Israeli Scene

Feature

Israeli Companies Seek to Transform Women’s Health Care

When the women behind the Israeli medical startup OCON Healthcare set out to improve upon a popular form of contraception, they were trying to solve for a problem most investors in Israeli technology—men, that is—didn’t even know existed. In the process, they also ended up creating a device that may help women suffering from a whole host of gynecological conditions.

Millions of women worldwide rely on intrauterine contraceptive devices, or IUDs, for preventing pregnancy. The T-shaped contraceptives use either copper, which is wrapped around the device, or hormones to prevent sperm motility and implantation. A health care professional inserts the IUD into a woman’s uterus, where it remains effective for several years, obviating the need for pills, sterilization or other forms of birth control.

But IUDs have problems. They’re made of molded plastic and sometimes break. They don’t always fit correctly in the uterus cavity, leading them to shift out of position or even be expelled from the vagina. And about 1 in 1,000 women experience a perforation when the device is inserted.

“Women were suffering, women were in pain, but the IUD was ‘good enough,’ ” said Keren Leshem, CEO of OCON, based in the central Israeli city of Modiin. “Men didn’t see the opportunities in this space.”

It took a female-led team of Israeli scientists and professionals with experience in pharmaceuticals and drug development to arrive at a unique solution: a ball-shaped device they called an IUB, or intrauterine ball, formed from strings of a super-elastic alloy. For birth control, it uses the same material of traditional non-hormonal IUDs—copper, in the shape of beads strung along the ball. But this new design is less than half the size of standard IUDs, can be inserted with greater ease and conforms to the shape of female anatomy, minimizing the risk of irritation or damage.

OCON began selling its product, called the IUB Ballerine, about two years ago. It’s now in use by more than 120,000 women in Israel, Europe and South Africa. Working off that success, OCON is devising ways to use its IUB as a platform for delivery of drugs to the uterus to help treat conditions such as abnormal menstrual bleeding, endometriosis and uterine fibroids. Depending on the use, the ball-like delivery device is the same but the active ingredient—a drug-eluting bead placed on the ball itself—is different.

“While contraception is a large market, there are still many underserved, untreated indications that don’t have a solution,” said Leshem, whose company is currently raising $25 million in investment to support the clinical and application process in the United States, including U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for contraceptive use. “Oral hormones and therapeutics can cause huge side effects. Our vision is to take these oral treatments, put them on the ball and deliver them to the target tissue, which would require a much lower dose of medicine. We’re building the first dedicated uterine-friendly platform to treat pathologies in and around the uterus.”

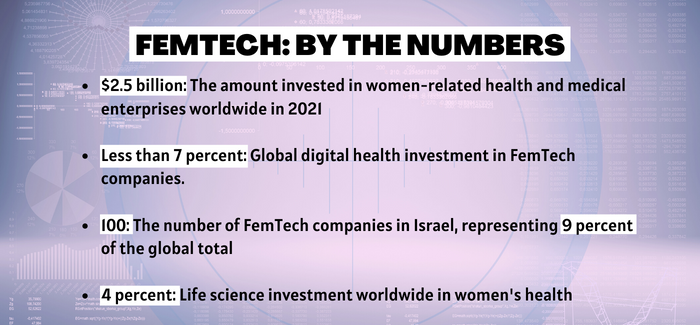

OCON, recognized at the World Economic Forum in Davos this year as one of 100 global “Technology Pioneers,” is a prominent example of Israel’s growing dominance in FemTech: companies that use technology to reimagine and innovate women’s health care in areas such as fertility, menopause and wellness. Israel has approximately 100 FemTech companies—an astonishing 9 percent of the global total, according to Dr. Benny Zeevi, a pediatric cardiologist and venture capitalist investor who founded and organized a Women’s Health Innovations and Inventions summit in Israel earlier this year.

There’s no universal definition of what constitutes FemTech, and the term itself is more colloquial than scientific. Companies in this area may work on everything from manufacturing medical or gynecological devices, like the IUB, to designing AI-powered digital health apps, such as those from Healthy.io that can diagnosis a urinary tract infection via smartphone. FemTech businesses are often but not always led by women.

“FemTech, from my perspective, is a combination of several disciplines, from high tech to cyber, cloud computing and all the life sciences, plus medical devices, pharmaceuticals, biotech, diagnostics and health technologies,” said Karin Mayer Rubinstein, CEO of Israel Advanced Technology Industries (IATI), the nonprofit umbrella organization that advances Israel’s high-tech and life-sciences industries. “FemTech has caught on because the whole world has changed: The pandemic gave a big push to digital health.”

Israel’s strong position in this emerging field is a reflection not just of the country’s well-documented high-tech prowess, but also of its position as the world’s per capita leader in IVF, in vitro fertilization. Many of these companies work in fields related to IVF.

The global market for FemTech is expanding rapidly. In 2021, about $2.5 billion was invested in women-related health and medical enterprises worldwide, nearly double the total of 2019, according to a recent report by McKinsey & Company. Despite this, funding for FemTech companies represents less than 7 percent of global investment in digital health overall. Investments in research and development for women’s health in general, excluding cancer, represent just 1 percent of all R&D investment, according to McKinsey.

“We’re actually not investing a lot in women’s health even though the disease burden is high,” said Gila Tolub, the Israel-based author of the McKinsey report. Women’s diseases impose a significant burden on women’s productivity, longevity and well-being as well as a heavy financial toll on both women and the economy, according to Tolub.

“Women’s health is viewed as a niche problem,” she added.

Nevertheless, in Israel, there’s no shortage of FemTech startups.

Illumigyn, a company based in Neve Ilan near Jerusalem, has developed an FDA-approved gynecological scope that seeks to improve upon traditional pap smears by generating high-resolution digital images of a woman’s cervix, vagina and other genital areas. Physicians can analyze the images remotely to screen for cervical cancer and other issues. Founded by entrepreneur Ran Poliakine and medical device creator Lior Greenstein (both men), Illumigyn this year began selling its device in several countries, including Israel.

Tel Aviv-based AIVF, founded and headed by clinical embryologist Daniella Gilboa, uses artificial intelligence (AI) to guide the embryo selection process when retrieving and choosing eggs for fertilization. In June, AIVF completed a $25 million investment round to expand the use of its main software platform, called EMA, an acronym for Embryology Management Assistant—and the Hebrew word for mother.

And a Jerusalem-area business led by biochemical engineer Hilla Shaviv, Gals Bio, has developed a product—the Tulipon—meant to combine the benefits of a tampon with those of a menstrual cup by catching and collecting menstrual blood. Made of a disposable biopolymer, the Tulipon opens like a cup when inserted into the body and is designed to provide leak-proof protection even during heavy bleeding.

If you’re a woman reading about such innovations for the first time, you may find yourself excited by their prospects. But many men listening to investment pitches from early stage FemTech startups react very differently. And therein lies one of the main challenges.

“Most of the investors are men, and they’re not aware of women’s problems and they don’t understand the potential of the women’s health market,” said Dr. Zeevi, the venture capitalist. “You start to talk to them about vaginas and menstruation and they turn away. They sink down in their chairs and begin to look at their phones.”

“Women,” he continued, “constitute 50 percent of the population and do 90 percent of the health spending in their families, yet women’s health is still considered a niche. Only 4 percent of investments in life science is in women’s health.”

As a consequence, a large number of FemTech companies in Israel rely on crowdfunding or other alternative investment methods.

Hadassah gynecologist Dr. Ahinoam Lev-Sagie co-founded GynTools to diagnose a variety of vaginal conditions that often go misdiagnosed or undiagnosed, leading to months or even years of discomfort, painful sex or illness. Dr. Lev-Sagie’s device, Gyni, is a diagnostic tool that uses AI to accurately determine the results of a vaginal swab in real time. By correctly identifying the problem during an exam, health care practitioners can provide the appropriate treatment rather than offer one-size-fits-all creams or antibiotics. The device has been approved for use in Europe and is in the process of getting Israeli approval, with the United States the company’s next target, according to Dr. Lev-Sagie.

However, raising the $5 million needed to improve the product’s AI algorithm, market it and fund the FDA-required research process has been arduous. The $2.8 million raised so far has come from the Israel Innovation Authority, private investors and Dr. Lev-Sagie’s family. Her brother and co-founder, Nimrod Lev, a mechanical engineer, built the device, and her husband, Meny, a computer programmer, designed the algorithm it uses.

“We come with our device, and male investors say, ‘Why do you have to understand her problem? Just give her an anti-fungal cream,’ ” Dr. Lev-Sagie said.

Despite the difficulty raising funds, Israel is a very nurturing place for these startups, according to Tolub of McKinsey.

“What I love about FemTech in Israel is it’s a very collaborative environment. Everyone seems motivated by one purpose, and it’s almost as if they don’t see themselves as competing with each other,” Tolub said. “We have a WhatsApp group with all the CEOs in women’s health. They help each other, they share the names of investors, they don’t try to hoard the information.”

A number of Israeli leaders in FemTeh have already made it big. In addition to OCON, Healthy.io, founded in 2013 by Israeli entrepreneur Yonatan Adiri, uses smartphone technology and cloud computing for remote imaging and diagnosis. The service, which uses a phone’s camera as well as an at-home urinalysis kit, works for pregnancy-related complications as well as a screener for urinary tract infections and chronic kidney disease. The company’s app-based services are used widely, including in the United States.

Israeli-incubated Pulsenmore, founded in 2014, created a device for pregnant women to scan their own ultrasounds at home, using a cradle that attaches to a mobile phone. The company has gone public and is traded on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange at a valuation of about $160 million. GE Healthcare recently announced a $50 million investment in Pulsenmore.

What’s missing in Israel isn’t success stories, but a funding framework to help fledgling entrepreneurs turn promising ideas into promising companies, said Sharon Rashi-Elkeles, founder of a now-defunct Israeli FemTech hub called Eve. Rashi-Elkeles launched the hub in 2018 with a vision of providing mentoring, support and a modest pool of money that entrepreneurs could access. But funding from companies and governmental bodies that support other high-tech hubs—cybersecurity, for example—never materialized.

“There are so many accelerators and hubs and frameworks to push Israeli startups forward,” Rashi-Elkeles said, “but when it comes time to give money to FemTech, it doesn’t happen.”

The problem goes beyond money. For decades, women have been given short shrift when it comes to health care research and treatment protocols. In the United States, women were excluded from most clinical research and drug trials into the 1990s, even though women react differently than men to many of the same treatments and illnesses. (For example, heart attacks have different symptoms in women than in men.) And, of course, health care issues specific to women, such as menopause, tend to be understudied and undertreated.

“Awareness of the importance of separating out women’s health as its own specific field is still missing,” said Sari Prutchi Sagiv, vice president of R&D at Gynica, an Israeli startup developing cannabinoid-based gels and suppositories for problems such as painful menstruation and uncomfortable sex.

“In women’s health, generally, there is a large unmet need,” she added. “I think there’s a lot of awakening, but more money needs to be found to create solutions for women’s health.”

Uriel Heilman is a journalist living in Israel. He works for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency‘s parent organization, 70 Faces Media.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

serge kurilov says

Great article! I’ll spread it through my contacts.

God bless Holly Land and Jewish folks with such brain power and creativity.