Being Jewish

Feature

One Woman’s Crusade to Aid Syrian Refugees

Georgette Bennett holds up a yellow Star of David in a simple 5×7 picture frame. The Nazi-era patch emblazoned with the word “Jude” belonged to a cousin, one of Bennett’s few relatives to survive the Holocaust.

“I keep this visible at all times on a ledge by my desk,” she says, sitting in the library of her spacious Manhattan apartment. “It reminds me of why I do what I do.”

What Bennett does is counter hate, build bridges and aid and rescue others through humanitarian diplomacy. A master of people-to-people connections, she includes among her many careers author, sociologist, journalist and professor. She has corralled governments, organizations, entrepreneurs and donors to help people in need. She has crisscrossed the globe to raise awareness and funds, meeting with cardinals at the Vatican, representatives of the European Union in Brussels, Jewish funders in Miami, humanitarian activists in Israel and many others.

Her activism is deeply personal. As a toddler, she fled with her parents from her native Budapest to France and then, at the age of 5, to Queens, N.Y. Today, at 75, she has turned her personal calling into a crusade to alleviate the devastation of Syrian war victims caught in their nation’s ongoing civil war. Of the world’s 89 million displaced people, over 6 million are legally registered Syrian refugees, a number that has just recently been surpassed by the 7.7 million Ukrainian refugees. Many more Syrian refugees are unregistered.

In 2013, Bennett founded the Multifaith Alliance for Syrian Refugees (MFA), a nonprofit with more than 100 partner organizations, including the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the Anti-Defamation League, IsraAID, Episcopal Migration Ministries and the Syrian American Council. MFA focuses on delivering humanitarian aid, food and medical supplies to hard-to-access parts of Syria. The alliance also advocates for more refugee admissions and “humane and rational” policies toward refugees and displaced persons in the United States and other countries. To date, MFA has provided close to $260 million in aid, from governments, organizations and private donors, benefiting more than 2.7 million Syrian war victims, most of whom are in Syria but also some in Iraq and Lebanon.

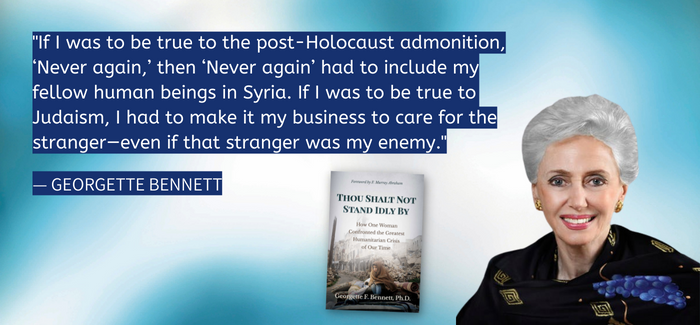

“If I was to be true to the post-Holocaust admonition, ‘Never again,’ then ‘Never again’ had to include my fellow human beings in Syria. If I was to be true to Judaism, I had to make it my business to care for the stranger—even if that stranger was my enemy,” Bennett writes in Thou Shalt Not Stand Idly By: How One Woman Confronted the Greatest Humanitarian Crisis of Our Time. Her recent memoir chronicles both the 11-year crisis in Syria as well as her mission to provide aid.

Bennett has been widely recognized for her efforts. Among her many awards, Forbes last year named her to its first “50 Over 50 Impact List” and AARP awarded her its 2019 Purpose Prize for “tapping into the power of life experience to build a better future for us all.”

Bennett’s expansive apartment with its panoramic views of Central Park is a vast change from the home in which she grew up as a poor immigrant in the Kew Gardens section of Queens. “I never take for granted the good fortune I’ve had,” she says. “It’s a terrible cliché, this idea of giving back, but it’s very real for me.”

Photos of her family line the windowsill of the library. The photos include many with her British husband, Leonard Polonsky CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire), who was granted the highest-ranking award before knighthood for his charitable work; her son Joshua-Marc Tanenbaum, 30, an investment banker at Citigroup, from her second marriage to the late Rabbi Marc Tanenbaum; her three stepchildren; five step-grandchildren and two step-great-grandchildren. (Her first marriage ended in divorce. Polonsky and Bennett also have homes in Westchester County, N.Y., and London.)

Elegant in a navy silk-crepe blouse and matching jacquard-patterned jeans, Bennett’s white hair is swept away from her face, highlighting a beaded navy necklace and earrings that pick up the azure of her eyes. She is barefoot, as she often is at home. Her mother, a successful lingerie designer, influenced her sense of style, she says. She still keeps some of her mother’s pieces in the soiled and battered beige suitcase her family brought to the United States, a reminder of her journey from stateless displacement to safe haven.

In addition to her refugee work, the improbable partnerships that Bennett helped craft between Israelis and Syrians, mostly sworn enemies, are among her most notable achievements. Beginning in 2014, her maneuvering helped create a channel in the Golan Heights that allowed food, medical supplies and other aid to be delivered to the area of southwest Syria that was surrounded by President Bashar al-Assad’s forces. The Israel Defense Forces, which had already been providing medical treatment for injured and sick Syrians who showed up at the border, officially launched Operation Good Neighbor in 2016 and expanded the mission by partnering with MFA to get humanitarian aid directly into Syria.

When that Golan Heights channel closed in 2018 because of a deconfliction agreement between Russia, Iran, Turkey and Israel, MFA rerouted deliveries to northern Syria, through Turkey and Iraq, where it continues to operate today.

One of the ongoing recipients of MFA aid is the Women’s Relief Program, which distributes chemotherapy drugs for breast cancer patients, estrogen medication, personal safety whistles, menstrual supplies and ob-gyn equipment to medical facilities and mobile clinics in northern Syria and Iraq.

conversing with the late Israeli Prime Minister Simon Peres (left) in 2013.

Over the years, Bennett has seized every opportunity to network with those who can advance her cause. At a 90th birthday party for the late Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres that she attended in 2013, she watched a video that featured a greeting from a mysterious Syrian refugee. Though his face was blurred intentionally to protect him, Bennett was so moved by his words that she was determined to find him. And she did.

That refugee, Shadi Martini, the scion of a prominent Syrian family, was a former hospital administrator in Aleppo who was forced to flee to Bulgaria after his network for aiding injured civilians was discovered. He accepted Bennett’s invitation to address a 2014 Jewish Funders Network conference in Miami. Soon after, he became an integral part of her work. His knowledge of the situation on the ground in Syria and his extensive contacts enabled Bennett to penetrate circles to which she would not otherwise have had access. Today, he is MFA’s executive director, based in New York City.

Martini describes Bennett as “honest, compassionate and hardworking.” As a Muslim growing up in Syria, he says he was inculcated with a lot of “bigotry against the Jewish faith. Georgette knew a lot more about Islam than I knew about Judaism. For me it was a learning curve and an eye-opener to see how much Muslims and Jews have in common.”

Bennett’s memoir not only showcases her networking genius but also her formula for success: Find an entry point and a gap that no one has addressed and stay tightly focused on what’s doable rather than the totality of the problem.

who had fled Bulgaria, to join her cause. Today, they co-lead MFA.

In the case of Syrian refugees, she first mobilized the Jewish community through the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, which brought together 16 Jewish organizations to form the Jewish Coalition for Syrian Refugees in Jordan, which raised money for organizations already involved in aiding victims of the war. In fact, the creation of the MFA was an outgrowth of what started as a Jewish initiative, she writes in her memoir. Then, she catalyzed a positive response from Israel, partnering with the IDF to allow aid through the Golan Heights.

“If you focus on the big picture in any of these overwhelming crises you just get paralyzed into inaction. If all you feel is helplessness, then you can’t do anything to repair the world,” she says. “I can’t tell you how many people have asked me, ‘What are you doing about Ukraine?’ I’m writing personal checks, but I need to stay focused on the Syrians.”

Bennett says all her work stems from her longstanding desire to always “get behind the headlines and go where the action is.” With a Ph.D. in sociology from New York University and an advanced degree in banking from the Stonier Graduate School of Banking at the University of Delaware, she embarked on a diverse career spanning criminology, marketing, teaching, broadcast journalism, philanthropy, conflict resolution and interfaith relations.

In the 1970s, Bennett headed New York City’s Criminal Justice Task Force, pioneering the first federally funded crime victim service center, where she coordinated the training and evaluation program for the city’s police department. Her journalism career included stints as a correspondent for NBC News television and radio and as consultant and writer for ABC’s 20/20, CBS’s 60 Minutes and PBS’s MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour. She has authored six books and over 50 articles.

In her 1987 Crimewarps: The Future of Crime in America, which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, Bennett predicted that cybercrime and white-collar crime would be a major threat and wrote about the link between religious extremism and violence. After publishing her memoir, her next book, Religicide: Confronting the Roots of Anti-Religious Violence, due to be published in November and co-authored with social entrepreneur and activist Jerry White, proposes a new legal category of atrocity—religion-based violence—that currently falls through the gaps in international law.

Bennett first read about the Syrian crisis in a 2013 report from the International Rescue Committee (IRC), that had sat unopened on her desk for five months. Her late husband, Tanenbaum, a human rights activist who pioneered numerous multifaith coalitions, had served for 25 years on the IRC’s executive committee, where he organized rescue operations, for, among other groups, the Vietnamese “Boat People” and Cambodian refugees. Deeply influenced by his work, Bennett joined the IRC board after his death in 1992.

When she finally read the report, she says, she was appalled by the “unspeakable horror” the Syrians were fleeing—torture, civilian bombings, mass displacement, sexual violence and starvation. Massive amounts of aid were coming into Syria via the United Nations and other channels, but Assad’s regime controlled its distribution, diverting the aid to supporters or selling it for profit.

“And the silence of the world was deafening,” Bennett writes in Thou Shalt Not Stand Idly By. “I felt commanded to act.” More than 80 percent of those displaced by the war were women and children, who were left squatting wherever they could find shelter. Many were repeatedly raped, according to the IRC report. “It was the gender violence that gripped me and wouldn’t let go,” she writes, revealing in her book that she herself survived a sexual assault at the age of 18.

Bennett considers herself “a very serious Jew,” committed to the values of tikkun olam and helping the stranger. She is not observant, but she belongs to B’nai Jeshurun and Park Avenue Synagogue, both in Manhattan. Her childhood spurred her early interest in religion. Her father, Ignatz Beitscher, died at age 52 of cancer, a year after they had immigrated to Queens. A kind Christian Scientist neighbor took the new immigrants under her wing: Bennett attended Sunday school with her daughter, and at summer camp, performed with a choir at churches throughout New England. As a teenager, she went to Hebrew school for a year and sometimes attended Shabbat services.

When Tanenbaum passed away at age 66 of complications from open-heart surgery, Bennett was 45 and eight months pregnant with their only child. Four months after Joshua-Marc was born, Bennett founded the Tanenbaum Center for Interreligious Understanding to combat religious prejudice and violence in schools, workplaces, health care settings and areas of armed conflict. She is still the president of the group.

Bennett inherited a legacy of harrowing loss and intrepid rescue from her parents. Her father’s first wife and two children were shot in front of him during selections in the Tarnow Ghetto in Poland. Ignatz Beitscher and his sister escaped to Budapest and met Sidonie, who gave them shelter. A year and a half later, before Sidonie and Ignatz married, a neighbor reported blonde, blue-eyed Sidonie, who was passing as a non-Jew, for hiding Jews. She was sent to prison—the same prison as resistance fighter Hannah Szenes, who was awaiting execution, and Szenes’s mother. There, Sidonie passed messages between the mother and daughter. Sidonie was then sent to a Hungarian concentration camp, Kistarcsa. Bennett recounts in her book the dramatic story of how Ignatz rescued his soon-to-be wife after killing a German solider and stealing his uniform, and how they made their way from Budapest to Paris.

Sponsored by a relative, the family was then able to immigrate to New York. When Sidonie applied for citizenship 10 years after Ignatz’s death, she tasked Georgette with choosing a new last name devoid of anything that sounded German like their original name, Beitscher. “I went to the Queens phone book and narrowed it down to Bentley, Bender and Bennett,” she recalls. A classy neighborhood dress shop called Sylvia Bennett clinched her decision.

“I’ve always asked myself if I would have had the courage to do the things my parents did. I’ve always put myself in situations where I’ve had to test myself,” Bennett says. “Earlier in my life, it was driving too fast. I loved horror movies because I needed to see how I dealt with fear. The older I got, the more of a coward I became. I realized I had so much to live for.”

Bennett’s friend of 47 years, Andrea Berger, an attorney for New York City, describes her as the most extraordinary person she’s ever met. “She is brilliant, exuberant, fearless, unfailingly generous, creative and visionary,” Berger says. “Her rare combination of personality traits and her ability to network has allowed her to do things that have a real impact on the world. And she does it all with dignity and poise.”

There appears to be no end in sight for Bennett’s activity and list of projects. To give her brain a rest from all her work, she says, she watches a lot of television dramas and reads thrillers and whodunits. She intends to resume playing the piano, which she did competitively as a teenager.

Bennett treasures a plaque that is displayed prominently in her study, a gift from retired IDF Major General Yoav “Poly” Mordechai, a key player in the Israeli-Syrian negotiations. Inscribed on the plaque are the words from the Talmud: “Whoever saves a life, it is considered as if he saved an entire world.” Mordechai added his own inscription: “Thank you for your contribution to bringing light into darkness.”

Looking at the plaque always bring tears to Bennett’s eyes. “It’s my reminder,” she says, “that one person can do something real to alleviate massive suffering.”

Rahel Musleah leads virtual tours of Jewish India and other cultural events and has scheduled her first post-pandemic, in-person tour for November 2022.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply