Being Jewish

Commentary

The Essence of Judaism? Disrupting It.

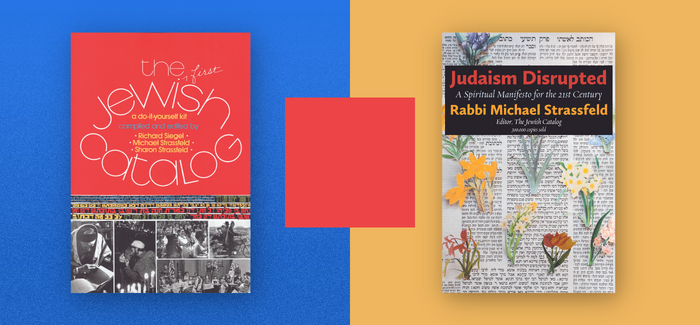

Fifty years ago, the first Jewish Catalog began a revolution in Jewish life. With this do-it-yourself kit, people for the first time could own their own Judaism and experience the richness and joy that I and the other editors of the Catalog believed would make a stronger Jewish community. The first Catalog, which we summarized as “a compendium of tools and resources for use in Jewish education and Jewish living,” taught hundreds of thousands of people how to make challah and even matzah, how to tie fringes on a tallit and how to build a sukkah.

The Catalog’s enormous success suggested we were right, and yet, a half-century later, I and others have new questions. We know “how” to do all these rituals—or we can Google whatever we need to know.

What we now need—I believe urgently—is “why.” Or more to the point, why bother at all?

What is the essence of Judaism and Torah? Many people would answer that it is observing the laws, customs and rituals of the Jewish tradition. In fact, Judaism is, at its heart, a revolutionary tradition that seeks to change rather than uphold or preserve the status quo.

Nowhere is this clearer than the holiday of Passover. The centrality of the Exodus in Judaism goes beyond the repeated notion that we must remember that we were slaves and therefore treat other people with compassion, especially those on the margins of society. As important as the commitment to social justice is, there is something even more important that we learn from this story.

Having left the bondage of Egypt, the people of Israel appear to be free, but they quickly discover the difficulties of living in freedom. During their 40-year journey to the Promised Land, the formerly enslaved people constantly express a yearning to return to Egypt, likely because with freedom comes responsibility and the need to make difficult choices.

In a radical text by the 19th century Hasidic master called by the name of his main work, Sefat Emet, the purpose of the revelation of the Torah is actually to help the people be free. In his commentary on the Torah portion Ki Teitze, he writes:

The purpose of all the commandments, both positive and negative, that were given to Israel is so that every person in Israel shall be free. That is why the liberation from Egypt comes first [before the giving of the commandments]. Torah then teaches the soul how to maintain its freedom by not becoming attached to material things. These are its 613 counsels. Every mitzvah/commandment in which the liberation from Egypt is mentioned tells us yet again that by the means of this mitzvah one may cling to freedom…. This is the purpose of the entire Torah.

This teaching suggests that we can be enslaved without ever being in bondage. Most people today are not physically enslaved and yet they are not really free. In the words of the 20th-century psychologist Erich Fromm, we often want to “escape from freedom” when we feel burdened by our fears and insecurities. We can live a life bounded by the limitations of our expectations, or a life circumscribed by the lack of faith in our abilities.

In the Sefat Emet’s understanding, Torah is first and foremost about freedom. The Torah is not about 613 commandments but rather 613 counsels that teach us how to obtain freedom. For example, he looks at the biblical practice of leaving the corners of the field untouched, which the text says is so that the poor can harvest them. For the Sefat Emet, we learn from this practice not to become too attached to material possessions. Our biggest challenge is to take the precious gift of life and do as much as we can with it.

The Torah understands the lure of Egypt and how easy it is to become enslaved, how past patterns can keep us chained to unwise or even harmful behavior. Passover reminds us that we were once enslaved and we became free. This is the real gift of the Exodus—the experience of freedom.

It is with the Sefat Emet text in mind that I began to write Judaism Disrupted. Too often, Judaism seems disconnected from the issues and challenges in our lives. The traditional liturgy and many of Judaism’s rituals leave us wondering what larger purpose they intend to convey. The challenge is to reimagine those practices as helpful aids to more purposeful lives.

It has become clear to me that we also need new practices that speak to the contemporary moment. In this reframing, each holiday enables us to concentrate on a key aspect of our lives. On Passover, we refrain from eating leavened bread, which is permitted every other week of the year. This allows us to focus our attention on food itself and the way it often weighs us down: Do we eat in healthy ways? Do we sometimes binge on snacks, hoping in vain that food will fill an emotional need? What if, during one meal each day of Passover, we slow down the pace of our eating to help us pay attention to an aspect of daily life that is often challenging?

A “Judaism disrupted” also envisions repurposing traditional practices so that we can cultivate inner qualities, such as gratitude, satisfaction and equanimity. For example, it is traditional to hang a mezuzah on the doorpost of our homes. The mezuzah contains a parchment with selections from the Torah and is intended to remind us to live a holy life. While many Jews have a mezuzah on the front door, it often becomes invisible. A new morning ritual would have us pause at the mezuzah as we leave home and acknowledge the blessing of a new day. Remember to take your keys, your cellphone and a moment of awareness as you exit. When you return home, take another moment to leave the distresses of the day outside and enter your home with a sense of peace.

With a mixture of reconstructed old practices and ones that are newly created, we can create a Judaism for the 21st century. In so doing, we can replace anger with open heartedness, yelling with listening, judgment with compassion. Freedom from the things that hold us back begins on the individual level but can spread outward into a world that desperately needs redemption.

How does freedom come about in Egypt? God asserts that redemption will come through God’s yad hazakah and zeroa netuyah—a strong hand and an outstretched arm. Usually, these words are understood as synonyms—metaphors for God’s power, which brings the plagues and eventually causes Pharaoh to let the Israelites go.

It is true that every struggle for freedom requires a steadfast commitment to the cause. Even nonviolent causes like the civil rights movement needed people who not only were willing to work for freedom but also were willing to be arrested and even risk their lives by protesting the injustice of segregation. Struggles for freedom require a yad hazakah—a willingness to stand up and protest and to keep standing up. They also require a zeroa netuyah—an outstretched arm.

An outstretched arm doesn’t have to be another metaphor for a hand of power. It can also be a hand extended to help someone to get up off the ground. It is a hand of welcome, of connection and support. Those hands are just as important as the hand of powerful resistance to injustice. Standing together while marching for freedom is how freedom comes about.

Operating both in the wider world and within ourselves, the most important hand to freedom is one’s own—passing over what is and touching what could be.

Rabbi Michael Strassfeld is an editor of the Jewish Catalog series, author of The Jewish Holidays and co-author with Rabbi Joy Levitt of A Night of Questions: A Passover Haggadah. He is rabbi emeritus of the Society for the Advancement of Judaism in Manhattan and writes a free weekly newsletter on the Torah portion (subscribe@michaelstrassfeld.com). This essay is adapted from his newly published book, Judaism Disrupted: A Spiritual Manifesto for Our Time (Ben Yehuda Press).

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply