Books

Feature

Henrietta Szold’s Gifts

Thousands of people escorted Henrietta Szold to her final resting place on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem on February 14, 1945. Chilling rain and drizzle, broken only by occasional rays of sunshine, drenched the mourners as they made their way from Mount Scopus, where the bier of the founder of Hadassah had been viewed at the Nurses’ Training School she formed years earlier.

As her body was lowered into the ground, the rain became heavy, as though the heavens themselves wept, one woman recalled. A 15-year-old boy, Shimon Kritz, one of the Polish Jewish children rescued by Youth Aliyah, tearfully recited the Kaddish prayer, and the body in its white shroud was covered with earth.

Kritz and many other children in Youth Aliyah called Szold “mother.” She had headed the organization, which saved thousands of Jewish children from Hitler’s inferno and found homes for them in British Mandate Palestine.

Born in Baltimore in 1860, the eldest of five living daughters of Rabbi Benjamin and Sophie Szold, this woman, who never married or had children, became known as a mother in Israel. In her honor, Mother’s Day in Israel was celebrated for many years on the anniversary of her death. (It is now celebrated as Family Day and takes place on a different date.)

Words she wrote in a letter to her friend Jessie Sampter, “I should have had children, many children,” have often been cited to demonstrate the sorrow she felt at not having sons or daughters of her own. Indeed, she did experience an emptiness in her life due to not having built a family and she derived great pleasure from mothering the Youth Aliyah youngsters.

That phrase in her letter to Sampter was followed by the words, “It is only in rearing children that minute service after minute service counts. In my life, details have…not gone to make a harmonious and productive whole.”

Szold was a brilliant administrator. Her mastery of detail and “minute service after minute service” led to many achievements. Among them was a night school she created and ran in Baltimore to teach English to new immigrants, which would become a model for such schools throughout the United States. And, of course, there was the formation of Hadassah, the most influential women’s Zionist organization in the world. On behalf of Hadassah, she helped create and then direct a medical unit in British Mandate Palestine that over time would grow into the Hadassah Medical Organization. Decades after she founded the nursing school in Jerusalem, it was renamed in her honor.

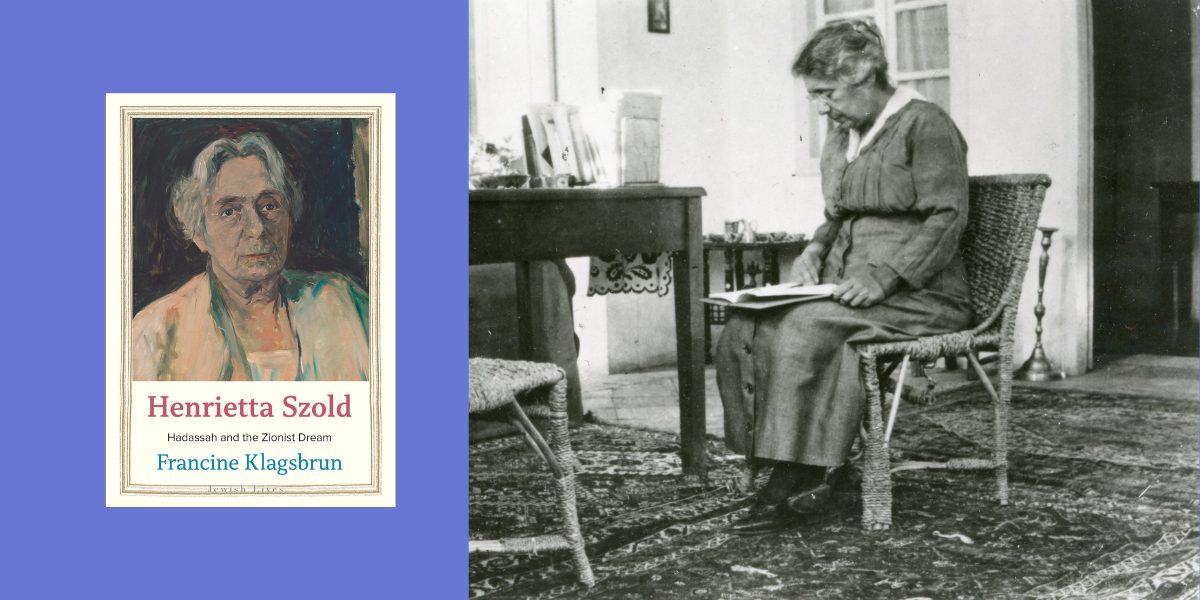

VIRTUAL EVENT: Join us on Thursday, March 21 at 7 PM ET when Hadassah Magazine Executive Editor Lisa Hostein interviews writer Francine Klagsbrun about Henrietta Szold: Hadassah and the Zionist Dream, her new biography about Hadassah’s pioneering founder and one of the most important figures in American Jewish history. Anyone who registers for this free virtual event will automatically be entered to win one of three free copies of Klagsbrun’s new book. Winners will be announced live during the virtual event.

Yet she always questioned the value of her administrative ability. On some level, she felt unfulfilled, not by a loss of motherhood as such, but by—in her estimation—a lack of creativity. She regarded Sampter, a poet, as creative, and her own extraordinary organizational talent as stemming from the narrow demands of duty. That was the true source of her sorrow: Her inability to fully appreciate the greatness of the gift she possessed.

Paradoxically, insecure as she felt about her skills, she trusted her own instincts more than she trusted others’. She had a will of iron, and she used that will to put into effect programs and projects as she believed they should be done, in spite of disagreements. For example, she was offended when David Ben-Gurion made Youth Aliyah part of the Jewish Agency, convinced that her way of handling youth immigration had been correct with no need for further input. And, in fact, she took control of the rescue of Polish Jewish children.

Modest as she was—she was indeed modest, routinely deflecting praise of herself—on occasion she allowed herself to acknowledge the uniqueness of her achievements. When she consented to direct social services for the Vaad Leumi, the National Council, which was among the governing bodies for the Jewish community in Mandate Palestine, she told friends of her “temerity” in handling such a patchwork of programs with little background in any of them. “When I came to Palestine, I acted as though I were an expert on medical affairs. Fate made me pretend to be an expert on educational affairs in 1927,” she wrote to fellow Zionist and civic leader Alice Selisberg, who became the second national president of Hadassah.

Recognizing her accomplishments in other fields, she was able to enter a new one even as she questioned her qualifications.

She had the same double vision about power. If asked, she would certainly deny that she had any power at all. She hated politics, she said, and claimed she knew nothing about government, speaking of herself as too ignorant to take a political stand on anything. Nevertheless, she wielded enormous political power, both in America and Mandate Palestine. As founder and head of Hadassah, she guided that organization to areas she cared about—medicine, education, social services and, later, rescuing children —and raised millions of dollars to support those fields.

She provided the backbone for the Hadassah women to stand up to male Zionist groups and maintain their independence. She also saw to it that Hadassah’s services applied equally to all factions: Jews, Christians and Muslims alike. While she would never admit to the power she had, she lent her name to political manifestos in the Yishuv—the pre-state Jewish community in Palestine—because she knew it carried weight. And she pushed two Zionist giants, Chaim Weizmann and Judah Magnes, to reconcile in spite of serious disagreements about the nature of the future state. Weizmann supported efforts to create a political Jewish state; Magnes was committed to pacifism and Arab and Jewish binationalism.

Zionism governed Szold’s life. At a time when many German Jewish community leaders in America rejected the Zionist ideal out of fear that Jews would be accused of dual loyalty, Szold spoke freely of Zionism as crucial to Judaism and an expression of the finest Jewish impulses. But Zionism to her also meant finding a way to live with the Arabs who inhabited the same land. She blamed the British for Arab rebellions, accusing the British of having gained their mandate by force and then not governing well. She criticized the Arabs for their violence, for not acknowledging that the Jews had a right to their homeland, maintaining that there was room enough for both peoples in the land. But she also faulted the Jews for looking down on the Arabs, and not acknowledging their national aspirations.

Her solution to the tensions, to a great extent, was to form a binational state governed by both peoples equally. But by backing binationalism, she, like the scholar Martin Buber and other supporters, was on the wrong side of history. With millions of European Jews being massacred during the Holocaust and refugees wandering about with no safe place to go, leaders of the Yishuv saw a dire need for an independent state with unlimited Jewish immigration. Had Szold lived long enough to witness Israel’s creation, perhaps she would have changed her thinking about binationalism. But her warnings about the dangers of not making peace with the Arabs in the land were perceptive. That elusive peace has remained one of Israel’s most pressing problems.

Although Szold lived out her life in Mandate Palestine, she always saw herself as an American, always on the verge of returning to the United States and her family. She wrote to her sisters every week, followed their activities assiduously and often suffered aching loneliness away from them. She visited yet she didn’t go back to live permanently in America. She spoke of her activities in Mandate Palestine as simply fulfilling her duty, but one suspects that despite her longing for her family, America no longer gave meaning to her life. She had found her soul in Palestine through the critical work she did there.

- Henrietta Szold was named in honor of Henriette Herz, an 18th-century scholar who ran a literary salon in Berlin.

- One of her earliest memories was being held up high by her father to catch sight of the funeral cortege of Abraham Lincoln.

- She had a lifelong love of botany, even delivering talks and papers on the subject, and could name many exotic plants and flowers.

- A Zionist since her early years and a fiery orator, she took pride in the fact that she gave a public talk on Zionism a month before Theodor Herzl published his first tract on the topic.

- The Jewish Theological Seminary, then an all-male rabbinical school, accepted her as a full-time student—on condition that she not pursue a rabbinic degree.

- Over the course of her life, she received hundreds of letters and answered each of them personally, often by hand.

One question remains: Does Henrietta Szold have a place in the pantheon of leaders who advanced the position of women? To be sure, on a personal level her life evolved from an acceptance of the traditional role of women in the home to striking out on her own as a single woman in a decidedly man’s world, heading major public and private institutions in America and Palestine. But unlike a feminist activist like Betty Friedan, for example, who sparked the women’s movement with its demands for equal work and pay, Szold did not initiate broad-scale struggles for women’s rights.

She did something else, however, that created its own ripples. Under her guidance Hadassah became the largest volunteer women’s organization in America as well as the largest Zionist group in the world. The growth and the status that accompanied it opened the way for women to assume roles they had never tackled before. Homemakers gained notice as public speakers; full-time mothers shone as fiscal experts; women from all walks of life developed expertise in administration, writing, fundraising and parliamentary procedure.

Through their activities, they changed the public perception of what women could do. Their daughters and granddaughters, who would argue for equal pay for equal work, learned by example from the volunteer labor of women who came before them to speak out with confidence and pursue their feminist agendas fearlessly.

Szold may not have triggered large movements, but she had an impact on thousands of women’s lives. So, yes, she belongs in that pantheon.

About a year before she died, Szold sat for a bust by the sculptor Batya Lishansky, instructing the artist to “make my eyes look to the future.” These words might well summarize her life. In every endeavor she headed she set her eyes on the future. In spite of insecurities and self-criticisms, she consistently looked ahead to expand her projects while making sure they were the best they could be in the present. Long after her death, her vision remains part of all that she created.

Francine Klagsbrun is the author of more than a dozen books, including the award-winning Lioness: Golda Meir and the Nation of Israel, and has written for The New York Times, The Boston Globe and Newsweek. This piece was adapted from her newly published Henrietta Szold: Hadassah and the Zionist Dream from Yale/Jewish Lives. Copyright © 2024 by Francine Klagsbrun. Published by permission.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Tammy Goldberg Simi says

My maiden name is: Tamar Sagher.

My grand father Prof. Aryeh Dostrovsky was the founder of Hadassah medical school.

He met with Herietta Szold in New York prior to officially opening of the school.

It was his most memorable moment and pride.

My father Prof Felix Sagher continued the family tradition and was the head of Hadassah Dermatology Dept for nearly twenty years. They collaborated on many medical research projects and published their successful work world wide. I am thrilled to join the discussion on March 21st. Thank you! Tammy Simi