Being Jewish

Rebecca Gratz as Namesake, Aunt and Inspiration

In 2020, Rebecca Gratz was newly in addiction recovery when she visited a Louisville, Ky., library with companions from her treatment program. While chatting with friends, she looked down and realized that her hand was touching a book bearing her own name. It was a volume of some of the collected letters of Rebecca Gratz, the groundbreaking 19th-century philanthropist and educator whose influential Jewish American family had funded the establishment, among other things, of Philadelphia’s Gratz College, the first independent college of Jewish studies in North America.

“The fabric of my life changed when I found those letters,” recalled Gratz. Growing up Christian in Lexington, Ky., she’d been told only that she was named for a noteworthy relative. But she knew nothing of her family’s Jewish heritage, let alone that her namesake, a great-great-great-great aunt, created the model for America’s Jewish Sunday school movement.

That serendipitous discovery of the volume imbued in Gratz a resolve to be more like her stalwart namesake: She is now three years sober, is pursuing a career in technology—and has mastered challah baking.

In June, Gratz journeyed to Philadelphia to promote the launch of the Rebecca Gratz Digital Collection, Gratz College’s online archive of letters, receipts and other documents assembled from various institutions that reveal the private life of the Jewish feminist pioneer.

Nina Warnke, the collection’s lead editor, said Gratz’s writings are distinguished by their unusual span—65 years, from adolescence into her 80s—as well as their insights into 19th-century American womanhood. Gratz’s day-to-day musings “open up a world,” Warnke said, from commentary on the latest Sir Walter Scott novel to describing the perpetual fear that women might die in childbirth.

Indeed, anxiety around health is “a persistent theme,” Warnke noted. With frequent epidemics like yellow fever, Gratz and her correspondents “talked about whether they should move to the country, reassured each other about who was safe.” Letters weren’t just a nicety, Warnke added. They were “vital communication in an era before mass media.”

Over the past year, Warnke and her colleagues have transcribed about 100 of the nearly 800 handwritten documents, thereby allowing people not only to read them but also to search the material by keywords. At the Rebecca Gratz Tea Party celebrating the collection’s debut, Warnke said she hoped to recruit volunteer transcribers to complete the project.

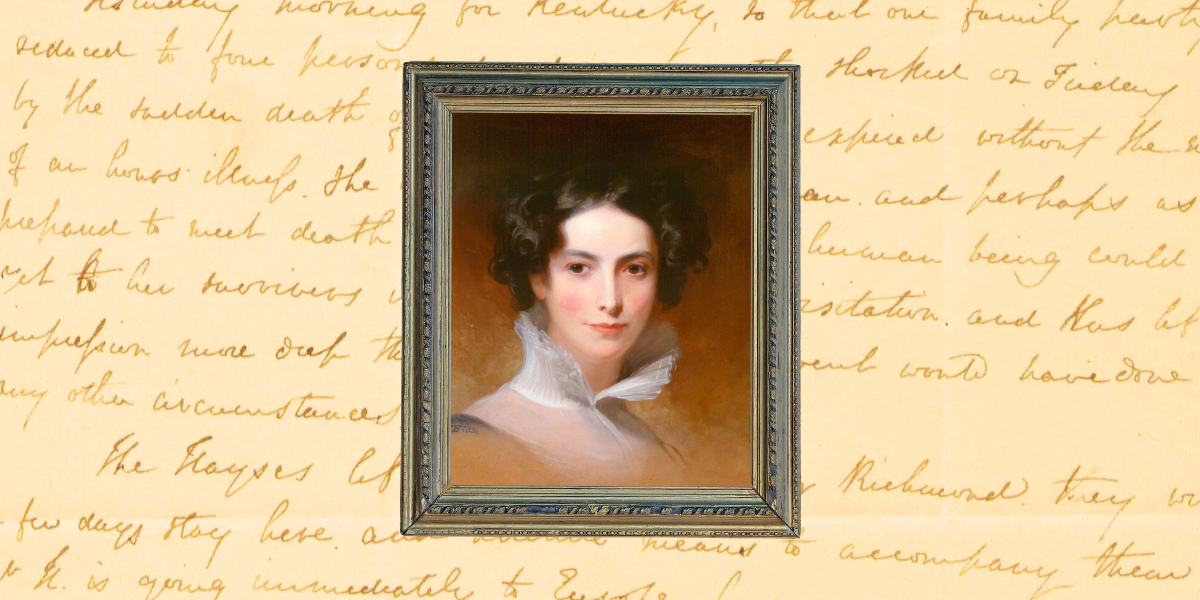

For her part, the modern-day Rebecca Gratz took a DNA test to confirm the connection before touring Gratz family sites around Philadelphia, including Mikveh Israel Synagogue, where the Gratzes worshiped, and the Rosenbach Museum, which houses a portrait of her namesake.

Moved by “the kindness, the welcome and the genius of the Jewish community,” Gratz said, “I kept thinking: ‘Rebecca, are you watching what’s going on?’ She would have been so glad that her effort and legacy are being maintained with such passion and care.”

Hilary Danailova

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply