Books

Fiction

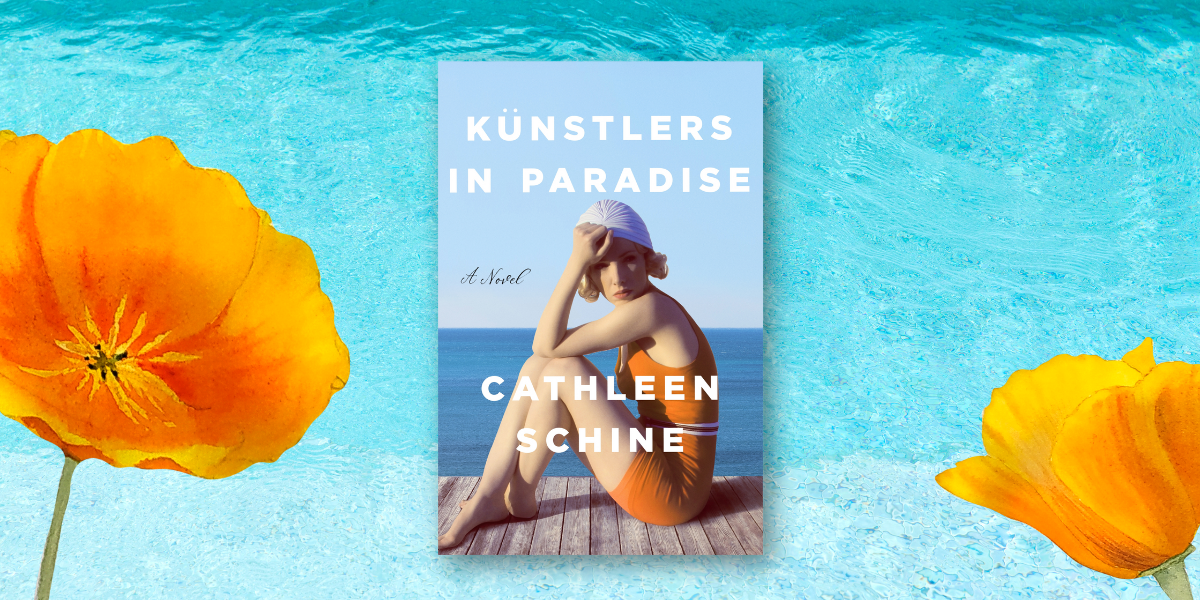

‘Künstlers in Paradise’

Künstlers in Paradise

By Cathleen Schine (Henry Holt and Co.)

The sun doesn’t have a fragrance, but in Cathleen Schine’s latest novel, readers can practically inhale the power of Southern California’s rays, just as they can almost catch a whiff of the bougainvillea, honeysuckle, jasmine and oranges blossoms blooming there year-round.

That’s one of the many magical infusions in Schine’s vivid and deeply felt work. It focuses on the 10,000-strong colony of German-speaking Jewish refugees—artists, writers, musicians and scholars—who were assembled as a brain trust of sorts in Los Angeles after the rise of Nazism in their native cities of Berlin, Munich and Vienna. They included Lion Feuchtwanger, Arnold Schoenberg, Vicki Baum, Berthold and Salka Viertel and many others who worked for the Hollywood studios, taught at UCLA and contributed vastly to Southern California’s cultural and intellectual scene.

Some of these dramatis personae have secondary and tertiary roles in the book, but the star of the novel—and she burns brightly—is Viennese-born Salomea Künstler, better known as Mamie, a feisty, sharp-tongued nonagenarian who is sharing the story of her life, and the Hollywood artist colony, with her somewhat aimless 20-something grandson, Julian. It is 2020 and the two are holed up in Mamie’s comfortable but slightly disheveled digs in Venice, Calif., waiting out the Covid-19 storm.

ONE BOOK, ONE HADASSAH EVENT

Join us on Thursday, August 17 at 7PM ET as Hadassah Magazine Executive Editor Lisa Hostein interviews best-selling author Cathleen Schine about her latest book, Künstlers in Paradise. This event is free and open to all.

All of Mamie’s stories are engaging to Julian (and to this reader), but the most affecting ones focus on the sense of physical and psychological displacement of Mamie’s elders. The move from Vienna—where the Künstlers had made names for themselves over multiple generations in music, medicine and commerce—to Los Angeles had clearly taken its toll. Language, age and middling talent served as formidable barriers to the reinvention of the self.

After all, Schine gently suggests, not everyone can be a Schoenberg, the father of atonal music. In Vienna, Mamie’s own father, Otto, had been a respected composer; in Santa Monica, he was relegated to teaching piano scales to children with no aptitude for music.

“Loss, which Otto had so heroically faced at first, had soured to a sense of abandonment,” Schine writes. “Both his old country and his new country had abandoned him. The new country is bright, but my future is dark: that’s what he began to say.”

One of Schine’s greatest gifts as a novelist is her capacity to capture the light and the dark in the flash of a moment, leaving the reader with a sense of life’s preciousness and precariousness—a hint of orange blossoms wafting in the air, along with the heartache of love lost and things past.

Robert Nagler Miller frequently writes about the arts, literature and Jewish themes from his home near New York City.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply