Israeli Scene

The Genius of Golda Meir

In writing this biography of Golda Meir, I faced a serious case of historical whiplash. I read myriad works—scholarly studies, popular books, memoirs, autobiographies, biographies, plays and essays—that address the life and career of Israel’s fourth prime minister. The portraits they drew of her and her accomplishments differed markedly. Some of these works vilified and reviled her. Others valorized and revered her. When studying a person’s life—particularly a life lived so publicly—one expects to find divergent evaluations. But these ranged from the venomous to the hagiographic. I experienced the same whiplash in personal encounters when discussing her impact and legacy.

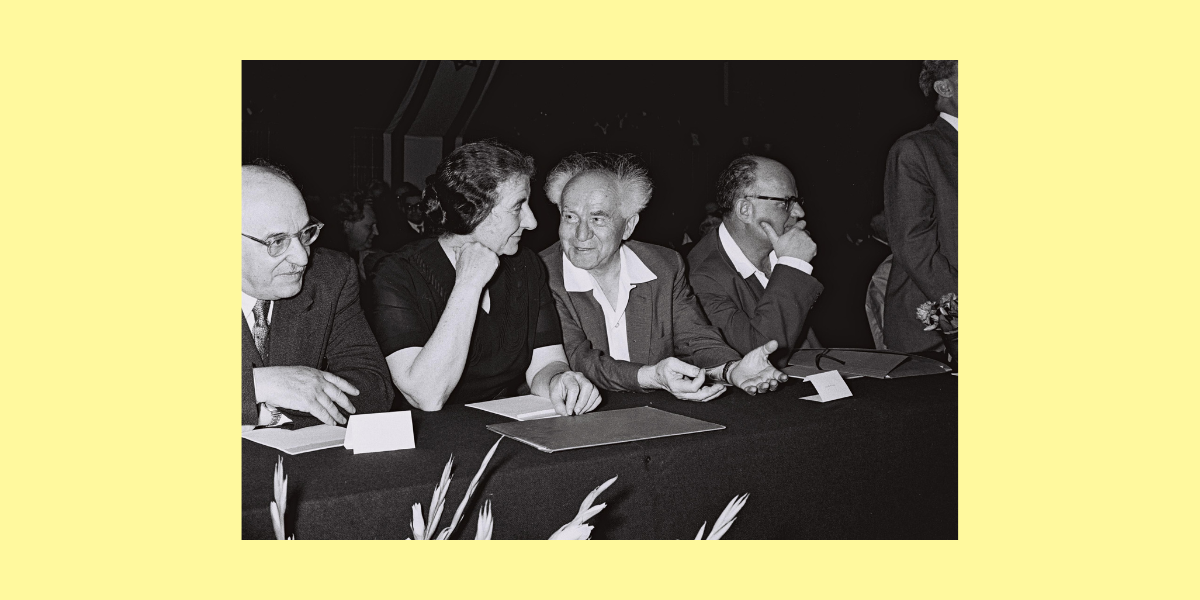

Who, then, was the real Golda Meir? She was part of the small cadre of people who helped craft the Jewish state and lead it as it transformed from a wobbly enterprise to a regional military power. She was one of only two women to sign Israel’s Declaration of Independence. She was the first and, as of now, the only woman to lead Israel.

In addition to shaping Israeli society, she, possibly more than any other Israeli with the exception of David Ben-Gurion, built and cemented the Jewish state’s relationship with the American Jewish community. American Jews were in awe of the brawny, tanned and swarthy sabras, the “new” Jews, the kibbutzniks and fighter pilots. But it was Golda who captured their hearts—and their purses—for the Zionist enterprise.

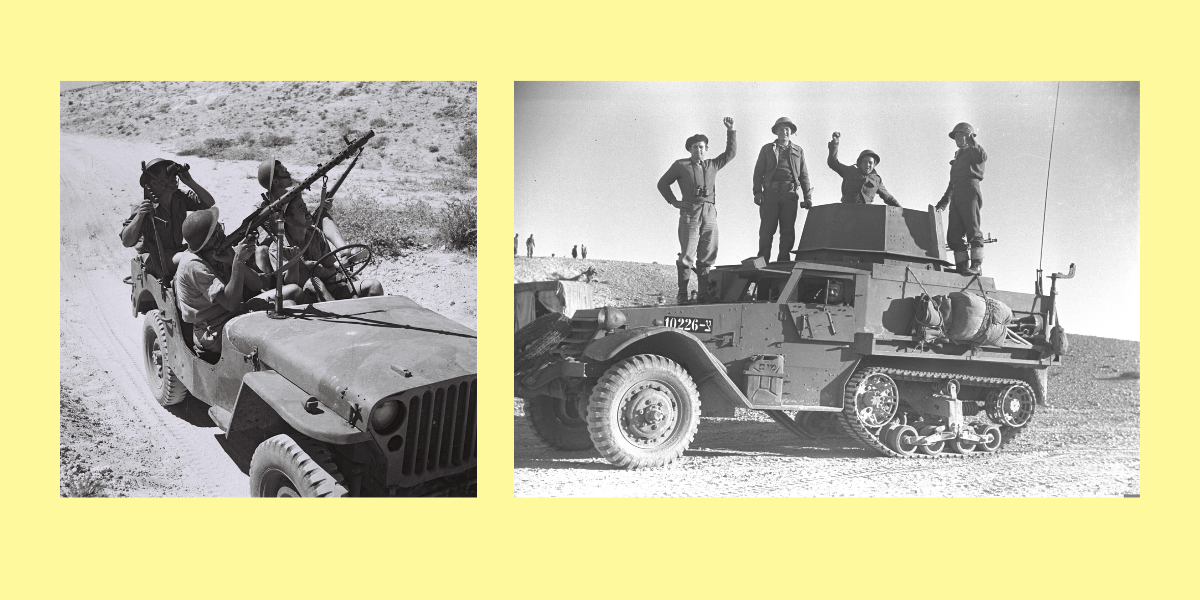

After the United Nations voted to partition Palestine into two states on November 29, 1947, a war with the Arabs seemed inevitable. Ben-Gurion, the head of the Jewish Agency and the de facto leader of the pre-state Jewish settlement known as the Yishuv, was painfully aware that the nascent state was in immediate need of a massive array of weapons to fight a real war. So he dispatched Eliezer Kaplan, the treasurer of the Jewish Agency, to America to raise funds. The goal was $7 million. He was unable to raise even a portion of that. In the wake of Kaplan’s failure, Ben-Gurion proposed going to the United States himself to raise the funds. Golda, then the head of the Jewish Agency’s political department, insisting that his place was in the Yishuv, offered to go in his stead.

She departed in January 1948 with a shopping list that included jeeps, rockets, speed boats, small warships, medical equipment, tents, blankets—just about everything else a newly formed army would need. While her colleagues hoped she would fulfill Kaplan’s goal of $7 million, she had higher aspirations: $25 million.

Prior to embarking on her fundraising efforts, she joined the Jewish Agency’s mission to the United Nations and attended Security Council meetings as an observer. At a press conference she gave at the United Nations’ temporary home at Lake Success on New York’s Long Island, she rather undiplomatically attacked the British for the deliberate chaos and bloodshed they were leaving behind as the British Mandate in Palestine was coming to an end after 30 years. Not only were they failing to protect the Jewish community, but they were also arming the Arabs and doing everything possible to place obstacles in the path toward a Jewish state.

While her appearance at Lake Success was important, it was the fundraising she did that made this trip memorable. When she had previously come to raise funds, her audiences had generally been committed Zionists who were, like her, immigrants or children of immigrants from Eastern Europe. Their mameloshn was Yiddish. They had hosted her in their homes, forced her to sit up late into the night describing the Yishuv’s wonders and proudly contributed the few dollars they had saved.

She had met some wealthy businesspeople before, but now she was going to meet a far broader, more powerful and wealthier swath of the American Jewish community. The General Assembly meeting of the Council of Jewish Federations was being held in Chicago. The participants represented the leadership, lay and professional, of virtually every Jewish community in the country. These were certainly not people who ever contemplated, even for a nanosecond, that Palestine was a place for them. In fact, some among them had opposed the Zionist enterprise. In the wake of the Holocaust, their opposition had waned, replaced by a grudging neutrality.

Now these Jewish leaders were caught between two fears: that a Jewish state might make them less secure in America and that there might be a repetition of the Holocaust tragedy, with Jews again finding no refuge. The right message could push them to support building the Jewish state. The wrong one would confirm their fears and hesitations about such a state and its impact on them as American citizens.

The federations’ ambivalence about the Zionist enterprise was evident in the fact that in the five months since the British announcement of their departure from Palestine and two months since the United Nations vote in favor of partitioning it into a Jewish and Arab state, they had not seen fit to include the topic of Palestine on their agenda. Admittedly, their main focus was on domestic matters. Yet one would have imagined they would have addressed, in some context, the welfare of close to 700,000 Jews in potential danger in the Yishuv.

Few of them had interacted with Golda previously. Those who had considered her a rather annoying Zionist apparatchik. Henry Montor, the professional leader of United Jewish Appeal, the organization that handled American Jewish overseas philanthropies, called her an “impecunious, unimportant representative, a ‘schnorrer.’ ” But he believed in the cause and knew there was a desperate need to find homes for Displaced Persons in the aftermath of the Holocaust. Setting aside his reservations, he pressured the Council of Jewish Federations to make room for her on the agenda. They allotted her 30 minutes.

Into that Chicago hotel ballroom on a very snowy Sunday, she brought the skills of persuasion that she had been honing since her days as a young girl in Milwaukee. There is a Jewish aphorism: “Words that come from the heart, enter the heart.” And so it was that day. Speaking without notes, she melded the Zionist message of Jewish strength with a very American “can-do” spirit.

“The Jewish community in Palestine is going to fight to the very end. If we have arms to fight with, we will fight with them. If not, we will fight with stones in our hands…. If these 700,000 Jews in Palestine can remain alive, then the Jewish people as such is alive and Jewish independence assured…. My friends, we are at war…. Our problem is time…. The question is: What can we get immediately?… I do not mean next month. I do not mean two months from now. I mean now….”

Then, breaking with the predilection of some Zionist emissaries to paint Jews in Palestine as better, stronger and more resilient than their counterparts outside the Yishuv (even though she probably believed they were), she told them: “We are not the best Jews of the Jewish people. It so happened that we are there, and you are here. I am certain that if you were in Palestine and we were in the United States, you would be doing what we are doing there.”

While the Yishuv desperately needed American Jewry’s financial support, she did not hesitate to insist that this time, contrary to the norm, the ones who paid the bills would not determine the tune. The Yishuv would make its own decisions, she insisted in her speech. “You cannot decide whether we should fight or not. We will. The Jewish community in Palestine will raise no white flag for the Mufti. That decision is taken.”

But then, making her audience almost full partners in the enterprise, she returned to the choice they could make. “You can only decide one thing: whether we shall be victorious in this fight or whether the Mufti will be victorious. That decision American Jews can make. It has to be quickly, within hours, within days.”

A clearly besotted audience member reported to those who had been unable to attend: “For 35 minutes she spoke…. Without emotion, never raising her voice, she told calmly the story of the defense of Jews in Palestine, of their homes and families…. Few personalities have ever received the ovation that greeted this woman of valor.” Montor, who had so personally disparaged her, recalled the “electric atmosphere” that prevailed in the ballroom and quickly began to arrange meetings for her in every city where there was a major Jewish community. He traveled with her from place to place, remaining awestruck by her abilities. “She had swept the whole community,” he once said.

By the end of that trip, she raised $50 million. Her success prompted Ben-Gurion to observe that one day it would be said of Golda: “There was a Jewish woman who got the money to make the state possible.”

Her visit marked a number of beginnings. Listening to her speak, American Jews’ internalized fear of a repetition of the Holocaust was replaced by—or at least conjoined with—a vision of a new future. She brought a message of hope, something that had been rare for Jews for the preceding decade. Her visit was also the beginning of a relationship Golda would have with the broadest manifestation of American Jewry. They would follow her loyally throughout her career, do what she asked of them and embrace her in a way that many of her fellow Israelis would not. For this generation of American Jews, she came to epitomize the long-suffering but absolutely resolute mother who would do anything for her people—even at the expense of her own well-being.

But she meant more than that. She also spoke of the new breed of Jew, the children at home, the ones who were ready to fight for their people’s survival and not depend on others to do so in their stead. She did not look like the young, tanned, open-collared, swaggering sabras who farmed and fought. But she spoke in their name and demanded of American Jewry that they not abandon them. From that visit on, she occupied a special place in the hearts of American Jews. Nothing would wrest her from it.

But this visit marked yet one more beginning, the beginning of the end of the American Zionist movement. The movement would, of course, grow exponentially during the 1950s and 1960s in the wake of the creation of the new Jewish state, when it would experience some of its strongest years.

But Golda, in reaching out to the “whole” community, was telegraphing a new, more all-encompassing message. Jews who make their home in America did not have to be committed Zionists or make aliyah to be part of this partnership.

Their fellow Jews who were building the Jewish state needed help, and they could offer it. And she repeatedly laid out the terms of the partnership. It had its responsibilities. But, she reminded them, it also had its benefits and rewards: “We certainly cannot go on from here without your help…. Believe me, my friends, that’s all we ask of you—to share in this responsibility with everything that it implies—difficulties, problems, hardships, but also joy,” she wrote in her 1975 autobiography, My Life.

Just three years after learning of the devastating reality of the Shoah, Jews were being asked to do something for other Jews—and to do it with joy. They were being asked to donate not until it hurt but until it felt good, joyously good. This was Golda’s genius.

Deborah E. Lipstadt, a longtime professor at Emory University and author of several books, currently serves

in the Biden administration as the special envoy to monitor and combat antisemitism.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply