Books

Non-fiction

The Unsung ‘Women of Rothschild’

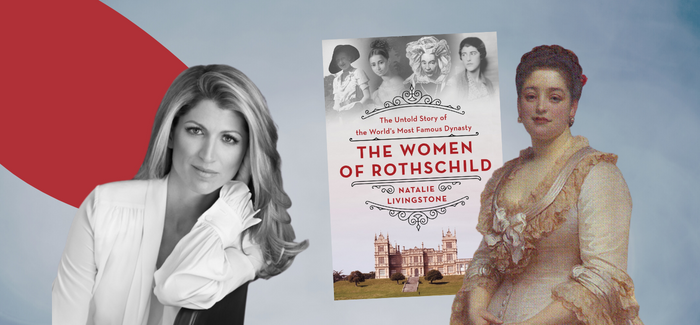

The Women of Rothschild

by Natalie Livingstone (St. Martin’s Press)

An inspiring account of a family that, despite immense wealth and power through multiple generations, largely did not forget their roots, The Women of Rothschild is an exceptional work of scholarship. Spanning roughly two-and-a-half centuries, the book is filled with illuminating anecdotes and details—clothing, grand homes, art and politics—about the unsung women of the illustrious Jewish family whose financial prowess and influence is not only legendary but also the fodder of antisemitic conspiracy theories.

The Rothschild banking dynasty was founded in Frankfurt by Mayer Amschel Rothschild in the 1760s. He had five sons, each of whom he assigned a territory—Vienna, Paris, Naples, Frankfurt and London. But there was a stipulation in “the will of the bank’s founder [that] explicitly forbade his female descendants”—including his five daughters—or the wives of any male descendants from having any shares in the bank’s business or say in its decision-making process, writes author Natalie Livingstone.

But despite these restrictions, as it becomes clear in the book, it was the women who by force of their intelligence, strength and perseverance led their families to new heights. Livingstone does an exemplary job of sharing their stories, starting with Mayer’s wife, Gutle, who fielded questions from the police during the Napoleonic occupation and hired a philosopher, a disciple of Moses Mendelssohn, to educate her children.

Livingstone also describes how Nathan, the founder of the bank’s British branch, found a way to grant his wife some authority after his death. He stipulated in his will “that when his sons voted as sub-partners, they were also bound to give weight to (their mother) Hannah’s opinions.”

“Quietly, tactically, and in a way that likely went unnoticed by his own brothers,” Livingstone writes, “Nathan had smuggled the opinion of his wife into the decision-making structure of the family business.”

For the most part, Livingstone limited her research to this British branch of the family, considered among the most successful. Today, it is headed by Nathaniel Charles Jacob Rothschild, the fourth Baron Rothschild, who goes by the name Jacob. Even here there was a lot to cover, so much so that it is occasionally difficult to keep track of the daughters, wives and cousins. That’s complicated even further because cousins frequently intermarried and offspring received the names of deceased relatives. There are a lot of Hannahs, Louisas and Charlottes.

Among the achievements of later generations, Louisa de Rothschild was instrumental in funding the Jews’ Free School for residents of London’s impoverished Jewish population. In the mid-19th century, Emma Rothschild offered workers on her estate medical care for a one-pound annual fee. Miriam Rothschild became a respected natural scientist and world expert on, of all things, fleas; in 2000, she was made a Dame of the British Empire for services to nature conservation and biochemical research.

The family was split on Israel. Most, however, supported the efforts to build the Jewish state. They funded projects and settlements across pre-State Israel, including Zichron Yaakov and Rishon LeZion. Indeed, it was a Rothschild who funded construction of the Knesset building.

Livingstone’s extensive research and journalistic skills bring many of these extraordinary women to life.

Curt Schleier, a freelance writer, teaches business writing to corporate executives.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply