Israeli Scene

News + Politics

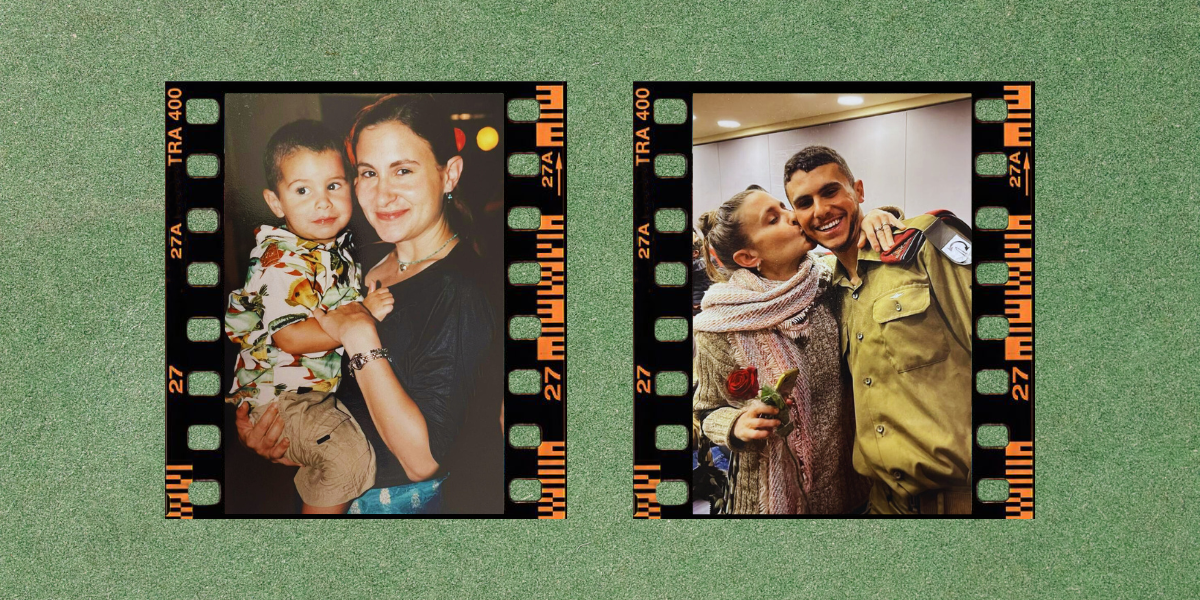

A Mother’s Phantom Pain for Her Murdered Son

Since October 10, Julie Bausi has been in pain. Her heart hurts, her uterus aches, she feels like she just gave birth.

Except that Bausi is 51 and what she’s experiencing is a phantom pain of sorts, the desperate agony of losing her son, Itai Bausi. The 22-year-old, a soldier in the elite Duvdevan commando unit, was murdered by Hamas terrorists at the Nova desert rave on October 7. It took three days for his family to receive confirmation of his death.

In some ways, the pain is in direct contrast to Bausi’s description of herself as “a lax mom.” She says she has always been fairly calm and even-tempered with her four children, especially living in the protected environment of Kibbutz Kvutzat Yavne, near Ashdod in central Israel. Bausi, a Hadassah life member who was born and raised in Queens, N.Y., would not have labeled herself a worrier.

Itai was the second of four kids born to Bausi and her husband, Shachar. The others are older sister Noa, 25, and brothers Yoav, 19, and Asaf, 15. Bausi met and married Shachar after making aliyah as a 24-year-old single and moving straight to Kvutzat Yavne.

She describes Itai as a sweet, sensitive and attentive son who had planned to travel after completing his army service in November and then raise goats with his girlfriend, Carmel, on some distant mountaintop.

“He wanted a farm,” Bausi says, a dream that solidified for Itai after his volunteer service prior to the army, when he worked with at-risk youth.

He wasn’t on duty that Saturday morning when hundreds of Hamas terrorists descended upon the music festival near Kibbutz Re’im, massacring 360 partygoers, assaulting dozens and taking at least 40 people to Gaza as hostages.

He had gone to the party with a few friends late Friday night after having Shabbat dinner at home with his family. After washing the dishes with his brothers, Itai kissed and hugged his mother, who had been out walking the family’s two dachshunds, and headed off to the party, about a 40-minute drive away.

He loved parties like that, Bausi recalls.

“He once said to me that he gets to those parties, and his girlfriend is here,” she says, pointing to one side, “and his friends are there,” pointing in the other direction, “and I’m just underneath the speaker, and I just dance.”

As the rockets began falling at 6:30 in the morning on Saturday, Itai and close friend Ben Mizrachi, a lone soldier from Vancouver who had been “adopted” by Kvutzat Yavne, got in their car and tried to head home but were blocked, like so many others, by terrorists at the exit. Their other friends had taken a different route and made it to Beersheba by 9 a.m.

When news of the attacks began filtering in, the Bausis tried to reach Itai on the phone without success. The next day, with the help of his friends who had survived, they began piecing together what happened to their son. They heard about his bravery, how Itai went back to the site of the party without any weapon or ammunition, “just some apples in his bag,” Bausi recounts. The family learned that he had helped people who had been injured, taking them to the first aid tent along with Mizrachi, who had been a medic in the Israel Defense Forces.

“They were waiting for the army to get there, trying to hold down the fort,” Bausi says.

When the terrorists closed in, Bausi learned, Itai tried to run away but was shot in the back and in his leg. He sent a voice message to his girlfriend, telling her he loved her. Having lost track of Mizrachi, he also tried to call him, but he, too, had been shot and killed; Mizrachi’s body was also discovered days later.

“We think he was alone,” Bausi says of her son’s final moments. “And for the rest of my life, I will have to imagine him bleeding to death. Bleeding to death alone.”

It’s those thoughts that traumatize Bausi, who sometimes wishes that Itai would have been killed while fighting in Gaza, surrounded by his comrades, where he would have left the world knowing that his people were helping him, trying to save him.

“That scenario of him dying alone is very, very hard for me,” Bausi says, “even more than knowing I’m never going to see him again. I couldn’t think of anything worse.

Jessica Steinberg is the arts and culture editor at The Times of Israel.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply