Arts

Exhibit

A New Exhibit Sheds Light on the Overlooked Women of Sassoon

The Sassoon men cut quite a figure. Their vast wealth, first as opium traders and merchants and later as art patrons and collectors, stretched from Baghdad to Bombay, today called Mumbai, to the royal corridors of Great Britain.

There was patriarch David Sassoon, often pictured in flowing robes with a long silver beard and intricate headdress, every inch a mid-19th-century Iraqi Jew of means. His business empire moved effortlessly between East and West.

There was his son Sassoon David Sassoon, in a smartly tailored black Western business suit in 1858 as he was about to set sail for England, establishing the family’s beachhead in London. Another of his eight sons, Reuben Sassoon, pictured in formal white tie and tailcoat in a Vanity Fair caricature, became ensnared in 1890 in what was known as The Royal Baccarat Scandal, a gambling dispute eventually brought to trial that involved none other than the playboy Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII.

As for the Sassoon women, well, in most accounts of a sweeping family saga that spans from 1830 to the end of World War II, they are largely absent.

A new show about the family at The Jewish Museum in New York City, “The Sassoons,” which runs through August 13, aims in part to fill in those absences, shedding light on overlooked Sassoon women. Among them are businesswoman Flora Sassoon, David’s great-granddaughter, who at age 14 married one of David’s sons; and art collector and patron of poets Mozelle (Gubbay) Sassoon, another of David’s great-granddaughters.

“There is a plaque in the Magen David Synagogue in Mumbai”— built by David in 1864—“with an inscription that offers blessings to all eight of his sons,” Claudia Nahson, the show’s co-curator, said. “Where are the women? The women who gave birth to them and raised them? They are just completely absent.

“And these were really forward-thinking women and pioneers in their own way,” she added. Without them, the family’s story “may have been very different.”

Several generations of Sassoon women are given new life in the exhibit, which charts the female family members’ accomplishments, aesthetic tastes and the friendships they struck up with the personalities of their generations. These include, for example, American expatriate artist John Singer Sargent, who captured the Sassoon family in striking Edwardian-era portraits.

The show opens on the heels of Natalie Livingstone’s recently published history The Women of Rothschild, itself a reassessment of the powerful role played by the women in that dynastic Jewish banking family. (In fact, the “houses” of Sassoon and Rothschild merged in 1887 with the marriage of Aline de Rothschild to Edward Sassoon.)

The Sassoon women are revived as commissioners of exquisite Jewish ritual objects, discerning collectors of sublime 19th-century landscape paintings and expert restorers of grand English manor houses. And they, like their male relatives, cut quite a figure.

In the exhibit, Flora is seen in a photograph from 1900 in Victorian finery. She took the reins of the Mumbai branch of the family business after the death of her husband, Solomon Sassoon—the only Sassoon woman to oversee any part of the company.

It was also Flora who commissioned the wood, silver gilt and enamel round Torah cases, or tikim, that were crafted in China, used in Mumbai and ultimately taken to England. The cases have a prominent place in the show and speak to the continent-spanning reach of the Sassoons.

Another prominent woman in the family was Rachel (Sassoon) Beer, Sassoon David’s daughter. A crusading editor of two British newspapers, she reported extensively on the Dreyfus Affair. She also extended the family’s collecting beyond Judaica and into the realm of fine art. Rachel is seen in the show in Henry Jones Thaddeus’s 1887 portrait, captured in a soft, gauzy light, wearing a delicate silk dress.

And there are cousins representing a generation of Sassoons who came of age in the late 19th and early 20th century. Hannah Gubbay, a Sassoon on both sides, was a sharp-eyed collector of 18th-century porcelain and furniture. According to the exhibition’s catalog, she often roamed country house sales with Queen Mary in tow. Hannah’s cosmopolitan cousin Mozelle was born in 1872 un Mumbai and moved from India to France to England. (Mozelle as well as Flora are frequently used names among the Sassoons.) Her country house in Berkshire had been the home of the celebrated 18th-century English poet Alexander Pope.

As visitors step into the first gallery, they see the portrait of patriarch David Sassoon, painted in tea-colored Baghdadi robes trimmed in scarlet with Mumbai’s Back Bay appearing behind him.

In a nearby gallery hangs a portrait of David’s great-granddaughter Sybil Sassoon. More commonly known as Sybil Cholmondeley, the Marchioness of Cholmondeley, Sargent captured her in a moody charcoal drawing in 1910, pain etched in her young face as she mourned the death of her mother, Aline de Rothschild.

The two portraits, David and Sybil’s, represent an arc of four generations, and they open a window onto a sprawling family journey that hits on many of the central issues that continue to animate the world: global trade, immigration, acculturation, assimilation and antisemitism. David sat for his portrait in India because the family was driven out of Baghdad in 1830 by a campaign of persecution.

“Seeing a story through the lens of a family makes it more personal, more accessible,” Nahson said. “It’s a timely show because of all the subjects it dwells upon, and it’s a timeless story, a story of survival, acculturation, preserving your identity yet adapting.”

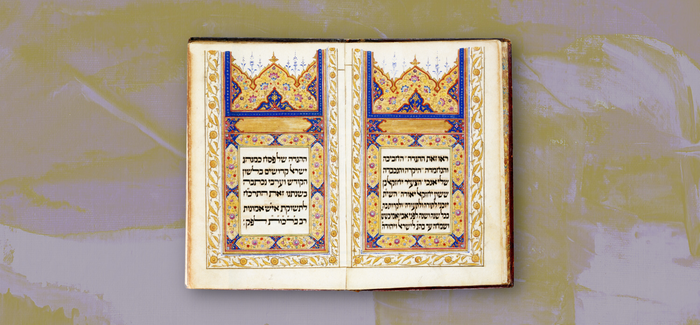

Indeed, the show hinges on the idea that collecting casts a bright light on identity, in all its complex hues. Each graceful Torah finial, lyrical Yuan dynasty handscroll and vibrantly colored illuminated Hebrew manuscript is freighted with emotion, each a kind of way station on the century-long journey of a family lugging its Jewish identity across a fast-changing world.

The things the Sassoon men and women collected, it turns out, were both burden and blessing, pulling them back toward the long gone world of Jewish Baghdad and hurtling them forward into British high society. It was a bittersweet ride—something gained, something lost.

Each city where the family lived “is a passage into something,” Nahson said. “They start as Baghdadi Jews, then they move to India yet still very much with a Baghdadi identity. Then they go to England, and they shut off some of that. As the generations advance, the spiritual and geographical distances are larger, so they integrate what they brought with them.

“But sadly,” Nahson concluded about the wealth and objects collected by the Sassoons, “some of it is gone,” sold at auction and victim to the extended family’s shifting fortunes in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

But not all of it. In a diary entry from 1910, Mozelle Sassoon, Flora’s daughter, writes tenderly of the Torah scroll used during Rosh Hashanah services at the Great Synagogue of Baghdad. It was one of two scrolls encased in ornate tikim, commissioned by her mother, that the family held onto.

“It is contained in a beautiful, chased silver case much tarnished with age,” Mozelle writes.

A century on, those intricately embellished silver cases are on view in “The Sassoons,” perhaps as much a part of the family’s identity as any Sargent portrait.

Robert Goldblum is a writer living in New York City.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply