Arts

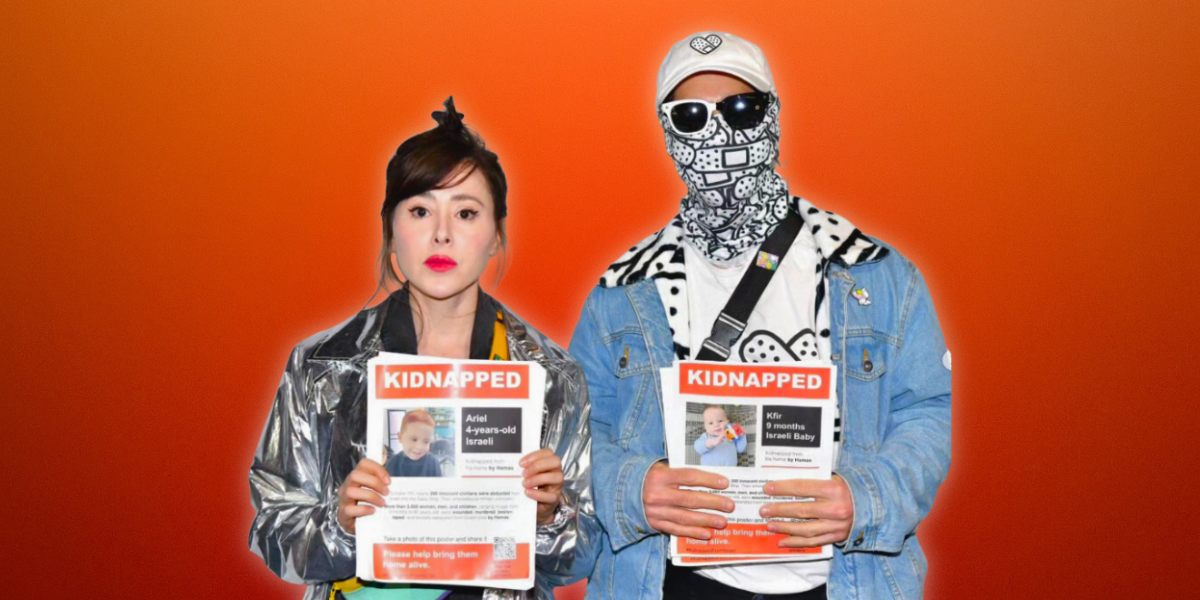

The Artists Behind the Hostage Poster Project

In the early morning hours of October 7, Israeli artists Dede Bandaid and Nitzan Mintz woke up to frantic phone calls in New York City, where they had recently arrived for a three-month artist residency. Devastated by news of the Hamas attacks that the world would soon learn killed more than 1,400 Israelis (the number is now estimated at 1,200), the couple, both in their 30s, felt agonizingly helpless. “We wrote on Facebook, ‘What can we do?’ ” recalled Mintz.

Tal Huber, a graphic designer based in Yavne, Israel, responded. The three hatched an idea: They would create posters to draw attention to the hostages held in Gaza, currently estimated at some 200.

And so a global phenomenon, “Kidnapped From Israel,” was born. If you’ve spent time in a major city recently, chances are good that you’ve seen the trio’s red-and-white posters taped onto bus shelters, trees and streetlamps. “KIDNAPPED,” each flyer announces in white-on-red block letters, along with the name, age and smiling picture of an Israeli hostage in happier times. The posters are among the most well-known public art initiatives bringing attention to the plight of the hostages.

Users have downloaded versions in 36 languages from the project’s website, kidnappedfromisrael.com, and shared them widely across social media. Printed copies have been featured at pro-Israel rallies around the globe, from Australia to Belgium, as well throughout the United States.

Just as quickly as they appeared, the posters became a flashpoint in an anguished global conversation, as sympathies shifted following Israel’s military actions in Gaza. On social media, videos circulated not only of pro-Palestinian activists tearing down posters, but also of outraged bystanders confronting those activists—often with strident and vitriolic language.

In its #ReleaseTheHostagesNow campaign, Creative Community for Peace, an entertainment-industry alliance dedicated to combating antisemitism and cultural boycotts of Israel, showcased “Kidnapped from Israel.” The initiative has garnered support from many celebrities, including Chelsea Handler, Michael Douglas and Debra Messing. All three have featured the posters on their social media accounts and Messing has shared images of herself putting up printed out copies.

The arresting mix of high-impact graphics, text and trauma was on-brand for Mintz and Bandaid, Tel Aviv natives who first connected through the city’s street art scene. Bandaid—a name he adopted in tribute to his signature motif—works in a Pop-Art style and is known for his outdoor murals and other works, including the temporary installation of a nearly 100-foot bandage on the helicopter landing pad at Hadassah Hospital Ein Kerem. He chose the Band-Aid as his symbol after finishing his Israeli military service in 2005, during the Second Intifada. Painting bandages expressed his complicated feelings about his service, he said, and he found the motif to be cathartic, not only for himself, but to his many fans as well.

Mintz, who refers to herself as a “visual poet,” caught Bandaid’s attention when she began scrawling her own poetry on walls next to his art in Tel Aviv. Now partners in life as well as in art, they now frequently collaborate and exhibit internationally.

In late October, the pair spoke to Hadassah Magazine about “Kidnapped,” what it felt like to see the project go viral as well as the art-world’s backlash against Israel. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Tell us about your initial concept for the “Kidnapped” project?

Mintz: We decided to go with the aesthetic of those classic milk cartons with the missing kids. You see first the white letters, ‘kidnapped,’ on a red background. And then the face is really big. Those are the two things that attract the eye.

I printed 2,000 copies and we went across Manhattan and hung posters everywhere we could. We approached strangers on the street, asking them to put them in their neighborhoods to help us. And nobody agreed, you know? Nobody.

How did that make you feel?

Mintz: The loneliest people on the planet. Like, this is the end of Israel. We’re all going to die, and nobody will blink.

We cried. But before we went to bed that night, we said, at least let us put the files on a Dropbox and share the link in our social media.

And in the morning, when we woke up, we discovered that the entire city of Manhattan was covered with posters.

Bandaid: We were amazed to see how it spread. In two days, it was already all over the world. And the reactions…. We wake up every morning with new surprises.

Who was your intended audience, and what did you hope to accomplish?

Mintz: Everybody. Our main goal is to reach the decision makers—the politicians that can actually bring pressure on this negotiation. We want the hostages back so deeply.

Your posters have been hung—and also torn down—around the world. How do you feel about the reactions to your project?

Mintz: The turning point happened when Israel was wrongly accused of bombing the hospital in Gaza. That’s exactly the moment that hell broke, all the anger and antisemitism. It’s trendy on TikTok and Instagram to take down the posters; it’s a global phenomenon now.

What do you make of the muted response to the murder of Israelis by the art world, including condemnations of Israel’s response to the attacks by Hamas in articles and letters in leading publications such as Artforum?

Mintz: I wish it was just pure silence. But it’s the opposite of silence. They attack, they blame, they judge. This is really shaking up the entire art world.

But I’m not surprised. I’m not naïve. I never thought the art world is built from saints. People can be really stupid. Why wouldn’t artists be stupid? Who are they? Are they God?

How has this project changed your approach to art?

Bandaid: Everything else just doesn’t feel important. We can’t find the time to make art. But even if I had time now, I can’t look at my art as something that’s important to do.

People are still joining our project, pushing it forward. They take the posters down; we put them up. It gives the project the exposure we need. We are much more than posters by now.

Hilary Danailova writes about travel, culture, politics and lifestyle for numerous publications.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

joshua burton says

The note on this article says that it was edited for content and brevity. The lovely thing about a website is that brevity doesn’t have to be a concern. I think it would be interesting to see what else these artists had to say. Please post the rest of the interview.