Being Jewish

Clinging to My Grandmother’s Afsa During War

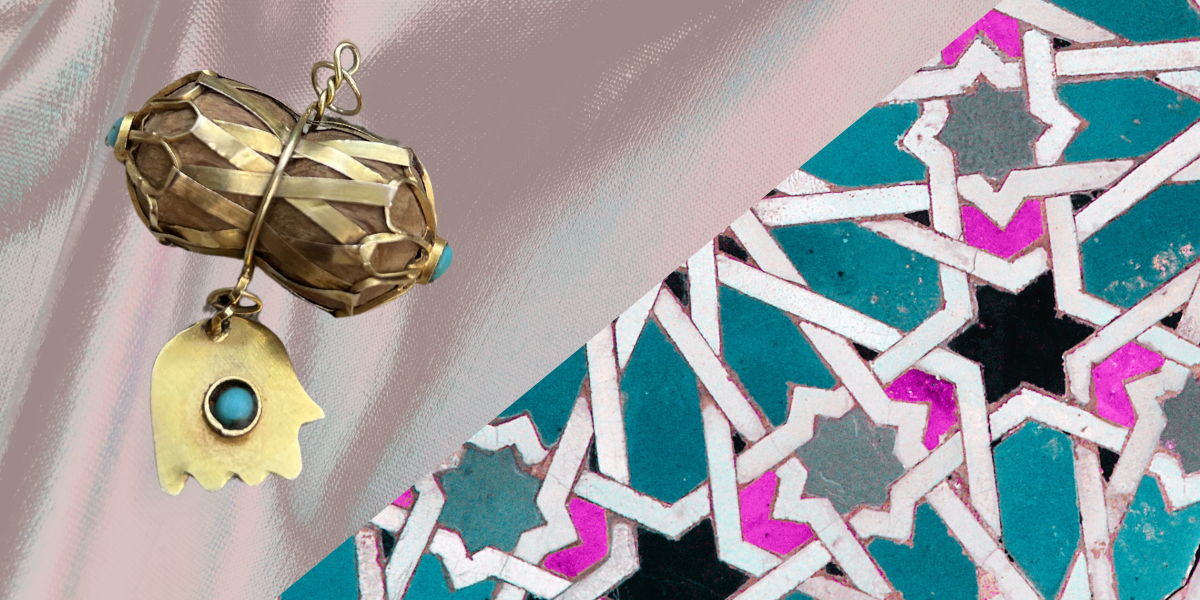

Instead of the Star of David that so many are proudly wearing nowadays, I wear an afsa on a chain around my neck. A pendant made of gold chains braided around two oak gall nuts, an afsa is an Iraqi Jewish amulet that resembles two breasts with a small hamsa placed between them. It is traditionally pinned to a newborn’s blanket by the mother for protection. My Iraqi-born paternal grandmother gifted me the afsa when my son, the eldest of my four children, was born. These days, that son is serving in the Israel Defense Forces.

These days, I cannot stop clinging to my afsa.

I think of this moment as a time of mothers, a war for mothers. It began with the merciless Hamas massacre of towns and kibbutzim in the South that spared neither women nor babies. The long hours of Hamas carnage were captured in real time on mothers’ WhatsApp groups. I saw frantic texted pleas of “help” and quick tutorials on how to lock safe rooms. Reports of grenades, shooting, the smell of burning. Questions pinged: “How do you breathe in a safe room filled with smoke?” A voice note from a mother: “My baby is dead.”

In the weeks after October 7, many mothers in Jerusalem stopped taking their children to the park, fearful of being outdoors during an air raid siren. I opened my home and backyard garden to neighborhood mothers with small children terrified by loud booms in the sky. The mothers came together in my home—some whose husbands have gone to the northern and southern fronts, some whose sons are serving and some who are grieving the murder of family members. I offered them a break in the form of tea, books for their children, art lessons and games of chess. For a couple of hours each week, it felt like we were O.K., that together we could protect our children.

I keep thinking about Kibbutz Be’eri, one of the southern kibbutzim attacked by Hamas. Founded in 1946, among its early members were a group of Iraqi Jews who walked through the desert to find a place to escape the antisemitism that had reached a tipping point with the 1941 Farhud massacre.

“Farhud” means violent dispossession in Arabic. For two days starting on June 1, 1941, during the holiday of Shavuot, over 1,000 armed Iraqis slaughtered members of the Baghdadi Jewish community. The official tally is between 150 and 180 murdered, but there is a mass grave in Baghdad that holds over 600 unidentified Jewish bodies. Over 600 were injured and many were raped. Some 1,500 Jewish homes and businesses were looted. A few days before the Farhud, Jewish homes were marked with red hamsas.

In Iraq, every Jew was suspected of being a traitor. I shudder when I hear the angry anti-Israel chants on the streets of Paris, London and New York City. They are echoes of the chants of the Farhud.

“Allahu Akbar!” (God the Almighty!)

“Idhbah Al Yahud!” (Butcher

the Jews!)

“Mal el Yahud–Halal!” (Sanction to rob the Jews!)

All four of my grandparents left Iraq in 1951. They were part of the Israeli airlift that brought some 120,000 Iraqi Jews in the mass exodus called Operation Ezra and Nehemiah. They left Baghdad so their children and grandchildren would never have to hear those chants again. It was not safe in their country. Jews were being jailed, fired from jobs, barred from universities and attacked on the streets as Zionists. Their bank accounts were frozen and their property was confiscated.

My afsa is meant to protect children. My Iraqi grandparents tried to protect me as a child from their own story. When I was young, they never told me why they fled their native country. I had to reconstruct their stories as an adult.

My paternal grandparents arrived in Israel with one suitcase for their family of seven. They were sent by the government to transit camps, called ma’abarot, which were poorly run with unsanitary conditions. In Israel, they faced discrimination as Mizrachi Jews, but at least they were safe.

From living in a tent in the transit camp, they rebuilt their lives and grew their family. Their first house was in Zichron Yaakov. Then, 16 years later, they moved to Sydney, Australia, to be with family who had moved to Australia decades earlier. That is where I grew up. In her home, my grandmother fed me kubbeh bamya, sambousek and baklava infused with cardamom. She fed me with the flavors and textures of the land that she described as the “Garden of Eden,” but would not tell me why they left. She modeled for me how to feed my children steady, wholesome meals. The kind of meals that hold you together in a war.

In keeping with Mizrachi Jewish tradition, she would light seven Shabbat candles, then more on Saturday night and more still throughout the week to dispel the darkness in the world. These days, in the Jerusalem home where I have lived since making aliyah 10 years ago with my husband and children, I cannot light enough candles.

When people protest that Israel is a white colonizing and occupying entity, I ask myself, where is my Iraqi Jewish anger? But I was not brought up to express anger. I quash it down.

Over 850,000 Jews from Arab lands were displaced in the wake of adverse reaction to Israel’s statehood. Almost all found refuge in Israel, and over half of Israel’s current Jewish population is of Mizrachi and Sephardi heritage.

There are only three Jews in Iraq today. Our prophets’ tombs and the ancient synagogues lie in ruins or have been turned into mosques. The Iraqi Jewish nakba, catastrophe, is real, but we don’t talk about the sad things.

My great aunt made that clear when I asked her about the death of my maternal grandmother’s 2-year-old son in the transit camp. “Why speak about sad things?” she told me.

The mothers in my Jerusalem garden could only whisper their fears about the October 7 pogrom above their children’s heads: It can happen here. We lock our doors now in Jerusalem. A few mothers who came to my garden lamented that half of Jerusalem does not have safe rooms. One shared that they shelter under their dining table when the sirens sound. I have a small basement safe room—safe enough—and I am happy to share my shelter with these women.

I shelter, too, under my history. Through research and writing, I am piecing together my lost 2,600-year-old Babylonian Jewish history and identity. I grew up in silence, in not speaking about sad things. I cannot stop reading and writing about my Iraqi Jewish past. I wear it around my neck.

The gall nuts that form an afsa are not actual fruit but rather a woody deformity that an oak tree produces to protect itself. It has antibiotic properties. In Iraq, it was crushed to make the ink used for writing Torah and phylactery scrolls.

My afsa represents my grandmother’s love and wisdom. It’s my history and memory. I will pass it to my son when it is his turn, insh’Allah, with God’s help, to pin it to his own child’s baby blanket.

Sarah Sassoon is an Iraqi Jewish writer, poet and educator living in Jerusalem. Her newest children’s book, This Is Not a Cholent, is set to be published in May 2024 (sarahsassoon.com).

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Nanette Jiji says

Wonderful article!

Years ago I bought one in Schunat Hativah. I would like to buy a couple more.

Do you know where I can buy them?

Cindy David Sachs says

Thank you for this lovely piece. My first grandson is about to have a bris and I was going to get the afsa to pin on a dress from India which has been passed down. I wanted a story for the afsa and this is it. I’ve used it for both my sons but my mom never mentioned why…and I never asked!

Warm regards,

Cindy from Boston