Arts

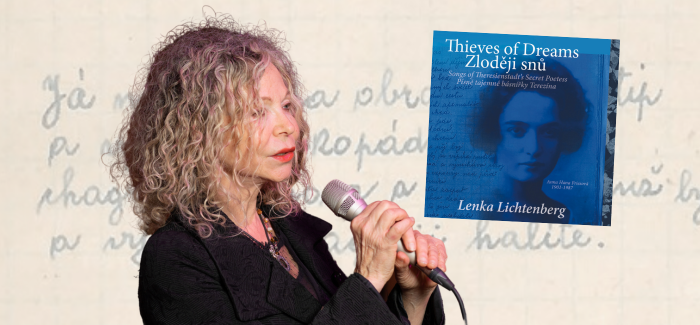

Lenka Lichtenberg Sets Holocaust Poetry to Music

The poem, entitled What Is This Place?, reaches in opposite directions: “We’re eternally lost/ and eternally redeemed/ In the darkest of nights/ remember the sun!” The dichotomy in the phrases gains added poignancy once you learn that it was written in a concentration camp.

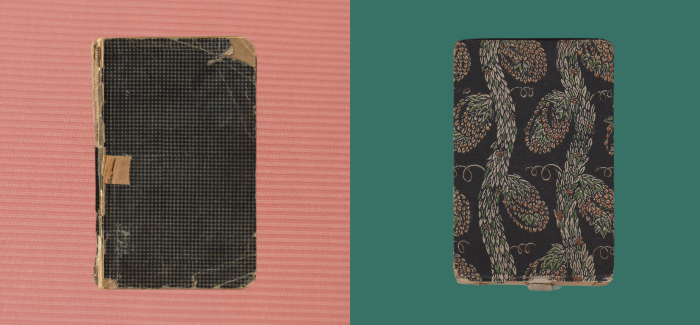

The poet, Anna Hana Friesova, was imprisoned in Terezin, north of Prague, with her husband—who was ultimately murdered in Auschwitz—and her daughter, Jana Renee. Mother and daughter walked out of Terezin when it was liberated by the Red Army in May 1945. And 65 of Friesova’s poems, filling two notebooks, never saw the light of day.

Fast forward to 2016. Lenka Lichtenberg, Friesova’s granddaughter and an award-winning singer-composer and cantorial soloist living in Canada, had returned to her native Prague in order to go through the belongings of her mother, who had recently passed away. As she opened a desk drawer safeguarding the notebooks, Lichtenberg simultaneously opened a door to the past.

It took Lichtenberg almost two years to decide what to do with the poems, which are filled with nightmares and dreams, grief and miracles. While she had many memories of her maternal grandmother, Lichtenberg hadn’t known that she—gone 30 years at that point—was a poet. No one did. A friend suggested she give the tattered pages to Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, but she decided otherwise.

“I felt some ownership,” Lichtenberg said in a recent interview. “It’s my grandmother. I think I can do something more meaningful. If I set them to music, I can make my grandmother and her life as a poet live.”

The decision led to the creation of Thieves of Dreams, the artist’s 13th album, performed in Czech and released in May 2022. She composed music for eight poems and enlisted a cadre of composers to create music for eight more.

On March 12, 2023, the collection won her the Juno Award—Canada’s highest music honor—for Global Music Album of the Year.

Making her grandmother’s poems sing is true to form for Lichtenberg. “Everything important in my life has happened thru music,” she said.

She began playing the piano at age 6 and by 9 she was a child star, singing in a popular musical theater act and on radio. But as she became known to much of the Czechoslovakian public, there was one key fact the young prodigy didn’t know about herself: Scarred by history, her mother never told her she was Jewish. (Lichtenberg’s father was not Jewish.)

That changed when an invitation came to sing at a holiday show when she was about 10 at the Prague Jewish Community Center. While traveling in a streetcar on the way to the performance, Lichtenberg vividly recalled her mother unveiling the secret with a pregnant, “By the way….”

She sang popular Czech songs at that first show before a Jewish audience, but when she was invited back, Lichtenberg worked with a cantor and learned some Hebrew and Yiddish songs phonetically. As she continued her music studies and eventually emigrated—first to Denmark, then to Canada—an inner conversation that began on that streetcar unfolded.

My mother saw being Jewish as a burden, a risk of becoming a victim,” recalled Lichtenberg. Even after the revelation, both her mother and grandmother rarely discussed their experiences at Terezin. “For me, embracing my heritage was first an act of defiance, then a way to love and honor my roots through learning, creating and sharing Yiddish and cantorial music.”

Lichtenberg’s raw talent is evident in videos of childhood performances, notably singing with famed Czech comedian Jiri Suchy, but there are many layers to her art.

She has an expansive musical worldview: In her albums, she sings in Czech, Yiddish, Hebrew, English, French and Russian. She began her adult career as a club and lounge singer and moved into rock, jazz and folk. It was on her first visit to Israel, in 1987, that she realized her true calling was Yiddish and Jewish music. As a newcomer to Yiddish—unspoken in her family for generations—her interest was less in prewar nostalgia and more in a contemporary world music sound.

Among her projects have been pairing Yiddish and Iraqi Jewish themes with Israeli violinist and oud player Yair Dalal in the Lullabies From Exile project; and a musical dialogue, called Bridges, with Palestinian Canadian artist Roula Said. Lichtenberg also appears on two tracks of the album Silent Tears: The Last Yiddish Tango, released in January 2023, which intertwines Warsaw’s prewar status as the European capital of tango with postwar Holocaust poems and testimonies.

She is currently planning a second edition of Thieves of Dreams, with songs performed in English.

Comfortable with where that long-ago streetcar took her, Lichtenberg assigns no blame for the delayed discovery of her Jewishness. Accepting the Juno Award at a ceremony in Edmonton, in Alberta, she thanked her husband, children, publicist and manager, adding, “Mainly I want to thank my mother and grandmother, who created this album for me….”

Though she sees her grandmother’s notebooks as a gift, seven years after their discovery, Lichtenberg still finds it hard to square the image of the woman she recalls from her childhood with the poet she found as an adult. “It’s hard to put the two sides together,” she observed. “It’s like two different people. Did she purposely turn off the person who lost so much—her husband, parents, family? Maybe it was her way of moving on. And she really did move on, beautifully…. In my memory she’s still the happy, fun-loving person I knew before. I feel so privileged I had the opportunity to discover her alter ego.”

And what about the next generation of the family? The music for “What Is This Place?”—lead track on Thieves of Dreams—was composed by Rachel Cohen, Lichtenberg’s daughter.

Alan M. Tigay is editor emeritus of Hadassah Magazine. He writes about music from around the globe at World Listening Post. For a full review of Thieves of Dreams, go to worldlisteningpost.com/2022/08/25/lenka-lichtenberg-thieves-of-dreams.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply