Books

Feature

Essential Reads: Women of Color Navigating Jewish Identity

A prayer shawl of many colors enfolds today’s Jewish community, a population that, like America as a whole, is increasingly diverse. The Pew Research Center study “Jewish Americans in 2020” reported that 15 percent of those aged 18 to 29 also identified as Black, Hispanic, Asian, multiracial or other ethnicity. The study additionally found that among American Jews 30 and under, 29 percent are members of households that include one or more individuals who identify as Black, Hispanic, Asian, multiracial or other ethnicity.

Given these numbers, it is hardly surprising that Jewry’s multicultural mix has brought forth a plethora of books that describe that diversity. Recent offerings include memoirs such as Marra B. Gad’s The Color of Love and Nhi Aronheim’s Soles of a Survivor and histories like Once We Were Slaves by Reed College professor Laura Arnold Leibman. There are Speaking of Race, a how-to guide from journalist Celeste Headlee, and an essay collection titled The Racism of People Who Love You from Samira K. Mehta, a professor of women and gender studies as well as director of the Jewish Studies program at the University of Colorado Boulder. Taken together, these volumes provide a welcome entrée into engaging in tough conversations around the differences as well as the similarities among Jews today.

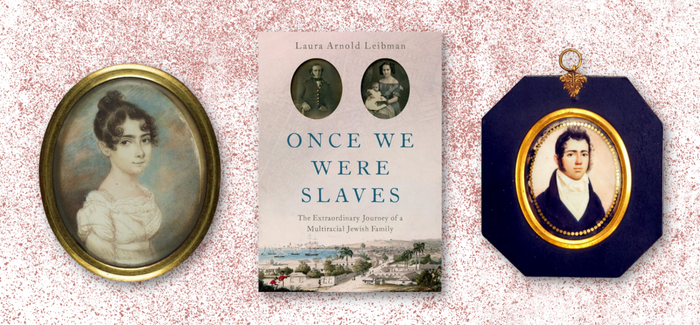

But is the composition of today’s American Jewish population that different from past generations? Far less than you might imagine, according to Leibman. In Once We Were Slaves: The Extraordinary Journey of a Multiracial Jewish Family (Oxford University Press), she traces the roots of wealthy New Yorker Blanche Moses, a descendant of one of the oldest and most prominent Jewish families in the United States, to the 18th century Black and Jewish communities on the Caribbean islands of Barbados and Suriname.

Starting with objects passed down through the generations—two painted ivory miniatures of Moses’s ancestors, Sarah Brandon Moses (1798-1829) and her brother Isaac Lopez Brandon (1793-1855)—Leibman unravels the family’s stories. Both Sarah and Isaac were born “poor, Christian and enslaved,” Leibman writes. Although their father, Abraham Rodrigues Brandon, was one of the wealthiest and most influential Jews in the Sephardi community in Barbados, their mother—Abraham’s common-law wife, Sarah Esther Lopez-Gill—was of both white and African ancestry and was born enslaved to a Christian household.

Moreover, Leibman notes in the book, “Sarah and Isaac were not the only people in this era who had both African and Jewish ancestry. The siblings’ story reveals the little-known history of other early multiracial Jews, which in some of the places the Brandons lived [in the Caribbean] may have been as much as 50 percent of early Jewish communities.”

What distinguishes the story of Sarah and Isaac, Leibman writes, is their father’s wealth and ambitions for his offspring that offset many of the challenges they faced because of their mixed heritage. His influence in the Caribbean Jewish community smoothed the children’s conversion to Judaism and their eventual acceptance in the local congregation, which he headed. He helped pay for their freedom and, just as important, brought them to England and guided their entrance as white Jews into the Jewish communities of Britain and the United States.

VIRTUAL PANEL: Join us on Thursday, March 16 at 7 PM ET as Hadassah Magazine Executive Editor Lisa Hostein moderates a discussion that will explore issues of identity and belonging that have motivated a growing number of Jewish women of color to write about their experiences. Panelists include Celeste Headlee, author of Speaking of Race: Why Everybody Needs to Talk About Racism—and How to Do It; Samira K. Mehta, author of The Racism of People Who Love You; and Emily Bowen Cohen, whose graphic novel for children, Two Tribes, will be published this fall. Register here.

Sarah eventually met and married Joshua Moses and moved to New York City. When her brother applied for American citizenship, he similarly had no difficulty meeting the requirement that he be a free white man. Over the decades that followed, their origin story gradually faded into obscurity.

Alas, so did the stories of other Jews of mixed race ethnicity, resulting in the history of the Black Jewish experience becoming mostly invisible, writes Leibman. This absence feeds the mistaken assumption that a person whose skin color is not white is also not Jewish.

Leibman cites instances throughout the 19th century and later when Jews of color were confronted in American synagogues about who they were and why they were there.

“Prejudice is also part of the story of American Judaism,” Leibman writes in the prologue to Once We Were Slaves. “I hope by recognizing that past we will continue to move forward toward a more equitable and inclusive future.”

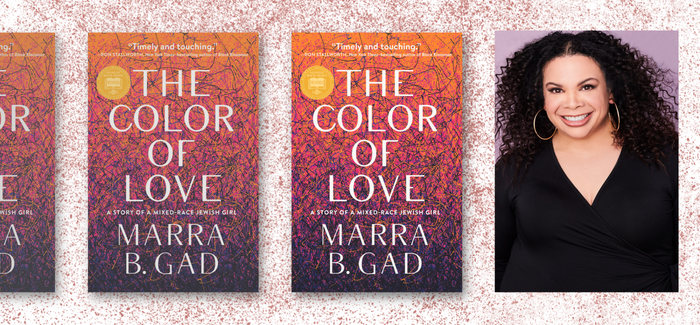

Bias in the Jewish community is brought to the fore in Marra B. Gad’s powerful memoir, The Color of Love: A Story of a Mixed-Race Jewish Girl (Agate Bolden). Born to an unwed white Jewish mother and an unnamed Black father, Gad, an independent film and television producer in Los Angeles, was adopted by a Jewish family in Chicago as an infant.

“In the Jewish community, there has always been some level of confusion around the nature of my brown existence—especially around the notion that I was born a Jew and that I did not convert to become one,” she relates in her book. “To this day, I am routinely asked when I go to synagogue if I am ‘in the right place.’ I am assumed to be ‘the help’—the kitchen help, someone’s nanny. Rarely am I simply welcomed with a smile like my Eastern European-looking family members.”

Enveloped by a loving and supportive family growing up, Gad writes about feeling nurtured by her family but confused when subjected to the racism of others because she is biracial. In The Color of Love, she recounts stories about Jews who couldn’t believe she was really Jewish and about members of the Black community who regarded her as not Black enough.

There were neighbors and strangers alike who puzzled over why she did not have the same skin color as her parents and “nice Jewish boys” who wouldn’t date her because, they told her, they wouldn’t know how to explain her to their parents.

The cumulative impact of this constant scrutiny of her appearance and the questioning of her belonging “warped the lens with which I viewed myself,” she writes.

What helped sustain her, however, was her belief “that we are all born as loving beings” and the determination that she could not respond to other people’s hatred with more hatred. “I stand with two feet solidly planted in love,” she writes. “Because I know what it is to be deemed unworthy and hated because of my skin color and because of my religion. And because I will not be an instrument that puts more hate into the world.”

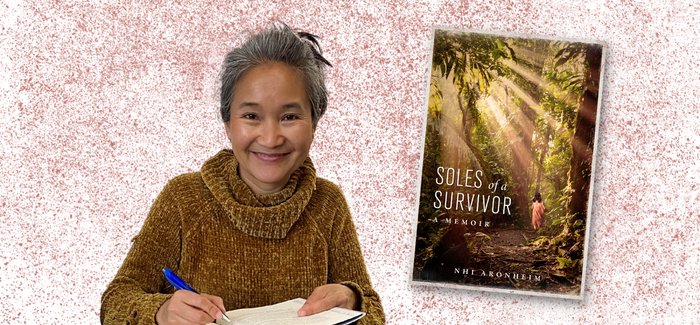

There are many multicultural paths to Judaism. Nhi Aronheim’s is, perhaps, among the most distinct. Today she lives in Denver, where she is a longtime member of Hadassah and where she and her family are part of a Conservative Jewish community. She was born in the 1970s, however, in a very different world, in what was then South Vietnam, and grew up in poverty in the slums of Ho Chi Minh City, as she relates in her memoir Soles of a Survivor (Skyhorse Publishing).

The book describes how, at the age of 12, without her family, she made a perilous escape that took her through the jungles of Cambodia to a refugee camp in Thailand. She lived there for two years until she qualified for refugee status and came to the United States, where she was adopted as a teenager by a Christian family in Louisville, Ky., and began to assimilate into mainstream American culture.

She faced another kind of acculturation when, after she finished college and began a successful career in telecommunications, she met her husband-to-be, Jeff, who is Jewish. When he asked her to consider converting, together they visited a variety of synagogues and chose one where, even though she was the only Asian face in the sanctuary, she felt welcomed and accepted by the other members. The rabbi, however, treated her wish to convert with skepticism and encouraged the couple not to join.

After they were married, Aronheim and her husband returned for a second interview with the rabbi after which he agreed, still somewhat grudgingly, to oversee her conversion and affirm their synagogue membership. “The process of conversion was challenging,” she writes. “It’s difficult for most people, but it was particularly difficult for me, an Asian woman adopted into a Christian household.”

Despite those difficulties, like Gad, Aronheim chooses to focus on love.

“Now I relish being a Vietnamese Jew,” she writes, noting the importance of radiating “goodness to those we meet” regardless of their religion and background.

Two important new essay collections answer questions around how to navigate and talk about prejudice, both in the Jewish community as well as the larger society.

Award-winning journalist Celeste Headlee frequently addresses the topic both in her writing and as president and CEO of Headway DEI, a nonprofit that consults on diversity issues for journalists and the media.

Her background, she notes in her most recent book, Speaking of Race: Why Everybody Needs to Talk About Racism—and How to Do It (Harper Wave) gives her a unique perspective.

“Because I am a light-skinned Black Jew, sometimes called ‘racially ambiguous,’ I’ve been talking about race for as long as I can remember,” she writes. In thoughtful, careful detail, interspersed with anecdotes from her own life and the people she has met, she breaks down fraught racial issues. Emphasizing the importance of having conversations, “lots of short, low-stakes conversations,” she gives examples of strategies and techniques that will help foster calm, productive dialogue.

“The truth is that everyone is biased. Everyone. We all make assumptions about people based on superficial observations,” she writes in the forward. Her book is intended to help readers “recognize that you can disagree with someone strongly and yet have the conversation anyway. Debates have changed very few minds, but conversations have the power to change hearts.”

In an email interview, Headlee talked about some of the biases in the Jewish community and the importance of being more sensitive and welcoming to Jews of color. She counseled synagogue members to embrace Jews of color wholeheartedly. “Show them that you are happy to see them,” she said.

“That’s how you include that person in your service. Don’t instruct them or teach them how the service is going to go—which is really common—because it’s possible they’ve been going to synagogue their whole lives. It’s possible they had a bar mitzvah,” she said. “They may be as schooled in Judaism as anyone else there, so telling them how things go can be extremely condescending.”

READ MORE: How to Make Jews of Color Feel Comfortable in Jewish Spaces

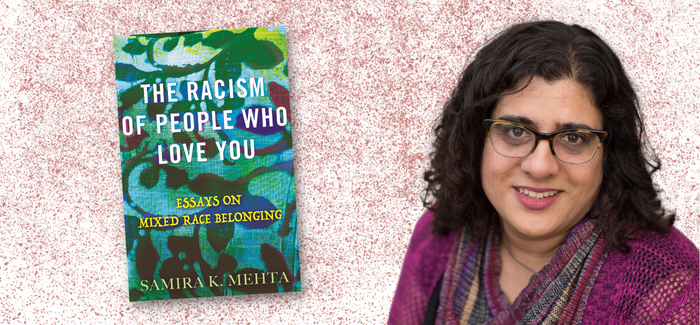

Samira K. Mehta’s The Racism of People Who Love You: Essays on Mixed Race Belonging (Beacon Press) touches on similar issues. However, Mehta’s book is less of a how-to than a collection of meditative essays that range from the personal to the political. By book’s end, we have gotten to know her—and trust her insights. The author of a previous book, Beyond Chrismukkah: The Christian-Jewish Interfaith Family in the United States, Mehta also heads the “Jews of Color: Histories and Futures” project, an initiative that studies the experiences of Jews of color in the United States, at the University of Colorado Boulder, where she teaches.

In one of the book’s most engaging essays, “Where Are You Really From?: A Triptych,” she helps readers understand her frustration when people she has newly met ask her, a bit too insistently, just that question. The reason, she explains in the book, is because even after she answers, truthfully, that she was raised outside of New Haven, Conn., too often the follow-up question is, “But where are you really from?”

To Mehta, a Jew by choice who is the daughter of a white Protestant mother from the Midwest and an immigrant father from India, the query can sound nosy or, worse, insulting. Is the person she has just met insinuating that she does not really belong—that she is not really Jewish, or really white or really South Asian?

In a Zoom interview, Mehta added that slights like these may be thoughtlessly unintentional, but they sting nonetheless for their suggestion that she is an outsider. But you can—and should—try to mend the hurt by talking about it, she said.

“If your intent was not to make me feel bad, but just curiosity, then you must actively listen when I tell you how your comments made me feel,” Mehta said.

In her book, Mehta does not directly write about her conversion to Judaism. Rather, the meaning and joy she finds in Jewish tradition, ritual and culture—matzah ball soup is her go-to comfort food—are made clear throughout. And she, too, brings up questions and problems that have arisen during Jewish religious services.

“At the synagogue, treat me like I am a member, a friend of a member or a prospective member,” she said in the Zoom call. During kiddush lunch, for instance, she suggests such conversation openers as asking about a favorite bagel place or the rabbi’s sermon.

The most difficult conversations, Mehta writes, are those with people (as her title suggests) whom she reciprocally loves and cares about—but who also have blind spots about some of their own biases. She acknowledges that such conversation can be challenging, regardless of an individual’s background.

In Jewish communities, however, the fact that we all feel vulnerable to antisemitism can make these talks particularly difficult. “Because Jews experience antisemitism, they can feel that they can’t possibly be doing anything or saying anything that is racist or can be misunderstood that way,” she said. “If you believe in tikkun olam, having someone say you said or did something racist can strike at your sense of self, at your core sense of being a good Jew.”

Rather than walk away hurt, talk through the issues, Mehta encouraged. “I’ve been in conversations where, after a discussion of a misunderstanding, I’ll say, ‘You know, I may have been overly sensitive, I was wrong to call you out.’ And that is fine,” she said, “because you will have a better understanding of each other and cleared the air.”

That hope for better understanding of the experiences and history of our increasingly multicultural Jewish community is the thread that ties together this selection of books. They become a way to investigate assumptions and stereotypes about who and what Jews are and look like.

Mehta suggests in her book to “take it upon yourself to become more open.” Reading about the struggles of women of color with Jewish heritage may help all of us open up and welcome each other into a common fold.

Diane Cole is the author of a memoir, After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges, and writes for The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post and other publications.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

[…] miss Diane Cole’s “Essential Reads: Women of Color Navigating Jewish Identity”(Hadassah magazine). The piece features books by Marra B. Gad, Nhi Aronheim, Laura Arnold Leibman, […]