Books

‘Unearthed,’ a Yiddish Actress and a Holocaust Mystery

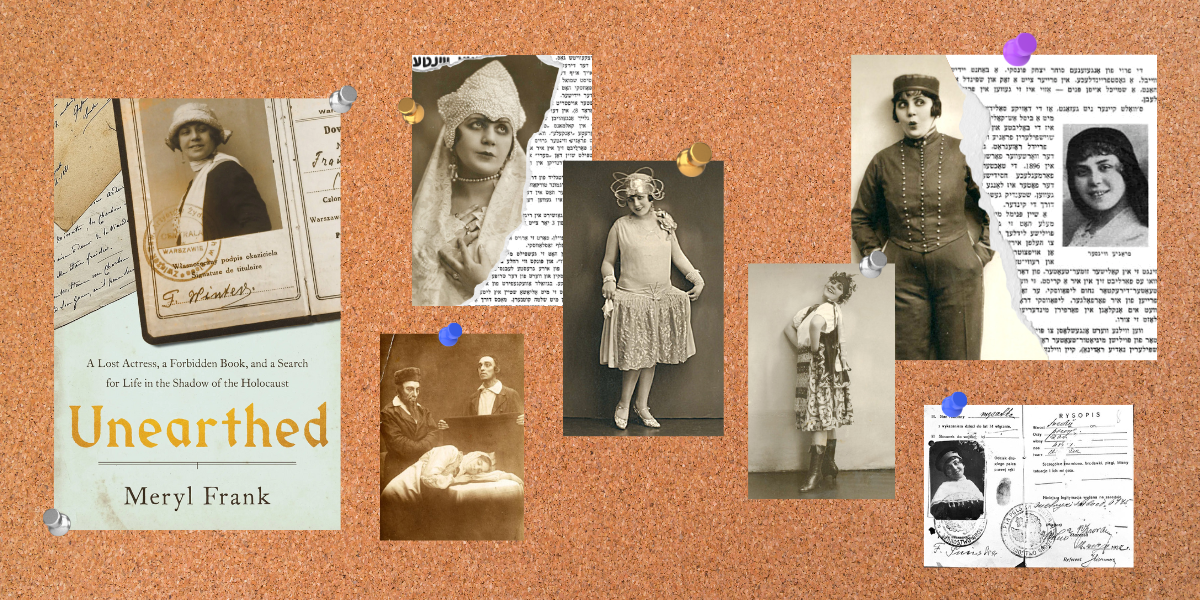

Unearthed: A Lost Actress, a Forbidden Book, and a Search for Life in the Shadow of the Holocaust

By Meryl Frank (Hachette)

“Keep it,” Aunt Mollie, an aging Holocaust survivor, said to her niece Meryl Frank about a Yiddish book titled Twenty-One and One. “Pass it on to your children. But don’t read it.”

That admonition sets the tone for Unearthed, Frank’s search for relatives lost in the Holocaust, but also for how understanding the past can help deal with today’s complex world. Frank, a former mayor of Highland Park, N.J., and a major figure in international women’s rights organizations, delivers a heavily footnoted, poignant true story of her years of deep research to determine how relatives near and far coped with unthinkable horrors.

Frank was a young mother in 1996 when her beloved aunt regaled her with stories of life in cultured pre-World War II Vilna, Lithuania (today’s Vilnius). Among the highlights of those stories were descriptions of Franya Winter, a cousin and one of the great talents of the Yiddish stage of the 1920s through 1930s.

In her family, Frank writes, the Holocaust was “everything and nothing.” Although they rarely spoke about it, she explains, every action they took was informed by it. Frank decides to learn about her “ancestral burden” and the terrible scourges endured by some family members.

Anyone doing genealogical research meets mystery upon mystery, dead ends, coincidences, mistaken identities and, one hopes, bountiful surprises. Frank’s story is no exception. The reader travels with her as she scours libraries and gets assistance from translators and well-meaning Vilnius locals. Frank travels to Europe and Canada, where some of her family relocated, in search of relatives, several of whom appear in photographs in the book.

One Book, One Hadassah live with Unearthed author Meryl Frank

Join us on Thursday, December 21 at 7 PM ET for a live virtual discussion with women’s rights activist and author Meryl Frank about her unflinching memoir about unraveling a World War II-era family mystery, Unearthed: A Lost Actress, a Forbidden Book, and a Search for Life in the Shadow of the Holocaust. Topics also include the importance of Holocaust memory in addressing antisemitism today. A recording of the event will be available for those who register. Free and open to all.

Writing in first person and in calm, understated prose, Frank reveals rarely discussed details of the Nazi assault on the Jews of Lithuania. It was in Lithuania, she writes, rather than in Poland, where the “Germans first put their genocidal theories into practice” more than six months before Reinhard Heydrich and his SS colleagues articulated the concept of a Final Solution at the Wannsee Conference in January 1942.

The vast majority of Vilna’s Jews were not sent to death camps. They were shot dead in the forest and buried in enormous open pits. Killed, the author writes, in a “horrifyingly personal way, their murderers looking them coldly in the eye as they pulled the trigger at close range. Friends, family and neighbors looked on.”

Yet, before the war, Vilna was an unusually cosmopolitan city, whose inhabitants spoke a polyglot of Polish, Yiddish, Hebrew, Lithuanian, Russian and German. Indeed, changing geopolitical borders meant that in different eras, the city shifted between Polish, Lithuanian, Nazi Germany and Soviet Union rule.

Frank describes the vivacity and intellectual trends of pre-war Vilna, particularly its Yiddish theater. Beginning in the 1920s, the city’s theater emerged as a cultural force in Eastern Europe, performing musicals, comedies and serious plays. Maurice Schwartz, New York’s leading theater impresario, brought his hit show Yoshe Kalb to Europe in 1935 to 1936, and Winter, Frank’s cousin, was hired to join the touring company.

As Vilna was besieged by the Nazis in 1941, the university cut its admission of Jews to 8 percent of the student body—in a city that was 40 percent Jewish. In neighboring Poland, the Yiddish theater virtually disappeared.

Forced into the Vilna Ghetto, Winter and her fellow Yiddish actors concentrated on trying to stay alive. Which brings us to Twenty-One and One, a slender volume that recounted the history of the Yiddish performers in Vilna. It was only after her aunt’s death and years into her own research into her family’s history that finally Frank decided to read the book, satisfied that she had the background to understand her cousin’s story and ultimate fate—and ready for answers to a few of her questions: How long did Winter survive? How did she die? And why did Frank’s aunt forbid her from reading the book?

What Frank learns startles her and compels her to put her thoughts and experiences into Unearthed, a book that asks readers to grapple with another question. How relevant are Winter’s experiences, indeed of all victims of the Nazis, for her descendants—and for Jews today?

Stewart Kampel was a longtime editor at The New York Times.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply