only 27 states currently mandate some Holocaust education, largely in middle or high school, according to Echoes & Reflections, a partnership program of the Anti-Defamation League, the USC Shoah Foundation and Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial and museum in Jerusalem. The partnership provides professional development and Holocaust education resources to secondary school educators in the United States. Online lesson plans include specifics such as what life was like in a ghetto and why antisemitism didn’t end after the Holocaust.

Five states have “permissive statutes,” meaning it’s strongly recommended but not required; some states have pending legislation or fact-finding commissions; and 10 have no legislation about Holocaust education at all.

There is no national Holocaust education mandate because state boards of education decide their own curriculum, Jennifer Goss, program manager for Echoes & Reflections, explained.

The reasons why some states don’t mandate it vary, say those involved in the field. It can be due to a lack of funding or prioritizing other subjects, such as math and science-related STEM courses. There also does not appear to be a definitive correlation between a state’s Jewish population and its focus on Holocaust education, though the 10 states with no requirement do have relatively small Jewish populations.

Even when Holocaust education is mandated, the way it is taught can vary not just between states but also between schools in different districts within the same state. Some teachers include it during a broader unit on World War II when they discuss the liberation of the concentration camps by Allied forces. Others teach it as an independent unit, exploring, for example, pre-World War II Jewish life through photographs and primary source documents or the American response to the threats of Nazism through news reports and primary source documents.

Some educators teach it through fictional retellings such as Broken Strings by Eric Walters and Kathy Kacer or the graphic novel I Survived the Nazi Invasion, 1944 by Lauren Tarshis and illustrated by Álvaro Sarraseca. Others have students read first-hand accounts like Anne Frank, the Diary of a Young Girl.

In some places with mandates, teachers may opt to meet the requirements with materials that aren’t even related to Jews and the Holocaust. Teaching about genocide broadly—like the Cambodian genocide from 1975 to 1979 or the 1994 Rwandan genocide—can sometimes fulfill requirements.

However it’s taught, most educators interviewed agree that focusing solely on the number of murdered Jewish people or thenames of the concentration camps isn’t enough. To have value, they say, lesson plans should explore how antisemitism drove the Holocaust, that Jew-hatred is a gateway to wider racism and that it can threaten democracy writ large.

“If you’re teaching the Holocaust effectively, you need to teach about antisemitism,” said Goss. “You have to teach about the magnitude of antisemitism and why we should be so concerned about it today.”

This represents a change in thinking in recent years.

“We have seen a shift especially over the past decade, as now more programs that we support have developed new curricula to educate on modern manifestations of hatred against the Jewish people, including anti-Zionism,” said Becca Stern Wenger, director of the American office of the Seed the Dream Foundation, a philanthropic foundation that includes Holocaust education as one of its central areas of support.

The strongest educational materials address antisemitism as a distinct hatred, Wenger said, unique in that it manifests and morphs to target Jews wherever they live and whatever their beliefs.

A decade ago, the threat of antisemitism in the United States was not as pronounced as it is today. But that has dramatically changed over the past several years, and even more so during the past several months.

Between October 7, the date of the Hamas massacre in Israel, and December 7, antisemitic incidents in the United States reached the highest number during any two-month period since the ADL began tracking them in 1979. In that period, the watchdog group recorded a total of 2,031 incidents, including 905 rallies that included antisemitic rhetoric, support for terror against the Jewish state and/or calls for the elimination of Israel. They counted 465 incidents during the same period in 2022.

This spike in Jew-hatred is why legislators like Democratic Representative Ritchie Torres of New York said there is a moral urgency to expand education about what he called the “gravest moral catastrophe of the 20th century.”

“The lack of antisemitism awareness has social and political implications in general, including leading to the erasure of Jews as a minority,” Torres, who represents the South Bronx, said, adding that he sees a direct connection between Holocaust education and antisemitism awareness.

A product of New York City public schools, in a state where Holocaust education was first mandated in 1996, the congressman, who began serving in 2021, said he didn’t seriously engage with the Holocaust until he visited Israel in 2015 as a member of the New York City Council. Describing his visit to Yad Vashem as life-altering, Torres in December co-sponsored the Holocaust Education and Antisemitism Lessons (HEAL) Act.

The legislation would direct the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) to study and report back to Congress on Holocaust education efforts nationwide to determine where it is or isn’t part of public school curricula as well as identify the standards, requirements and instructional material currently being used.

Also in December, lawmakers in both the United States Senate and House of Representatives introduced the bipartisan Never Again Education Reauthorization Act. The act would reauthorize the legislation, which originally passed in 2020 with Hadassah as a lead lobbyist and which dedicated a fund to the USHMM to provide teachers and parents with accurate, relevant and accessible resources to improve awareness of the Holocaust.

Holocaust Education State by State

Formal Holocaust education of any sort in the United States didn’t take hold until the late 1970s and early 1980s, when courses on the topic began to be offered at universities, according to Menachem Rosensaft, a legal expert on genocide and the son of two Holocaust survivors who has served at the USHMM in Washington in various capacities.

In the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, “the only ones who spoke about it were the survivors with their families,” Rosensaft said. “Then came the publication of Anne Frank, the Diary of a Young Girl, and the novel The Wall” by John Hersey, in 1947 and 1950, respectively, followed by the 1956 publication of Elie Wiesel’s Night. These books created some nationwide recognition of what had happened to Jews during World War II.

“That was it. Maybe there was a little blip around the Eichmann trial to learn more,” he said, referring to the 1961 trial in Israel of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi official who was a key figure in the “Final Solution.”

The first states with mandates were California (1985), Illinois (1990), and Florida and New Jersey (both 1994).

Even where it’s not required, there are educators introducing their students to the subject. In 2022-2023, for example, 10 teachers in Montana, a state with no mandate, participated in a professional development program run by The Ninth Candle, a nonprofit seeking to improve Holocaust education nationally.

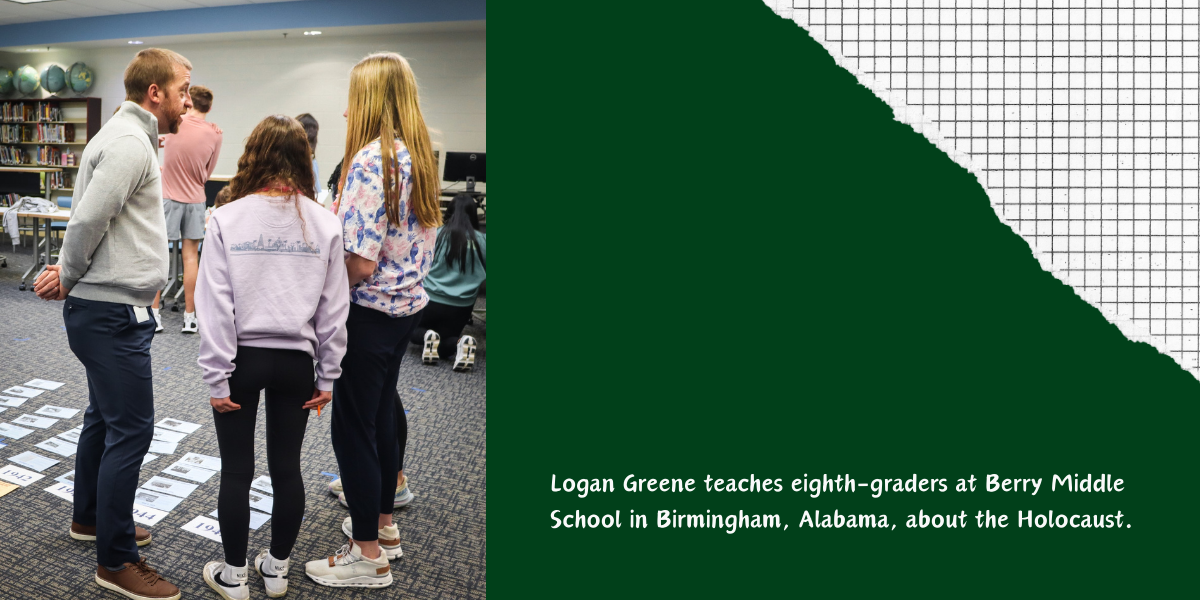

And in Alabama, one of the “permissive” states that encourages but does not require it, some teachers are bringing the topic into their classrooms.

Logan Greene, a social studies teacher at Berry Middle School in Birmingham whose student body is 40 percent minority and 28 percent economically disadvantaged, has taught about the Holocaust for more than a decade, both to high school and middle school students.

In his unit, which lasts several weeks, “I always start by asking students what they know about it. Most know Hitler. Most know about Anne Frank, although she is falling away from the zeitgeist,” he said, adding that he favors using primary sources and the USHMM’s podcast Voices on Antisemitism, which features various notable figures like the retired NBA star Ray Allen and the author Michael Chabon discussing antisemitism.

Greene’s passion for teaching about the Holocaust began in college when he read Holocaust survivor Marion Blumenthal Lazan’s memoir Four Perfect Pebbles. Years later, already teaching the Holocaust at his school, Logan learned that Lazan often conducted in-school visits. Knowing the value of hearing survivor testimonies firsthand, Greene wanted her to speak to his class. However, he needed to raise $1,000 for the speaking fee in less than two weeks.

“I told my students it was impossible,” Greene said. Five of his students decided otherwise. They stood outside of the school’s basketball games and asked people to donate $1; they raised over $1,500 in two weeks.

“Marion came, and the students had a chance to eat lunch with her. It personalized the history,” he said.

In January, Greene received the Robert I. Goldman Award for Excellence in Holocaust Education from the Jewish Foundation for the Righteous for what the group called “his outstanding commitment to teaching the Holocaust in his school.”

Greene is hopeful that Alabama will pass a mandate, though it is uncertain when or if that might happen. “A mandate would give validity and support to teachers,” he said. “It would give credence to teachers when we want to do a workshop or invite a speaker like Marion.”

As dedicated as teachers like Greene and Colton’s Henderson-Howie are, questions remain about whether Holocaust education reduces antisemitism and Holocaust denial. It’s impossible to know if those who underestimate the death toll or don’t know that Hitler came to power through elections are simply uninformed due to the lack of a cohesive or widespread Holocaust pedagogy or if they are deniers harboring deep-seated antisemitic views, Echoes & Reflection’s Goss said.

She also acknowledged that “a lot of educators wonder if they are making a difference,” even as they invite speakers, share USC Shoah Foundation survivor testimonies or take their students to visit a Holocaust museum in-person or virtually.

But Goss points to a March 2023 ADL Center for Antisemitism Research study that showed that, when properly taught, Holocaust education makes a difference.

In the study, which surveyed students who had been exposed to different kinds of Holocaust curricula, 90 percent of those who were taught about the Holocaust better recognized antisemitism’s dangers, said they would stand up for those who are being discriminated against and were more likely to challenge incorrect or biased information.

In contrast, the ADL report found that those who knew little about Jews, Judaism and Jewish history were more inclined to believe anti-Jewish tropes. For instance, those respondents minimized the number of Jews who died in the Holocaust to three million and overestimated the number of Jews to more than 21 percent of the American population. In reality, Jews make up a mere 2.4 percent.

Certainly, knowing someone who is Jewish, hearing survivor testimony or visiting a Holocaust museum increases one’s knowledge about the Holocaust. Yet, according to a 2022 Pew Research Center survey, only 29 percent of Americans have visited such a museum.

But while in-person visits to museums are valuable, they aren’t essential, according to Gretchen Skidmore, director of Education Initiatives at the USHMM. Teachers can avail themselves of free resources from the museum, including virtual professional development training, guidelines and access to primary sources. Such sources include frayed diary pages, black-and-white period footage, images of artwork collected and crafted in the ghettos and concentration camps and newspaper articles.

Numerous other museums in the country also provide curricula, including New York City’s Museum of Jewish Heritage-A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center and the Holocaust Museum Houston.

Despite promising reports linking knowledge of the Holocaust and attitudes about antisemitism, quantitative data is needed, particularly since disinformation and denial are rising, Skidmore said.

To that end, the USHMM is planning to launch the first-ever United States-based Holocaust education research center in late 2024 or early 2025, Skidmore said.

The center, also included in the administration’s antisemitism strategy, will undertake rigorous and actionable research into teaching and learning about the Holocaust and study its impact and effectiveness in the United States, she said.

Funds from the Never Again Education Act will help support the initial efforts of the research center, and its ongoing work will be supported through museum public and private funds, Skidmore added.

That research could include looking to someone like Alexandra LaShomb, who said that when she first heard six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust as a junior in high school, she was stunned.

“When you hear numbers that big you can’t understand it,” said LaShomb, who grew up in Colton and attended Colton Pierrepoint Central School.

Now a college senior majoring in homeland security at SUNY Canton, LaShomb opted to take Henderson-Howie’s Holocaust course at Colton twice. She first took it as a junior, but because of Covid-19, it was on Zoom, so she repeated the course her senior year.

“I wasn’t entirely focused. I felt like it was my duty to learn more about something so serious,” she said. “I wanted to give it the full attention I thought it deserved.”

At the end of her senior year, the class traveled to Washington to visit the USHMM. Of everything LaShomb saw that day—archival footage, propaganda posters and faded yellow stars—she said it was the shoes that hit hardest, referring to the exhibit of nearly 4,000 victims’ shoes.

“Your stomach drops. We all wake up and put our shoes on. We take them off at the end of the day. And here are the piles of shoes of people who could never put them on again,” she said. “I don’t feel like I can ever learn all there is to know about the Holocaust, but it’s so important to study. I’ll talk to people who don’t know about it, who don’t even know when World War II took place. That baffles me.”

It’s students like LaShomb who show why Holocaust education must continue to be taught in more schools, said Rosensaft, the legal expert and founding chair of the International Network of Children of Jewish Holocaust Survivors.

“Studying the Holocaust demonstrates how far hatred and bigotry can go if allowed to go unchecked,” he said. “However, legitimate Holocaust education does not begin in the gas chamber or the ghetto. Students need to understand that it begins with words and discrimination and ideology. Holocaust education is not just important. It’s critical.”

Cathryn J. Prince is a freelance journalist and author whose most recent book is Queen of the Mountaineers: The Trailblazing Life of Fanny Bullock Workman.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Ruth Bergman, Director of Education says

We are encouraged by the national attention Holocaust education is receiving at a time of rising antisemitism for Jews around the world. Old tropes resurfacing remind us that antisemitism did not begin or end with the rise of Nazism. The world’s oldest hate, baked into Western civilization, must be uprooted in our modern age.

As the nexus for Holocaust education in the State of Michigan, The Zekelman Holocaust Center has been providing age-appropriate materials, resources and instruction to eighth through twelfth graders and their teachers for nearly a decade. Often, these students are empowered to educate their parents and their communities about what they have learned. Additionally, our adult education programs reach all sectors of society, including business and corporate, medical, legal, police, and municipal staff and elected officials.

The results are heartening. Whether they work in the for-profit or nonprofit sector, adult program participants report levels of introspection and reflection that help them build more inclusive and tolerant communities. As one military professional told us, even in an organization where conformity is necessary for functioning, “I have learned to keep my humanity and personal values within the framework in which I serve.”

More formally, our internal data aligns with national findings about the long-term effects of Holocaust education on shaping positive attitudes. Visitors leave our museum empowered to challenge intolerant behavior and make a difference in their communities. As one visitor said, “Treat everyone fairly, and connect with everyone. Speak up when something doesn’t seem right.”

We welcome multi-state partnerships to expand access to resources for students and adults. No one episode of history alone can change society, but taken together, we can build a better tomorrow.