Books

‘Once We Were Home:’ Stolen Children of the Holocaust

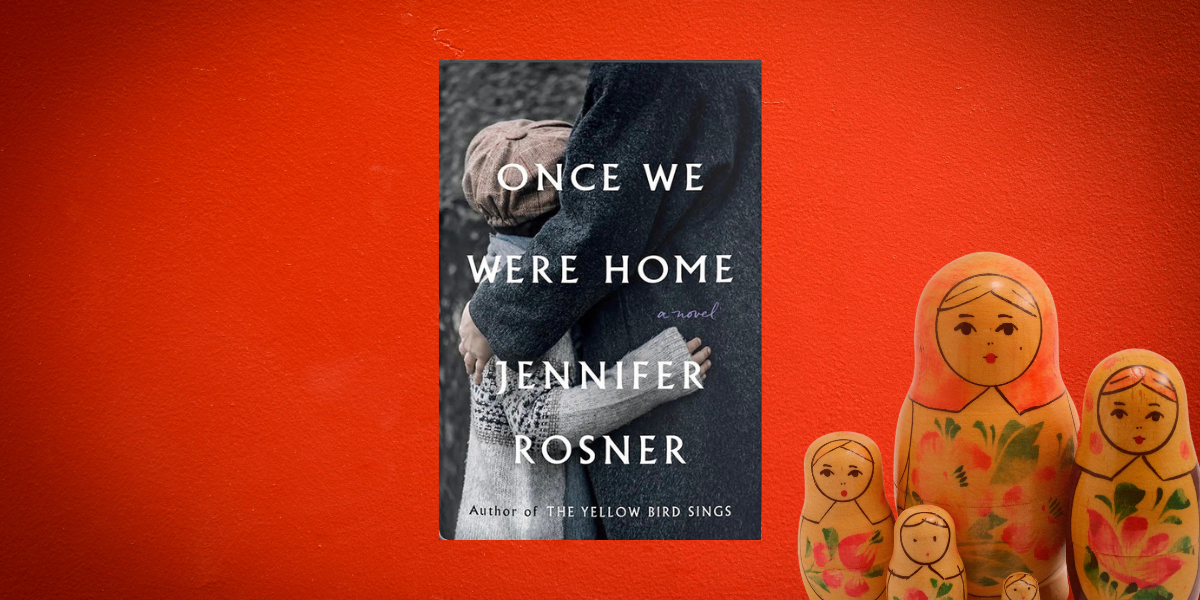

Once We Were Home

By Jennifer Rosner (Flatiron Books)

Jennifer Rosner begins her new novel from an unusual perspective: “My family’s song sets the rhythm of my heart as I nest inside my mother, inside her mother, inside her mother,” she writes, expressing the thoughts of the innermost doll in a set of nesting dolls. That metaphor instantly sets the theme of the intertwined stories that follow.

Rosner, whose previous novel, The Yellow Bird Sings, was a finalist for two National Jewish Book Awards as well as a One Book, One Hadassah book club selection, hauntingly evokes in her new work the inner and outer lives of those who, as children, were displaced, stolen and hidden during World War II. Some were placed in convents and monasteries; some were taken in by non-Jewish families. Those who looked Aryan were sometimes kidnapped and raised by Germans as their own children. After the war, many were reclaimed, sometimes forcibly, and transported to British Mandate Palestine.

The voices of the four main characters—Roger, Renata, Ana and Oskar—alternate by chapter, moving forward in time from war-torn Europe in 1942 to Israel in 1968. The characters’ stories converge unexpectedly as they attempt to move on from the trauma and loss they experienced as children during the Holocaust and build new lives.

Roger, placed in a convent in Marseilles during the war, has been asking questions since a young age: “Why, if God is good, did he create mosquitos that sting and bite us?” “Are there really roads to good and evil?” When relatives come to reclaim him, the Church whisks him away to a monastery in Spain until required by a court ruling to turn him over to his aunt. Despite being embraced by a loving family in Israel, he feels as if he’s “still afloat between two worlds, watching.”

Renata, a British student from Oxford, is on an archaeological dig in Jerusalem in 1968 when readers first meet her. Her chosen area of study reflects her fascination with excavating the past. She does not know that her German mother and father are not her biological parents. After the death of her mother, Renata is grief-stricken and tries to contend with unanswered questions about her life, including why her parents fled Germany when she was a child.

Ana and Oskar, born Mira and Daniel Kowalski, spend the war years hidden by Agata and Jozef Dabrowski, a Polish farming couple. Ana is the older sibling. She is left with the couple at age 7, and initially she clings to a photo of her parents every night before falling asleep: “She wants to imagine all of them home, Mama and Aunt Frieda bustling in and out, tending soup pots of steaming kneidel. Jars of plum marmalade lining the kitchen counter; herbs tied fresh and drying off the beam above.”

Oskar wasn’t yet 2 when the Nazis forced Jews into ghettos in Poland. He has no memory of his parents and feels that he doesn’t need to remember them, preferring to focus on “the fields and forests, and birds who trill and chirp and thwack and whistle.”

The Dabrowskis don’t want to give the children up after the war, but Ana and Oskar are taken from the couple by a Jewish woman from a reclamation organization and resettled in Israel on a kibbutz. Ana embraces kibbutz life, but Oskar is heartbroken and angry. Attempting to find his place in the kibbutz carpentry shop, he learns to craft magnificent nesting boxes. Remember those nesting dolls mentioned in the opening?

Rosner’s tender prose unearths the depth and complexity of family, love, religion, identity, memory and home. Lying deep within each character’s tangled feelings is the pivotal place of the mother. As a friend astutely comments on Oskar’s work, “What is a mother if not a nesting box?”

Rahel Musleah, a frequent contributor to Hadassah Magazine, runs Jewish tours to India and speaks about its communities.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply