Arts

Feature

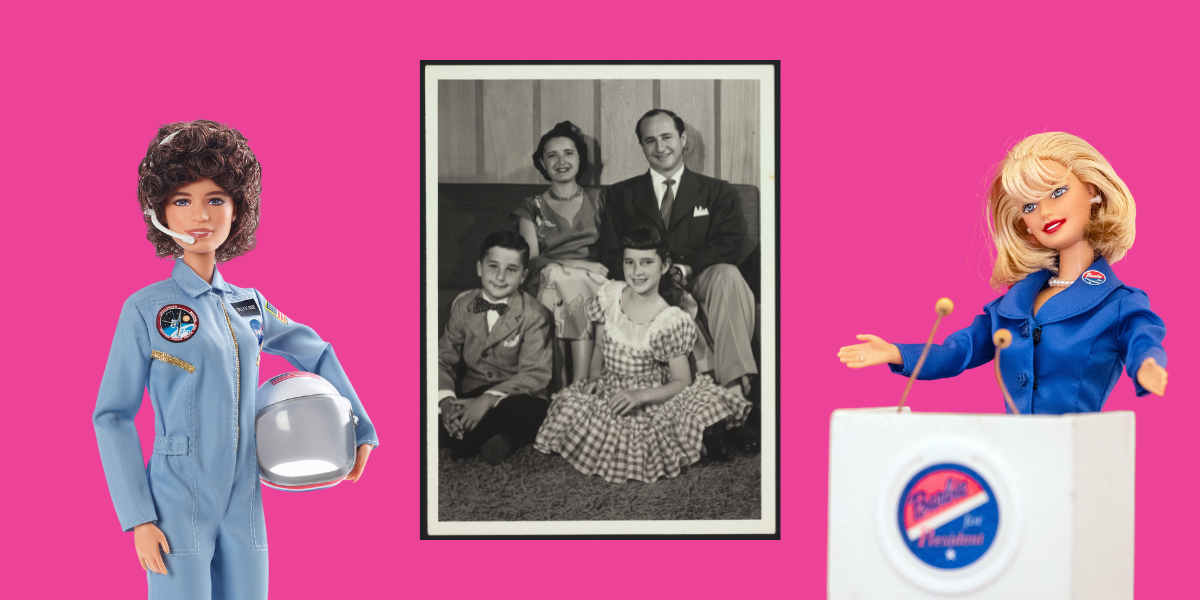

Barbie’s Jewish Mother

Leave it to a Jewish mother to create the world’s most iconic doll. Barbie isn’t affiliated with a specific religion, but her roots trace back to Ruth Handler, the daughter of Polish Jewish immigrants.

After arriving at Ellis Island, her father, Jacob Mosko, moved to Denver to work on the railroad before starting his own trucking company.

From a young age, Handler, the youngest of 10 children, heard her Yiddish-speaking parents’ stories of Poland and how antisemitism impacted the family financially. To make ends meet, everyone worked, including the women.

Handler inherited her father’s entrepreneurial spirit and his gambling gene, although she preferred to roll the dice in business rather than at the craps table. When it came to creating a doll that would appeal to young girls, she was willing to risk it all, potentially jeopardizing the future of Mattel, the toy company she helped create with her husband, Elliot.

Handler met Elliot at a B’nai B’rith dance in 1932 when they were in high school, and the couple married in 1938. Though his grandfather was a rabbi, the yeshiva was not for him.

Elliot was an artist and an inventor. When he and his friend Harold “Matt” Matson started making Lucite picture frames in their garage, Ruth began selling them. By 1945, the three had formed Mattel, combining both men’s names, despite Ruth being the driving force behind selling their products.

Matson exited the company in 1946, leaving the Handlers at the helm. When you mixed Elliot’s talent with Ruth’s moxie, they made an unbeatable team.

Thanks in part to the Barbie movie set to open nationwide on July 21, starring Margot Robbie and Ryan Gosling, the doll is at the height of her popularity. But that wasn’t always the case. Early on, Handler faced an up-hill battle trying to convince Mattel’s all-male board of directors, including her husband, that a doll with breasts was suitable for little girls.

Handler got the idea for a grown-up doll in the early 1950s, after watching her children at play: Kenneth had toy guns, trucks and soldiers whereas Barbara had baby dolls, reinforcing the narrow notion that little girls should grow up to be housewives and mothers. The only fashion dolls at the time were paper dolls, which looked like adult women, but the clothes were flimsy and held in place by even flimsier tabs, resulting in more frustration than fun for Handler’s daughter and her peers. She wanted to create a doll that would empower girls to believe they could do and be anything.

That idea wouldn’t take shape until several years later. In 1956, while vacationing in Europe, Handler passed by a cigar shop and spotted a novelty gag doll in the window. Her name was Bild Lilli, and she was a prostitute, based on a character in a German comic strip for adults. Despite her occupation, Bild Lilli was exactly the type of doll Handler had been envisioning. She bought two: one for her daughter and one for the men at Mattel, who thought the doll was inappropriate, insisting that mothers would never go for it.

It was a three-year slog to produce Barbie. After finally getting Mattel on board, Handler had to find a cost-effective way to manufacture the doll. Creating a figure with rooted hair, detailed makeup and soft plastic took a feat of engineering. Then came the wardrobe and the challenges of designing high fashion at one-sixth the scale of a real woman. Through fits and starts, Barbie was perfected.

But, when Mattel launched her at the 1959 American Toy Fair in New York City, the doll was a flop. Handler, however, refused to admit defeat. That June, when school let out for the summer, Handler began airing a Barbie commercial during The Mickey Mouse Club, a children’s television show. With an infectious jingle, the commercial showcased the “Teenage Fashion Model” (Barbie’s first career) wearing her signature zebra-striped swimsuit and an array of party dresses. Soon, little girls everywhere began clamoring for Barbie. The rest, as they say, is history.

By the early 1960s, Mattel was flooded with fan mail from girls asking for Barbie to marry her perpetual boyfriend, Ken, and have a baby. Handler refused, not wanting to reinforce the idea that young girls should aspire only to marriage and motherhood. Despite donning numerous wedding gowns, Barbie has never walked down the aisle. Instead of a baby, in 1964, Handler gave Barbie a kid sister, Skipper.

The ever-independent Barbie has pursued more than 200 careers. She’s been everything from a fashion designer, nurse and astronaut (back in the 1960s) to a surgeon and Olympic skier (1970s) to a presidential candidate (early 2000s). More recently, she embarked on a career in STEM—a far cry from 1992’s “Teen Talk” Barbie who, with a pull of a string, uttered those damning words: “Math class is tough.”

That wouldn’t be the first or last time that Barbie met with disapproval from feminists. In 1976, Mattel released “Growing Up Skipper,” a doll that went from flat-chested pubescence to breast-sprouting womanhood with the crank of her arm. The outrage was swift and added to the criticism of Barbie, who’d already been blamed for causing body dysmorphia, eating disorders and low self-esteem among girls.

Yet for every Barbie hater, there have always been twice as many who embraced her. Today, the doll is available in nearly two dozen skin tones as well as multiple hair and eye colors and body shapes. And earlier this year, Mattel released a Barbie with Down syndrome.

As a historical novelist, I was immediately drawn to Ruth Handler’s story in much the same way I’d been drawn to write about another Jewish trailblazer, Estée Lauder, in Fifth Avenue Glamour Girl. Both Lauder and Handler, who died in 2002 at 85, were tough, hardworking women who had a lot of chutzpah.

As I close in on the first draft of my Ruth Handler novel, my promise to readers is this: Whether you loved playing with Barbie or shaved off all her hair in a fit of protest, my novel, The Doll Makers, will speak to the feminists in all of us.

Renée Rosen is a USA Today best-selling author of historical fiction, including Fifth Avenue Glamour Girl.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Jeri Collins says

Great article! Can’t wait to read the book. Such a fan of your work.

AMY MILLER COHEN says

One typo in the article; at the end of the article it directs the reader to page 48 for the book review by Renee Rosen; the correct page is page 47

One addition: Tiffany Shlain made a wonderful, short documentary now on YouTube r titled THE TRIBE. IT IS THE HISTORY OF THE JEWS AND THE HISTORY OF THE BARBIE DOLL. I WAS SURPRISED IT WASN’T MENTIONED IN THE ARTICLE.

Ann Weinblad says

I loved the article. I wanted to call up my daughter and tell her to read it. My gierls all had Barbies and my mother made many clothes for the dolls.

Sharon Schneider says

Enjoyed reading this. My mother-in-law Was friends with Ruth Handler. I want to have a group zoom with my group about this.

Thank you

Sharon Schneider

Phyllis Silverberg says

What a fascinating article! Of course I had Barbie and Ken dolls in the early 60s! I’m so impressed that they made one with Downs Syndrome!

Nadine King PhD, RDN says

I do believe that Mollie and Joe Greenberg at Premier Doll Clothes constructed the Barbie clothes. They lived in Brooklyn. After a toy show in Manhattan, they gave me the Barbie and clothes that were displayed.