Arts

The Reopening of the National Library of Israel

A nation’s ability to define itself in writing and to transmit that definition to future generations is often considered one of the hallmarks of civilization. That, perhaps, is why the renewed National Library of Israel (NLI), which opened on October 29 in a purpose-designed building in a new location, shines so brightly within Jerusalem’s cultural constellation.

The sleek $200-million library is situated between two of the city’s most important institutions: the Knesset and the Israel Museum. Shaped like a concave lens and faced in a mix of stone and concrete that glows orange at sunset, it is far more than a building that houses books.

“It’s a place of really big questions,” said Raquel Ukeles, head of collections at the NLI. “Any time you’re dealing with collecting or curating, you’re making value judgments about what’s important. So, our primary work is to be the collective memory of the Jewish people and Israeli society. In essence, we are both documenting and, to some degree, defining what it means to be Jewish and Israeli today.”

Those interested in exploring that definition can access the Israel Collection and the Haim and Hanna Salomon Judaica Collection, two of the NLI’s four core repositories. In the Israel Collection, the NLI amasses anything related to the language and culture of the Jewish state, from every book published in the country to postcards, menus, music, photographs and internet sites. The globe-spanning treasury of Jewish texts in the Judaica collection, according to Ukeles, is larger than that in any other institution.

The other two core archives are Islam and the Middle East, considered one of the most important Islamic repositories in the region, and Humanities, which contains works from luminaries such as Sir Isaac Newton and Jewish novelist Franz Kafka.

The NLI building, which has 11 stories, five of them belowground, was designed by the Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron, whose international credits include the de Young Museum in San Francisco. The 4-acre campus is landscaped with native plants and trees that reflect themes of environmental harmony and sustainability. The plaza to the south of the building features an installation by Micha Ullman called “Letters of Light.” Inspired by the kabbalistic text Sefer Yetzirah (The Book of Creation), it features stone blocks arranged to cast shadows that form the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet.

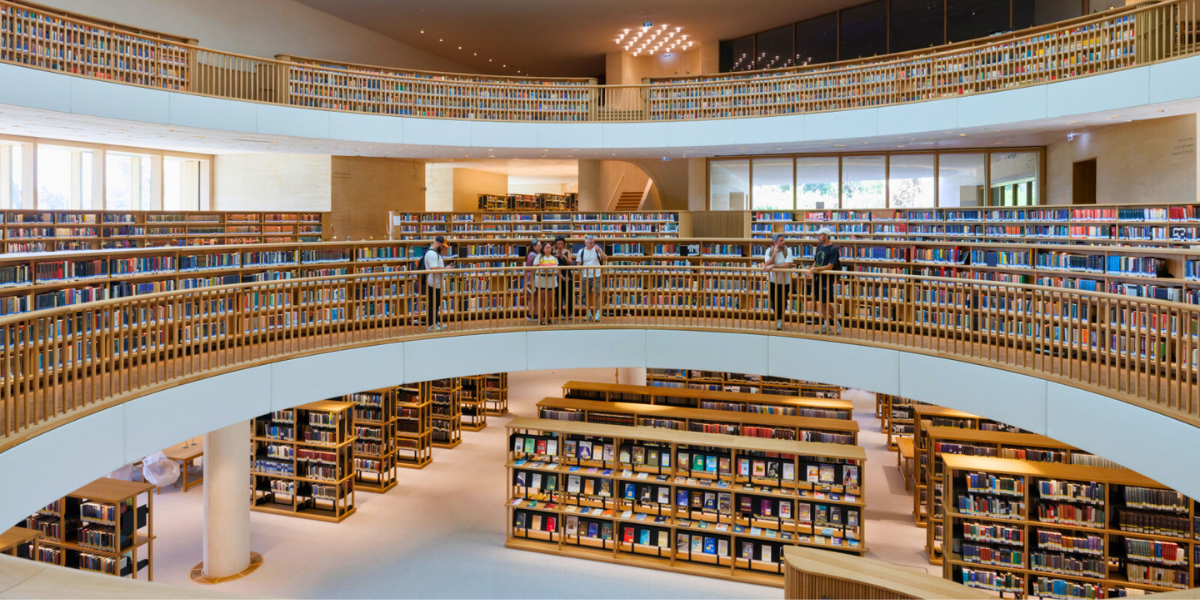

The centerpiece of the building is a three-floor circular main reading hall flooded with natural light; some —a well of knowledge with some 200,000 books lining the rounded shelves. With the building’s advanced cooling system and other green features, the NLI bills itself as the most environmentally sustainable building in Israel.

The projected 500,000 visitors annually—readers, scholars, school groups and tourists—can watch the robotic retrieval of books and view exhibitions located mainly in the wing that houses the visitor center. Among the pieces on display is a 12th-century commentary on the Mishna by Maimonides with his handwritten corrections and masterpieces from artists Marc Chagall and others. The facility also houses a synagogue with a brilliantly lit vaulted ceiling as well as a 480-seat auditorium for concerts and other events. Above all, the building’s floor-to-ceiling windows on the ground and first floors enable visitors to experience the openness of the campus.

“We wanted the building to be open and inviting,” said Oren Weinberg, the library’s director, who pointed out that the site, unlike the adjacent Knesset, is not fenced.

The seeds of the NLI were sown in 1892, when the Jerusalem branch of the B’nai Brith organization opened the city’s first free public library in rented premises on Jaffa Road. After the Hebrew University was established in 1925, the library moved to its campus on Mount Scopus. During Israel’s War of Independence, when Mount Scopus became inaccessible, the books were secretly moved to various locations. In 1960, a new home for them was built on the university’s Givat Ram campus.

Plans for the new facility were put in motion in the 1990s, when stakeholders led by the Rothschild family, members of Knesset and academics re-envisioned the library, used then mainly by scholars, as the national library of the State of Israel and of the Jewish people worldwide. In 2007, the Knesset passed the National Library of Israel Law, which defined the goals of the institution and made it independent. The groundbreaking in 2016 then led to the task of defining the four core collections.

Private funds from Yad Hanadiv-the Rothschild Foundation, the Gottesman family of New York and other donors covered 85 percent of the cost of the new building. The remainder came from the Israeli government, which will help fund operational and other costs, supplemented by grants and donations.

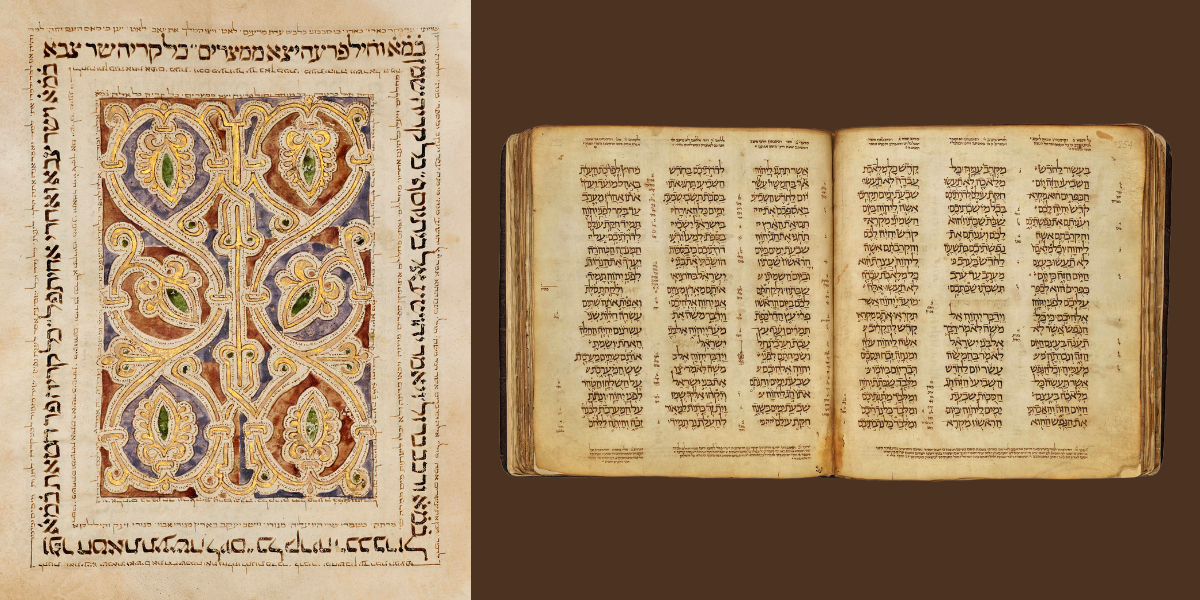

Today, the NLI houses some five million items, the vast majority of them books. Approximately 100,000 of the items are considered rare, among them illuminated manuscripts, prints from the 15th through 17th centuries, documents and religious texts from the Cairo Genizah and an extensive collection of antique maps of Jerusalem and the Holy Land. The digitization of many of the holdings, including hundreds of historical Jewish newspapers, has made them freely available worldwide.

In its former home and now in its new one, the NLI serves as a cultural center, offering lectures, films and other events, both in-person and online. Its blog shares fascinating articles in Hebrew and in English based on the library’s holdings.

Asked about the most valuable item in the library, Ukeles referenced the Keter Damascus, or the Crown of Damascus. Dating to the 10th century, it is one of the earliest copies of the Hebrew Bible in the form of a codex, or book, rather than a scroll.

But it was about another item that Ukeles told an emotion-laden story: a 400-year-old Oeiryt—the name in the ancient Ge’ez language for the Ethiopian Jewish version of the Torah. This Oeiryt (pronounced Oreet, and sometimes spelled Orit) was a very rare early copy containing the five books of Moses plus the Books of Joshua, Judges and Ruth that had been translated from Hebrew to Ge’ez. It belonged to a large family from the Tigray region of Ethiopia.

En route to Israel, the family “carried this precious text with them through Sudan,” Ukeles said. When, in 2016, they decided that it belonged in the library of the Jewish people, around 100 family members came to the museum, she said, and “opened it and…read from it. It was extraordinary. We were all crying. Since then, they come back every few years to visit their Oeiryt.”

Director Weinberg has a slightly different focus. What excites him most, beyond the NLI’s holdings, he said, are “the people who come in—the visitors, the users” and their ability to create works based on the collections.

Weinberg’s words echo a dictum from Austrian Israeli philosopher Martin Buber, whose manuscripts are among the treasures of the NLI. “After you have visited the library ten times to look at books, go once to look at the readers…,” Buber wrote. “Thus, you will be able to learn something you will probably not be able to learn as well anywhere else: Books are great, but man is greater.”

Esther Hecht is a journalist and travel writer based in Jerusalem.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply