Arts

Feature

The Rebirth of Philadelphia’s American Jewish History Museum

“YO!” shouts the 8-foot-high yellow sculpture of the two letters standing outside the newly reopened Weitzman National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia. “OY!” it groans when viewed in reverse, as visitors snaps selfies alongside Brooklyn-based artist Deborah Kass’s wry nod to the intermingling of different cultures in urban America. The Yiddish “oy” is that favorite expression of dismay, while “yo,” a common slang greeting that also means “I” in Spanish, may bring to mind the city’s famous fictional son, boxer Rocky Balboa, yelling “Yo, Adrian!” in the first Rocky movie.

Kass’s piece, a hit in numerous cities, will spend a year in Philadelphia—just one example of how the newly reopened museum is engaging with a very different America than the one to which it had closed its doors in 2020.

“Our challenge was to take account of what we have all been living through these past two years,” CEO Misha Galperin said, referring not only to the pandemic and America’s racial reckoning, but also the rise in antisemitism.

He might as well have been referencing the museum’s own journey to insolvency and back. The museum filed for bankruptcy in March 2020 and shut down weeks later for the Covid pandemic, furloughing much of its staff. Many feared the national showcase for the story of American Jewish success might succumb to failure.

But in May 2022—Jewish American Heritage Month—the Weitzman National Museum of American Jewish History reopened with a new name and a clean balance sheet, thanks to the generosity of supporters.

The museum’s core exhibition and permanent galleries still illuminate the American Jewish story, from colonial-era Sephardi pioneers to 20th-century heroes like Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis and Hadassah founder Henrietta Szold. And on display through December is “The Future Will Follow the Past,” from artist Jonathan Horowitz. The installation of works—some his own, others by noted artists who are both Jewish and non-Jewish—explores the social issues this country has wrestled with since 2020 and their relationship to the American Jewish experience.

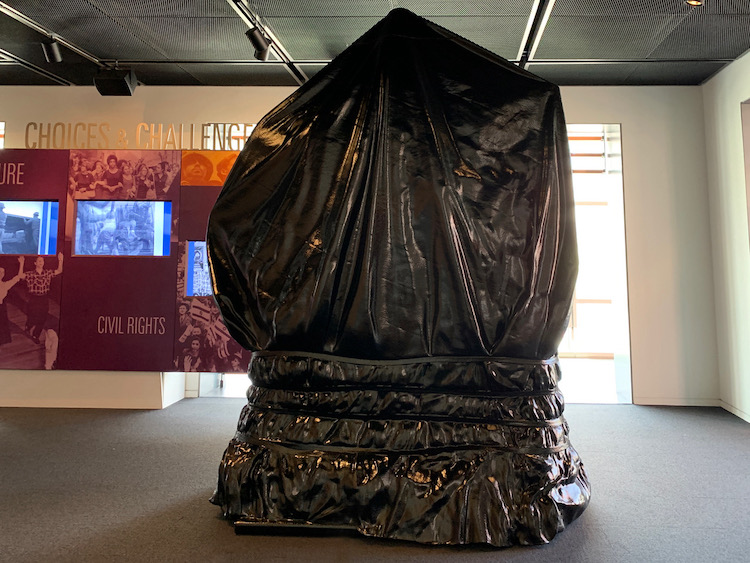

Both racism and antisemitism figure in Horowitz’s large-scale work “Untitled (August 23, 2017-February 18, 2018, Charlottesville, VA),” a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee draped in a black tarp. It references the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, ostensibly gathered to protest the proposed removal of a statue of Lee and where protestors chanted “Jews will not replace us.”

In a similar melding of Jewish and contemporary concerns, the Stars and Stripes that represented freedom for European Jewish refugees get a rainbow-glitter makeover—an LGBTQ symbol—in Horowitz’s “Rainbow American Flag for Jasper in the Style of the Artist’s Boyfriend.” The piece references pop-artist Jasper Johns’ famous series of flag paintings as well as the glittery artistic style of conceptual artist Rob Pruitt, who is Horowitz’s partner.

With exhibits like these, the renewed museum trains a Jewish lens on the age-old idea of American freedom—not only the museum’s explicit theme, but also that of Philadelphia’s Independence Mall just outside.

Many Americans, noted Emily August, the museum’s chief public engagement officer, “can relate to a minority immigrant group navigating the opportunities and challenges of New World freedom.”

Fittingly, the museum was itself founded in 1976 by members of Philadelphia’s Congregation Mikveh Israel, which was founded around 1740. Decades later, having secured a space on Independence Mall, the institution took on substantial debt to finance the 100,000-square-foot glass edifice designed by James Stewart Polshek of Polshek Partnership (now Ennead Architects).

With balconies overlooking the National Constitution Center, the museum, with a $150 million price tag, instantly became a Philadelphia landmark when it opened in 2010. Tourists and school groups marveled at the world’s largest collection of Jewish Americana. Locals embraced the building as a fixture of cultural life. The museum hosted annual Passover seders, Hanukkah parties and cocktail parties, and the much-lauded gift shop was a Judaica destination in itself.

Bankruptcy came as a shock to many. While the museum generated enough revenue to support operations, its remaining $30 million debt burden had become so untenable that the board decided Chapter 11 was “the best chance to resolve the issue while continuing to operate,” said August.

During the pandemic shutdown, the bankruptcy filing rendered the museum ineligible for the government aid that sustained other cultural organizations through prolonged closures. The museum was forced to downsize, pivoting to online exhibitions.

In September 2021, longtime museum benefactor Mitch Morgan bought the building for about $10 million, leasing it to the museum for a nominal $1,000 a month as it emerged from Chapter 11. That December, celebrated shoe designer and Jewish philanthropist Stuart Weitzman donated what museum officials will only identify as “an eight-figure gift,” allowing the museum to buy back its building from Morgan and create an endowment.

“It sounds cheesy, but it was like our own Hanukkah miracle,” August said.

A new free-entry policy, subsidized by donors, “invites people of all backgrounds to think about how our story connects to their own stories,” she observed, “which is increasingly important as our society becomes more divided.”

One new exhibit with artifacts from last January’s synagogue hostage crisis at Congregation Beth Israel in Colleyville, Texas, encapsulates those tensions and divisions. There’s the teacup with which Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker welcomed a British-Pakistani stranger to the congregation—and the chair the rabbi later threw to escape that stranger, who, in yet another example of rising antisemitism, turned out to be a hostage-taker.

The Colleyville synagogue story is, like so many American Jewish accounts of challenge and triumph, an important piece of shared heritage.

Now that the repository of those stories is back in business, August said, “we want to shout it from the rooftops.”

Hilary Danailova writes about travel, culture, politics and lifestyle for numerous publications.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply