Books

And the Ban Played On

In 1991, as a young journalist fresh out of graduate school, I was assigned by my editor to cover an exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago. The exhibit was called “Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany.”

When I walked into the exhibit, my breath caught in my throat. Chills covered my arms as I viewed the more than 150 paintings—brilliant masterworks—that the Nazis deemed degenerate and illegal. I knew right then that I was not reporting any old story. I, the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, had found my story—the one that would forever change the course of my career.

I began a deep dive into the world of Nazi-looted art. I learned that Hitler’s first mission after assuming power in 1933 was to destroy the nation’s free thinkers—the artists, authors, journalists, architects, entertainers, philosophers and teachers who did not comply with the Aryan ideal of “acceptable” expression. As it gained power, the Third Reich executed a cultural rape and robbery throughout Europe—burning books and looting and destroying art.

I sometimes try to picture that happening to me, imagining if, as a Jew, my laptop and phone were confiscated. That peers in the writing world were arrested for working with me, and libraries were closed if they showcased my work. That anything I wrote was considered a crime against my country.

The situation in America today, of course, differs from Nazi Germany. However, across the United States, instances of, and debates about, censorship, book banning and challenges—a term, according to the American Library Association (ALA), for formal requests to remove a book from a school or library—have intensified. Caught in this web are several Jewish authors as well as books about the Holocaust.

During the 2022-2023 school year, according to PEN America, a nonprofit that works to defend free expression, there were 3,362 instances of books banned or challenged in schools and libraries nationwide, affecting 1,557 titles. This is an increase of 33 percent compared to the prior school year.

“Broad efforts to label certain books ‘harmful’ and ‘explicit’ are expanding the type of content suppressed in schools,” PEN America found, noting that topics ripe for banning include violence or abuse, race, gender and LGBTQ+ identities as well as books that discuss health and well-being, death and grief.

Censorship is fear mongering. Fear of new ideas. Fear of repercussions. The greatest underlying fear for authors like me is that our books will never be read, or we will be scared to write them in the first place for fears of the political climate or fanning the flames of culture war.

Recently, this fear blew up in our own Jewish community.

In late August, the Mandel JCC in Palm Beach Gardens, Fla., disinvited Rachel Beanland, a Jewish author, to a major event. Beanland, winner of the 2020 National Jewish Book Award for her debut novel, Florence Adler Swims Forever, had been scheduled to headline a luncheon in January 2024 to discuss her latest novel, The House Is on Fire. The book is a work of historical fiction about a deadly fire in the early 1800s in Richmond, Va., and addresses slavery and the rights of women.

In an email to Beanland, which the author shared on social media, the Mandel JCC said it was canceling the author’s appearance because the subject of her book was too “complicated…in this current political climate.”

The political climate the email is referring to is the one in Florida, where legislation has been enacted that restricts content taught in schools, calling for greater scrutiny and possible removal of books that discuss race, racism, gender and sexual identity. (Florida and Texas, both with conservative governors and state legislatures, top the list of states with the most book bans.)

Personally, I have spoken at the Mandel JCC in the past and had a wonderful experience. This decision was a shock to me and many of my colleagues. The backlash to the JCC’s decision, no surprise, went viral.

The Jewish Book Council, a national organization devoted to Jewish literature, wrote a public letter in support of Beanland, emphasizing the importance of free expression. The Mandel JCC publicly apologized to Beanland, stating this decision was not in alignment with their commitment “to promoting diverse voices, opinions and perspectives.”

In an interview, Jesse J. Rosen, president and CEO of the Mandel JCC, reiterated that his team has been “working aggressively to apologize and plot a course forward” and that his board of directors has begun “to examine our internal controls and procedures to ensure that communication from our agency is reflective of our values and what we stand for.”

The Mandel JCC reinvited the author to speak at the luncheon. Beanland respectfully declined. The damage was done, but hopefully lessons have been learned.

“As writers, we have a responsibility to tell stories that bear witness, both to the injustices of the past and today,” Beanland told me. “This is our gift: Using words to help people see the world for what it is and what it could be. I get very nervous about censorship because I don’t want a single writer to steer away from the difficult stories. It’s the difficult stories that most need to be written, devoured, discussed and shared.”

Yet “difficult” tales are being censored nationwide. And books by Jewish writers, in particular Holocaust-themed literature, are being swept up in these bans.

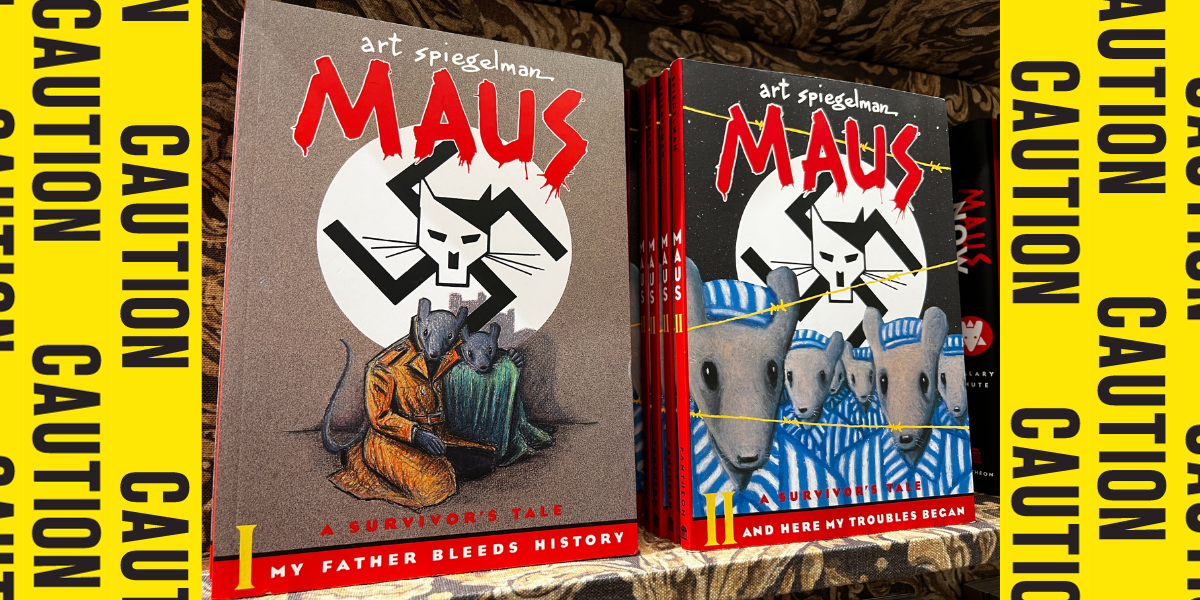

One of the more well-publicized recent instances happened in January 2022. The McMinn County Board of Education in Tennessee voted unanimously to remove Maus, Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel about the Holocaust, from its eighth-grade curriculum and school library.

The book was removed because it contained swear words and nudity, according to publicly available minutes from a school board meeting. A scene of four Jews being hanged caused one board member’s outrage.

In response to the ban, Spiegelman was quoted as noting that the censors “want a kinder, gentler Holocaust they can stand.”

Over the years, other Holocaust-themed titles have been censored. The Diary of Anne Frank, both the original diary and the graphic novel version by Ari Folman, were challenged or banned for sexual content. Lois Lowry’s Newbery Medal-winning children’s novel, Number the Stars, was challenged for language, specifically numerous uses of “damn.”

In response to the ongoing bans and challenges, in 2022, the Association of Jewish Libraries (AJL) put out a “Statement on Censorship and Banning Books,” expressing concern about the issue.

“We at the Association of Jewish Libraries are keenly aware that the banning of books is antithetical to the functioning of a healthy, free and democratic society,” Heidi Rabinowitz, member relations chair at the AJL, said in an email. “The rise in book challenges is alarming as a sign of creeping authoritarianism and an attempt to control the thinking of readers, especially young people. Jewish tradition encourages debate and the exchange of ideas, and the repression we are seeing right now is diametrically opposed to Jewish values and American values.”

A number of non-Holocaust-related books by Jewish authors have also been targeted. Among them, Jonathan Safran Foer’s 2005 novel, Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close, about a boy’s journey through New York in the aftermath of September 11, has been banned in school districts in Illinois and Ohio as well as other states for profanity, sex and descriptions of violence, according to complaints to the school boards. In 2023, 20 books by Jodi Picoult, including The Storyteller, which features a Holocaust-related plot, were pulled from library shelves in the Martin Country School District in Florida. They were among a group of 92 titles removed from that district’s middle and high schools due to a complaint filed by one parent, who claimed the works contained mature or sexual content.

Nevertheless, the majority of parents in America are against banning books. Indeed, a 2022 ALA poll notes that 70 percent of parents nationwide oppose the trend. Despite the opposition, the bans persist, as, according to a PEN America report, administrators and school boards in some states have told teachers and librarians to “err on the side of caution” about which titles to make available.

And then, of course, there’s everyone’s favorite young adult author, Judy Blume, whose books such as Forever and Deenie are frequently targeted. (Forever is among the 92 banned in Martin Country.) Blume has been a longtime anti-censorship advocate and recently became part of a group of 14 authors who raised more than $3 million to help PEN America open a base in Miami.

“I believe censorship grows out of fear, and because fear is contagious, some parents are easily swayed. Book banning satisfies their need to feel in control of their children’s lives,” she has written on a section of her website devoted to the topic. “They want to believe that if their children don’t read about it, their children won’t know about it. And if they don’t know about it, it won’t happen.”

Censorship, however, is a complex issue that spans the political spectrum. Classics like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn have faced bans or challenges by liberal groups due to racist language. And the publisher of Dr. Seuss’s books decided to discontinue several titles because of imagery that depicts racial stereotypes.

In recent years, a subset of censorship, largely associated with the left of the political spectrum, has emerged: cancellation. Many authors I have spoken with are afraid of being “canceled”—facing social media attacks, condemnation by literary groups—for writing about topics that aren’t “their own,” be it religion, race or sexual orientation.

“One of my main characters in The Stockwell Letters is a Black man,” said USA Today best-selling author Jacqueline Friedland. Before publication, she had deep concerns about the reception of her novel, which delves into the connection between Ann Phillips, an abolitionist, and Anthony Burns, a fugitive slave. “As a white woman, I certainly cannot claim any specialized knowledge about the Black experience,” she told me. “I feel strongly that it’s important for writers to try to step into the shoes of people who are different from them.”

Friedland noted that so far reception of the book has been positive. But, she added, “I worked very consciously to make sure people know that the book is as much about a white woman as it is about a Black man, which I think helped people accept the project as a whole.”

She recalled the advice that the late Toni Morrison, a Nobel laureate whose books have been targeted by bans, once gave to students at Oberlin College: “People say to write about what you know. I’m here to tell you, no one wants to read that, ’cause you don’t know anything. So, write about something you don’t know. And don’t be scared, ever.”

I am heartened by those taking action against censorship. Across the country, Banned Book Clubs are emerging, groups that are choosing restricted books to read and discuss together. In September, the Hoboken City Council in New Jersey passed a resolution that makes Hoboken a “book sanctuary”—essentially, a place that bans book bans. That same month, California passed a bill barring book bans in schools.

Jewish institutions are stepping up, too. In Missouri, during ALA’s Banned Books Week in early October, the Jewish Community Relations Council of St. Louis and the National Council of Jewish Women St. Louis unveiled a new coalition called “Right to Read.” They are partnering with several Missouri organizations to help state libraries and bookstores combat bans and challenges.

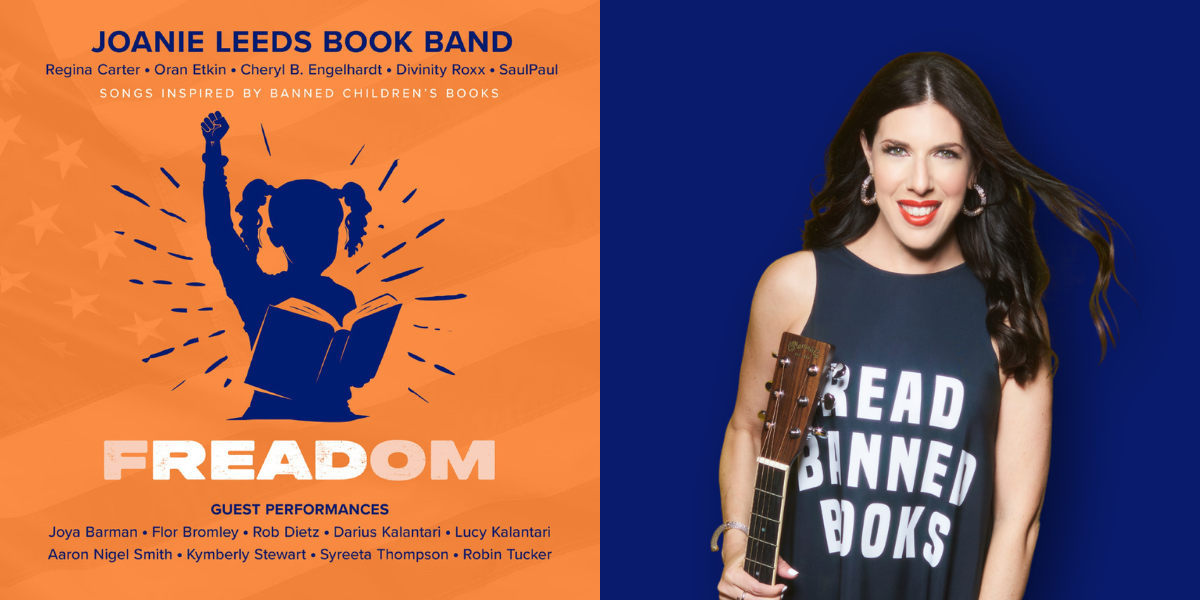

One Jewish singer-songwriter has even produced a full album dedicated to fighting bans. Grammy Award-winning singer Joanie Leeds has been making children’s music for over a decade. Her 11th album, Freadom: Songs Inspired by Banned Children’s Books, dropped in September. One song, “Cholent Time,” was inspired by Mara Rockliff’s book Chik Chak Shabbat, about a diverse group of neighbors who help an observant Jewish woman make the Shabbat stew. The book was purchased in a school district in Jacksonville, Fla., then withheld for 15 months while being reviewed by the district.

“As a proud Jewish American with strong progressive values, I’m deeply concerned about the increasing book bans across our nation,” said Leeds. “One fearful parent’s influence should not silence diverse voices in schools and libraries, violating our First Amendment rights. Sharing Jewish stories and educating non-Jewish readers about our culture are essential, just as it is for any marginalized group.”

Let children read. Let writers write. Let artists paint and sing. Let us all not be afraid to share opinions, ideas and words for fear of being banned, uninvited or canceled for creative expression. Yesterday, it was a colleague who was censored. Tomorrow, it may be me—or you. It’s time to turn the page and stand together to fight censorship and those who are trying to take a knife to our freedom of expression.

Lisa Barr is The New York Times best-selling author of Woman on Fire. Her new historical thriller, The Goddess of Warsaw, about a legendary Hollywood actress with a secret past during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, will be published in May 2024.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply