Israeli Scene

When Golda Meir Pulled Off the Impossible

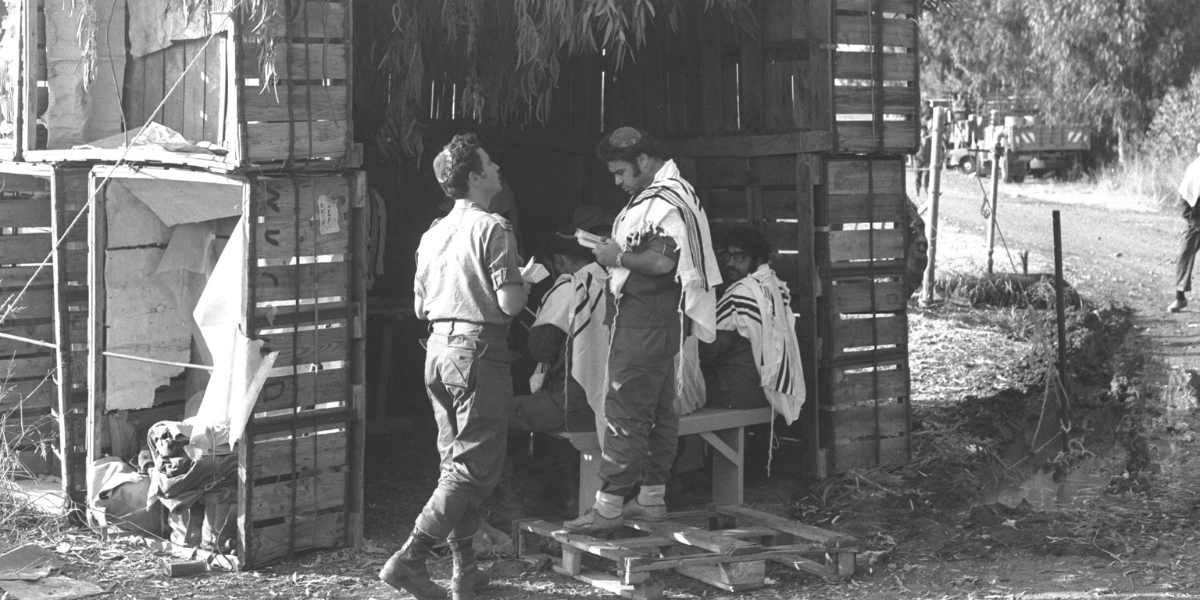

On October 6, 1973, as Israelis throughout the country marked the Yom Kippur holiday swaying in prayer, Prime Minister Golda Meir sat with her cabinet, dazed, chain-smoking and trying to comprehend what she had just been told.

The Arabs were about to attack, there were hardly any Israeli soldiers in the field to stop them, and the army could not be mobilized for another 48 hours. Golda suggested to her ministers that they convene later that day—and was cut off in mid-sentence by the wailing of sirens. She turned to her stenographer.

“What’s that?” she asked.

“It would appear the war has begun,” the woman replied.

“Nar das felt min oys,” Golda muttered in Yiddish. “This is just what my life was missing.”

Wars, Golda often said, should only be managed by people who hate them. By that measure, she more than fit the bill. But that was seemingly her only qualification. Though she was the first woman in the history of the world to rise to become a head of state without being related to any male politician or king, she was also the first—and to this day, only—Israeli prime minister to never have served in uniform or in Israel’s defense ministry. She believed her generals when they told her there would be no war. She believed them when they told her there was no need to mobilize the army.

Fortunately for the Jewish state, she proved a quick study. The massive intelligence failure resulted in the war beginning about as badly as any war could. Israel’s defensive line along the Suez Canal crumbled, while the Syrians penetrated deeply into the Golan Heights.

Worst of all were the human casualties and the massive loss of planes and tanks during the first three days of fighting. Golda was horrified to learn that at the current rate of destruction, the nation would soon succumb to the tyranny of arithmetic. Defense Minister Moshe Dayan—the very symbol of Israel’s fighting spirit—was heard to murmur that “the Third Temple is at risk.”

But Golda kept her cool. When Dayan suggested readying nuclear weapons, she looked at him dismissively and said, “Forget about it.” She then sent the last division Israel had to the Golan Heights rather than hold it back to defend against a potential attack from Jordan.

For two nerve-shattering weeks, Jerusalem sat undefended, naked to attack. Jordanian combat engineers were spotted along the Jordan River mapping potential crossing points, but King Hussein left the border quiet, as Golda had predicted. And the division sent north turned the tide of battle and pushed the Syrians back to their original lines.

In the South, Dayan advised pulling back to the more easily defensible Mitla and Gidi Passes. The move would stem the loss of men and materiel. But it meant giving up any hope of crossing the Suez Canal and defeating the Egyptians. Golda overruled Dayan and ordered the army to dig in and fight. The line held, the losses eased and the army remained within striking distance of the canal.

To the shortage of men and weaponry was added a new problem: a shortage of time.

On October 10, the Israelis learned that the Soviets, who had allied with the Arabs, were planning to propose a cease-fire in the United Nations. Golda knew that once the fighting ended, she needed bargaining chips to trade at the negotiating table. And so, in what those present described as one of the most difficult decisions of the war, she sent her battered army on a counterattack into Syria. Her generals scraped together what they could and conquered a bulge that left the outskirts of Damascus within artillery range.

The war was far from over. Egyptian President Anwar Sadat turned down the cease-fire proposal, and Golda had to decide whether to go for broke and attempt to cross the canal. An army group set loose west of the canal could potentially win the war. But Dayan cautioned in a climactic meeting on October 12 that if the attack failed and a large force was lost west of the canal, they might find themselves “fighting on the outskirts of Tel Aviv.”

With the tension as thick as the cigarette smoke blanketing the room, Golda and her generals received word from Israel’s master spy, an officer in the Egyptian army: Sadat was planning a massive offensive. When the Egyptians attacked on October 14, the Israelis were waiting for them. In one of the largest tank battles in history, the Israelis lit up the battlefield, destroying 250 tanks while losing only six.

In a head-spinning, spectacular throw of the dice, Golda then instructed her generals to cross the canal. The Israelis only had 650 tanks holding the line; they would send 400 of them across the canal. Even with all that equipment, the Egyptians still possessed a lopsided advantage in personnel and materiel.

And that was assuming the Israelis could even cross the canal. Doing so required moving a 450-ton “rolling bridge” down a narrow road defended by thousands of dug-in Egyptian troops. The man given the task of getting the army over the canal was Ariel Sharon, a swashbuckling, insubordinate general whose superiors had twice recommended relieving him of command.

Fortunately for Israel, he lasted in his job long enough to ignore his orders one last time. On this occasion, he was told to sit tight west of the canal with a small vanguard that had paddled across in rubber boats and do nothing until the rolling bridge was laid. Instead, in an unauthorized assault, he ordered his tiny force to attack north along the west bank of the canal. The Egyptians east of the canal saw the advancing Israelis through binoculars, grew alarmed that they were being surrounded, and pulled back further north to shorten their lines. The Egyptian retreat east of the canal opened the path for the rolling bridge to get through.

This is when the war entered its most dangerous phase. The Israelis crossed the canal and sped across the open expanse of the Egyptian heartland. Meanwhile, Henry Kissinger, the American secretary of state, sped just as quickly to Moscow to conclude a cease-fire proposal. The Soviets wanted to rescue their Arab allies. Now the Americans wanted a cease-fire, too.

On Cctober 20, Kissinger learned that the Arab members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries had imposed an oil embargo on the United States and other nations in retaliation for their support of Israel during the war. The CEOs of America’s oil companies informed him that while World War II rationing had reduced oil supplies to American consumers by 6 percent, the embargo threatened to reduce it by 18 percent.

The cease-fire was declared in the United Nations Security Council on October 22. Golda told her generals to ignore it and encircle the Egyptian Third Army. The Soviets were irate. Using unusually strong language, they warned ominously “of the gravest consequences” for Israel. They also hinted at sending in troops, and thereby sparked the most dangerous superpower confrontation since the Cuban Missile Crisis. Golda, a lioness in orthopedic shoes, dug in her heels and stood her ground.

The cease-fire officially went into effect on October 24. On November 1, Golda traveled to Washington to meet Kissinger for one of the most acrimonious meetings ever between an Israeli prime minister and an American secretary of state. To Golda’s protests he responded, “You’re only three million. It is not the first time in the history of the Jews that unjust things have happened.”

Talks dragged on in Washington for days, with Kissinger shuttling between the State Department, where he met with an Egyptian envoy, and the Blair House, where he met with Golda. The Egyptians were adamant that Israel had to pull back to the October 22 cease-fire line and release the grip on their Third Army. Golda refused. Israeli soldiers would stay put. They would allow supply of the Egyptian army, but only if POWs were exchanged. No withdrawal would take place without an agreement on Israel’s terms.

On November 3, Kissinger lost patience. “You will have a hell of a time,” he said, “explaining to the American people how we can have an oil shortage over the issue of your right to hold territory you took after the cease-fire.”

Washington had supplied practically all of Israel’s weapons for the war. An American air bridge had all but rescued the Jewish state. Kissinger now warned Golda that if fighting resumed, Israel could not count on further resupply. He also offered the opinion that there was “next to no chance” that the Egyptians would accept her proposal. Golda demanded that he march back to the State Department and present it anyway.

Several hours later, Kissinger notified Golda that the Egyptians had given in. The Israelis had won the Yom Kippur War. A separation agreement was concluded, one that gave Egypt a toehold on the east bank of the canal. But it forced them to pull back their surface-to-air missiles and other equipment, thereby rendering any future military adventure impossible.

The outcome of the war also forced Egypt to make a stark choice: Make peace with losing the Sinai Peninsula or make peace with Israel. Syrian President Hafez al-Assad faced a similar choice and chose to give up the Golan Heights. Sadat famously chose peace—making an historic visit to Jerusalem in 1977, signing the Camp David Accords in 1978 and concluding with the Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty in 1979. Both historic documents were signed by Sadat, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and President Jimmy Carter. In 1982, Egypt received the Sinai Peninsula.

It was this agreement that broke the ice in Israeli-Arab relations. Only after Egypt, the largest and most important of the Arab countries, accepted a Jewish state could other smaller countries follow in its wake. Jordan and, much more recently, the countries that signed onto the Abraham Accords—the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan—would never have dared to recognize Israel were it not for Camp David. And Camp David would never have happened had Israel not won the Yom Kippur War.

In short, Golda pulled off the impossible. She defied the United Nations, stared down the Soviets, steamrolled the Egyptians and outlasted the Americans. Upon leaving office, Dayan said emotionally that no Israeli prime minister had withstood outside pressure with greater fortitude than Golda.

The result spoke for itself: A nation caught almost completely off guard turned the tide of battle in less than three weeks. As for the initial intelligence failure, the postwar Agranat Commission found that Golda had “acted properly” in the days leading up to the war.

All of which leads to a painful question. Why have Israelis judged her a failure? Every time they are asked by pollsters to rank their most admired prime ministers, David Ben-Gurion, Menachem Begin and sometimes Yitzhak Rabin battle it out at the top. Golda always comes out at the bottom.

Circumstances no doubt played a part. The 1967 Six-Day War expanded Israel’s borders but it also raised expectations. The failure to achieve another easy victory and the loss of the sense of invincibility—these things were bound to take a toll.

There is a darker side as well. There were many in Israel who chose to glean from the Yom Kippur War that Israel had to trade land for peace. The way this camp saw it, Sadat wanted peace all along, and the Yom Kippur War would have been prevented had Golda accepted a land-for-peace offer in 1971. This revisionism is contradicted by the entire historical record. Sadat never made any such offer. But nothing, it seemed, could explode this myth. Not even an interview that Sadat’s widow, Jihan, gave to an Israeli newspaper in 1987 in which she said, “I don’t agree with those that say that Sadat tried to reach true peace before 1973. I believe he only wanted a cease-fire agreement, and nothing more.”

Maybe now, 50 years later, with a little more perspective—and a lot more declassified material—the true story can finally be told and Golda can take her rightful place in the pantheon of Israel’s great leaders.

Uri Kaufman spent over 20 years visiting battlefields, speaking to participants and reviewing thousands of pages of material for his book Eighteen Days in October: The Yom Kippur War and How It Created the Modern Middle East, from which this piece was adapted. Copyright © 2023 by the author and reprinted with permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

P. Bonapart says

Thank you for an outstanding article. Between Uri Kaufman’s article and Helen Mirren’s performance in the movie “Golda”, I hope that the reputations of both Golda and David “Dado” Elazar are repaired and, as Uri call for at the end of his article, they can take their rightful places in the pantheon of Israel’s great leaders.

NathanSolomon says

Can you help me locate a picture of Myself (Nathan Solomon) with Prime Minister Golda Meir whom I sat next to at the Truman Institute where the final cease fire speech was given by the PM. I was one of two students from Tel Aviv University invited to the Truman Institute to hear her speech.

P. Bonapart says

Thank you for an outstanding article. Between Uri Kaufman’s article and Helen Mirren’s performance in the movie “Golda, I hope that the reputations of both Golda and David “Dado” Elazar are repaired and, as Uri call for at the end of his article, they can take their rightful places in the pantheon of Israel’s great leaders.