Israeli Scene

The Jewish Traveler

Touring the Holy Land With Israeli and Palestinian Guides

When we arrived at the Artist Hotel, an airy boutique property two blocks from Tel Aviv’s Bograshov Beach, the concierge greeted my partner, Paul, and me with a warm “hello” and two breezily delivered dictums: Breakfast was from 6:30 a.m. to 10 a.m. and if air raid sirens blared, head to the bomb shelter or get as close to the ground as possible. Recent Israeli airstrikes in Gaza had “killed three terrorist leaders and some other people,” he told us. Palestinian groups had fired over 600 rockets. Oh, and happy hour was starting. Did we want wine and cheese?

A 65-year-old child of Holocaust survivors, I last visited Israel at age 17, when two friends and I picked apples on a kibbutz. Until my trip in May, I hadn’t been back for nearly 48 years. I’d returned for a seven-day “dual narrative” expedition created by MEJDI Tours that, according to its promotional literature, would be “led by an Israeli and Palestinian guide who will debate and highlight different political and historical opinions at each site.”

MEJDI Tours was founded in 2013 by Aziz Abu Sarah, a Muslim from East Jerusalem, and Scott Cooper, a Jewish social enterprise entrepreneur and businessman who lives in Chicago. The two shared a background in international conflict mediation and a desire to connect people through travel. In addition to tours in the Middle East, which also include Egypt and Turkey, MEJDI offers trips in other historically strife-ridden lands, such as Ireland and the American South.

As Paul and I sipped Shoresh Blanc from Tzora Vineyards and nibbled chunks of Tzfatit cheese, I confided to him for perhaps the 100th time since booking this trip: “I pray my parents in heaven won’t view my talking to Arabs as betrayal…. But until we see our ‘enemies’ as human beings, how can we find ways to live peacefully side by side?”

I inhaled a second glass of white wine. “I’m still haunted by my mother’s face when we watched Palestinian terrorists attack Israel’s Olympic team at the Munich Games in 1972,” I told Paul. “Israel must exist…but it’s complicated.”

The next morning, we headed to the lobby to meet the 12 other travelers in our group and two guides: Yaniv, a middle-aged peace builder who requested that his real name not be used because of what he described as the heightened political environment in Israel right now, and Alaa, a 2008 graduate of the Conflict Transformation master’s program at Eastern Mennonite University in Virginia. Paul and I instantly felt comfortable with our mostly Medicare-eligible companions, all from the United States and representing diverse heritages, including Native American, Chinese and Black.

Before boarding the bus, Yaniv, who hails from the Negev region, told us that the messages he grew up with “were to be afraid of Palestinians because Jews are always under attack. Until I was 30, I never met ‘the other’ face-to-face unless I was in uniform.”

Alaa grew up in Akko, a mixed city of Jews, Christians and Muslims, where he said he was exposed to the rhetoric of Meir Kahane. The late Orthodox rabbi and founder of the Jewish Defense League referred to Arabs as “dogs” and called for their expulsion from Israel. Alaa ultimately chose to follow the example of coexistence learned from his mother, who helped establish the Sir Charles Clore Jewish Arab Community Center, a local initiative that remains active today.

Our first stop was a short drive from the shimmering 24/7 metropolis of Tel Aviv: 4,000-year-old Jaffa. The ancient coastal city has endured many conquerors, including Canaanites, Egyptians, Israelites and the Ottomans—up through May 1948, when Israel took control after, depending on who is narrating, either the War of Independence or the Nakba (Arabic for catastrophe).

Also depending upon the narrator, Jaffa is a symbol of peaceful coexistence or emblematic of the Jewish state’s erasure of Arabs. An erasure initially due to voluntary as well as forced expulsion of Arab residents and, currently, to gentrification, with housing prices almost out of reach for many of the city’s remaining 16,000 Arabs. (The area is home to 30,000 Jews.)

The Wishing Bridge in Jaffa connects Kedumim Square, a beguiling mishmash of archeological remains, chic shops and galleries, to Peak Park. Carved into the wooden structure are bronze statues of the 12 zodiac signs. “Legend says if you stand on this bridge and touch your sign while looking at the sea your wish will come true,” Alaa said. “Not to influence you, but I wish for peace.”

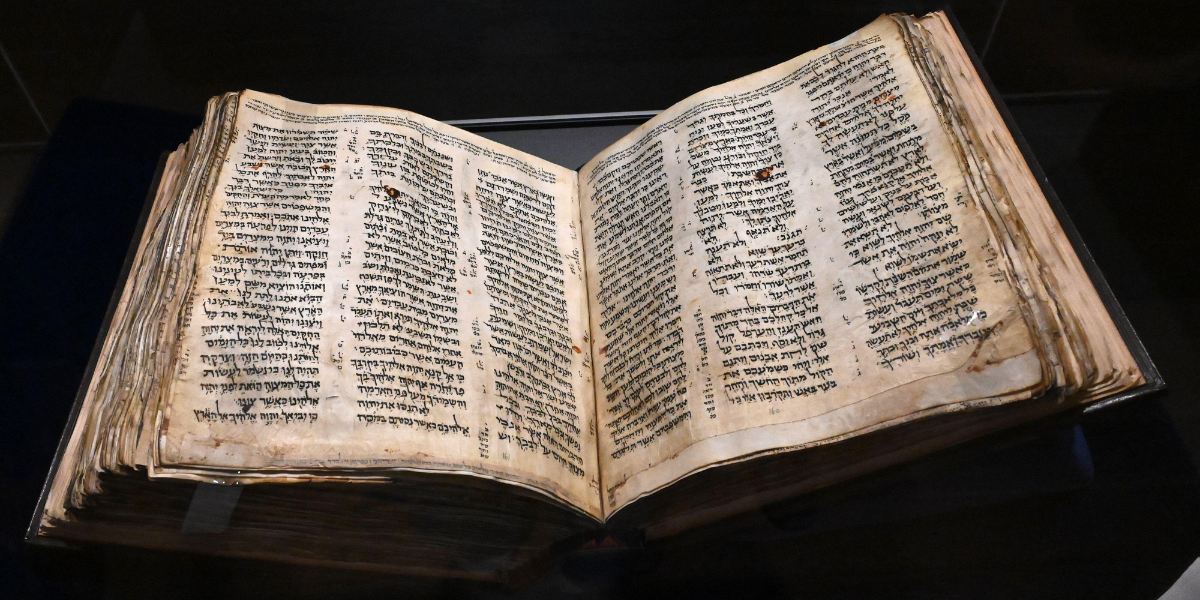

After our next stop at Tel Aviv’s ANU-Museum of the Jewish People, I experienced a swell of pride. The recently renovated and expanded institution utilizes videos, interactive stations and artifacts—ranging from the Codex Sassoon, an 1,100-year-old Hebrew Bible, to a collar worn by late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg—to showcase not just our tragedies but the sweep of Jewish accomplishments.

But my inner “yays” grew quieter during our subsequent excursion into Ramallah and Bethlehem, both located in Area A of the Palestinian Territories.

As outlined by the 1995 Oslo II Accord in what was intended to be an interim agreement, the territories are divided into sections: Area A, which is fully under Palestinian Authority control and where Israel has declared it illegal for its citizens to enter, though an exception is generally made for Israeli Arabs; Area B, in which the Palestinian Authority has administrative control, but security is overseen by Israel; and Area C, covering over 60 percent of the West Bank, where Israel maintains exclusive control.

Temporarily sans Yaniv since he cannot enter Area A, we learned that Ramallah, on the crest of the Judaean Hills, is more liberal than most large Muslim communities. Alcohol is permitted and women freely run businesses. Indeed, female chef Fidaa Abuhamdiya led us on a food tour, which was followed by a visit to a bakery managed by Arab women.

In a meeting room of Farah Locanda, an Ottoman-era house-turned-boutique hotel, our group sipped water as we listened to Samir Othman Hulileh, the chairman of the local stock exchange. Hulileh’s voice cracked as he recalled the morning in 2002 when his approximately 20-mile-drive to the factory that he owns in Bethlehem was interrupted by a call from a close friend who is an Israeli artist and army reservist.

The message: Hulileh should turn back. Israel and Hamas were clashing, and the army needed his factory as an interrogation center. “I’ll watch out for it,” his friend promised. Weeks later, the factory reopened.

“We still visit each other’s homes, but it has never been the same” since his factory was temporarily requisitioned, Hulileh told us. His conclusion? “The conflict is too strong for us to solve without a third party.”

Bethlehem is dominated by a stretch of Israel’s 25-foot-high separation wall topped in this section by watchtowers and barbed wire. Built during the Second Intifada in the early 2000s to prevent suicide bombers from entering Israel, street artist Banksy turned the wall into a tourist destination when he and his team spray-painted it with anti-war imagery—a practice since taken up by other provocateur artists.

Our group toured the multimedia museum that tells (one side of) the story of the barrier inside the nearby Walled Off Hotel, which was founded and financed by Banksy. I pressed “play” on my audio guide to hear a recorded phone message that the Israel Defense Forces typically deploy in the strategy called “roof knocking,” when they warn of an impending demolition of a civilian building. “You have five minutes to leave before we bomb,” I heard on my headset.

Back in Israel the next morning, I asked Yaniv for context about life during the fraught period between 2000 and 2005, when 887 Israeli civilians were killed in terrorist attacks. He recalled being about a dozen feet from a Tel Aviv bus that exploded. “I saw it with my own eyes,” he said. “People on it became soup. It was terrifying, unbearable.”

Our Jerusalem stops at the Kotel and Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, left me feeling viscerally connected to my parents. I felt them urging me forward.

Forward meant traveling to Gush Etzion, a bloc of 20-plus Jewish communities in Area C that is home to around 70,000 Jews. Bob Lang, head of Gush Etzion’s Religious Council, offered cookies and commentary in his home in Efrat, one of the largest Jewish cities in the area. Jews purchased land here in 1927 but were thrice driven out by Arab violence until Israel regained control in 1967 after the Six-Day War. While acknowledging that walls and barriers are not the road to peace, Lang doesn’t foresee change “while Arab leaders teach that killing Jews is a good thing.”

If Hulileh and Lang exuded varying degrees of hopelessness, our next speakers, who met with us at the Holy Land Hotel in Jerusalem, shone a flashlight beam into inky darkness. Osama Eliwat and Elie Avidor represented Combatants for Peace, a movement composed of former fighters on both sides of the conflict.

Raised in East Jerusalem, Eliwat’s first encounter with Jews was watching Israeli soldiers beat his father. At 14, he began throwing stones and hopping on rooftops to spraypaint “Free Palestine.” After twice being arrested and released by Israeli authorities, in 2010, Eliwat accompanied friends to a meeting for peace activists. There he met Israelis who, he recounted, “believed I was human and deserved rights.” It was the first time he heard about the Holocaust. “They said, ‘I hear your pain, and I have stories, too.’ “

This proved to be his turning point. He attended more meetings and came to believe that “the main source of the conflict is we don’t know each other.” He said that he decided “to dig deep, to fully understand the narrative and fears of Israeli Jews.” At age 35, this quest led to his first plane ride, to visit Auschwitz.

Avidor fought with the IDF in the Golan Heights. “It felt good,” he said of his army service. “I was protecting my family.” After the army, he lived in North America for 20 years. When he returned to his homeland, his perspective had changed. In 2016, he accompanied a friend to the annual Israeli-Palestinian Joint Memorial Day Ceremony, sponsored by Combatants for Peace and The Parents Circle, an organization of over 600 bereaved families on both sides. “For 90 minutes I cried, listening to everyone’s stories,” Avidor recalled.

“People tell me I hate Jews and love Arabs,” he said about his involvement with Combatants for Peace. But, he added, “I do this work because I love my country.”

Our group’s final evening together offered a partial answer to a question Yaniv had posed days earlier: “How do we find a way to communicate without yelling?”

In a modest home in the West Bank town of Al-Eizariya in Area C, our host Mustafa Abu Sarah—brother of MEJDI co-founder Aziz Abu Sarah—served the classic Arab chicken dish of maqluba (upside down). The entrée is so named because the pot of stewed chicken, spiced rice and vegetables is flipped onto a large serving plate.

We worked off calories by dancing to the darbuka and lute-enhanced stylings of two members of Wast El Tarik, an Israeli-Palestinian musical ensemble.

Back on the bus, our group joyously warbled through a medley of friendship-centric songs. As the last notes of “Why Can’t We Be Friends?” faded, our hotel came into view. While our lives would soon physically diverge, 14 souls had been forever transformed by a vision of what is possible.

Sherry Amatenstein is a New York based psychotherapist, author, anthologist and journalist who has written for many publications, including Tablet, New York, Better Homes and Gardens and AARP’s The Ethel.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Jo Ann Friedman says

Unfortunately I do not see peace in the future until Israel’s right to exist is acknowledged and until being a terrorist is not an exultated status.

And yes, Israel has to acknowledge that Palestinians have a right to live there as well.

sherry amatenstein says

I agree on BOTH of your points. Thank you very much for reading my article.

Sharon Weiner says

I disagree there’s a million Arab countries that didn’t want the Palestinians so they decided that they will going to take land from Israel remember the Dome of the Rock is built on two temples. The Palestinian people have a right to be part of Israel. We do not negotiate with them because they are controlled by Hamas and Hezbollah who in turn is controlled and funded and trained by Iran.

Sheldon Finkelstein says

In light of this past weekend’s events, the murder of over 700 Israelis and counting, I’d say the timing of this naive article by a New York based liberal is pretty sad timing.