Health + Medicine

Feature

The Journey From Loss to Healing

On October 5, the Day of Atonement, I will join Jews all over the world in reciting Yizkor prayers in remembrance of those we’ve lost. It will be the 41st time I’ve said these prayers for my father, the most important man in my life. He took me to parades and double-feature movies in two different theaters on the same afternoon. He instilled in me a love of books and language and a duty to give back to my community. He taught me to stand up straight.

I’ve recited Yizkor 17 times for my mother, and I still want to call her every time I come home from a trip to report that I’ve returned safely. And for the last 12 years, I’ve prayed for my beloved baby sister. We had vowed to spend our old age in the same nursing home, side-by-side in our rocking chairs, but breast cancer prevented her from keeping her end of the bargain.

Even after all these years, when the service ends, I will once again be sobbing into my very wet handkerchief, still surprised at how I can be overwhelmed by grief. How true it is that death ends a life, but it does not end a relationship.

These last few pandemic years have draped the entire world in a black cloak of mourning. The emotional toll of Covid, gun violence, the war in Ukraine and tumultuous politics have all contributed to the proliferation of discussions about loss and grief. At the same time, many gifted writers—quite a number of them Jewish—are turning inward to plumb the depths of loss, particularly personal loss. I spoke with three of them as well as a few friends about their different journeys from grief to healing.

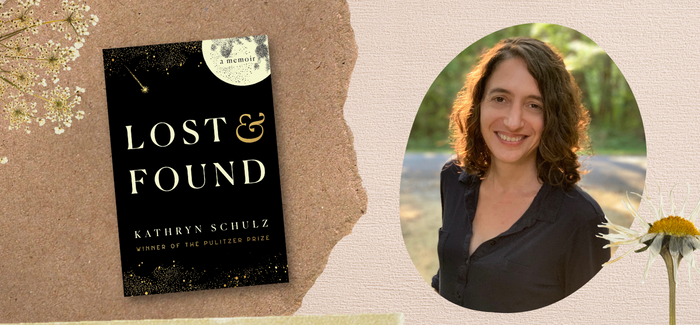

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author Kathryn Schulz builds her exquisite new memoir, Lost & Found, on the passing in 2016 of her beloved father, Isaac Schulz, a man she describes in the book as “part Socrates and part Tevye” as well as on her finding a new love that dropped serendipitously into her life.

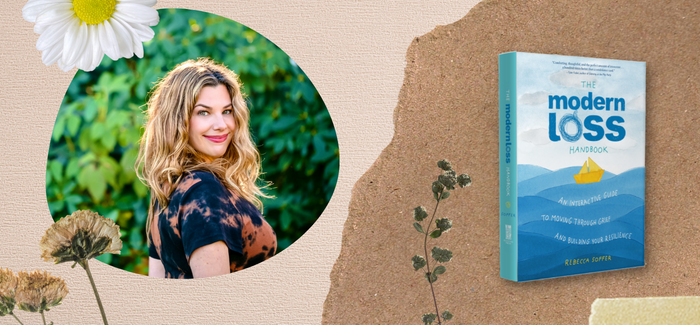

Rebecca Soffer is CEO and co-founder of Modern Loss, an online community for those dealing with grief, and author of The Modern Loss Handbook: An Interactive Guide to Moving Through Grief and Building Your Resilience. She says she wrote the guidebook that she wished she had had over a decade ago, when both her parents died before her 35th birthday—her mother in a car accident and her father of a heart attack just four years later.

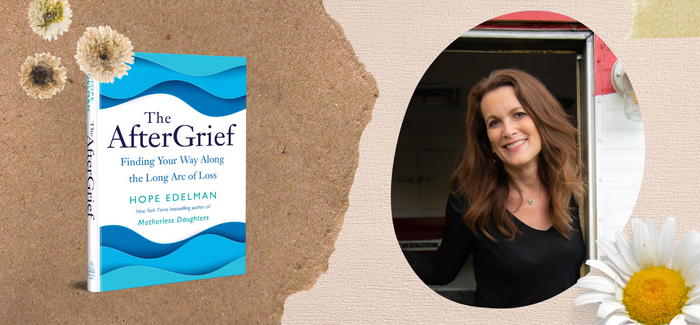

Hope Edelman was 17 when cancer took her mother, which led to her writing her first book, Motherless Daughters, a No. 1 New York Times best seller. The realization that her grief was still sewn into the fabric of her life produced her latest work, The AfterGrief: Finding Your Way Along the Long Arc of Grief.

Grief, these writers note, is a universal experience. But grieving is uniquely personal and idiosyncratic. We can’t turn to science for guidelines. “Each person’s grief is as distinctive as their thumbprint,” Edelman said in an interview.

For her part, Schulz debunks the myth that there are normal stages of grieving. “Grief,” she told me, “is made in the shape of the person you lost. It depends on the nature of your relationship.” In early grief, for example, you might be purely, deeply sad, or angry or awash in disappointment, nursing old hurts and unresolved guilt.

“I was surprised to learn that allowing these awful, horrible, no-good feelings have their way with me was exactly what allowed them, over time, to start diminishing,” Edelman writes in The AfterGrief. “Only through surrender did I regain my power.”

Anger resonated deeply for a friend of mine whose bright, graduate-school-bound granddaughter died of a drug overdose during a weekend of casual partying. “For a long time, I was furious at everything,” said told me. ”At her for dying, at the world for allowing such an unnecessary loss, at the sun for rising every morning.”

While every culture has its own rites of mourning, the Jewish ritual of shiva, which includes seven days of calls and visits from friends and acquaintances, is often singled out as among the most helpful in transitioning from the mind-numbing burial to the long and tortuous road of grieving.

Unfortunately, loss puts many people at a loss for what to say during these visits to the bereaved, who in the depths of mourning can’t believe they won’t always feel as awful as they do right now. The last thing they want to hear are platitudes that are more likely to offend than comfort: Life goes on; everything happens for a reason; you can’t live in the past; at least so and so is in peace and gone to a better place.

Sue Rubel, a successful interior designer in Philadelphia, still shudders 44 years later when she recalls the stinging words of an elderly woman who attended the shiva for her husband, Rick, who tragically died at age 50 when he was drawn into the wind force of a speeding tractor trailer while changing a flat tire on the shoulder of a busy highway. “She grabbed my cheeks and rocked me back and forth screeching, ‘Oy vey. Oy Vey. Oy vey. Welcome to the widow’s club.’ ”

“Mourners don’t need advice and wisdom,” said Schulz. They need help: Run an errand or drop off a meal or some cookies. Invite them out for a walk. Give them attentive kindness. Offer support with words like, “If you want to share, I am here to listen whenever and however you need me.”

Join us on Thursday, September 8, at 7 PM ET/4 PM ET, as Executive Editor Lisa Hostein moderates a discussion on moving from profound sorrow to meaningful healing in advance of the new Jewish year. Panelists will include author Kathryn Schulz (Lost & Found), Rebecca Soffer (The Modern Loss Handbook) and Hope Edelman (The AfterGrief). Free and open to all. Register here.

In The Modern Loss Handbook, Soffer suggests that simply grounding your remarks in the moment can be comforting: “How are you today? What’s going on for you now?”

When Schulz was mourning her father, she found it helpful to push herself to be out with people, when her instinct was to crawl into bed.

On the other hand, Rubel, then a 48-year-old widow with three children, found solace in isolation. “I had never been alone,” she said. “At 19, I’d gone directly from my parent’s home to my marriage. I felt smothered by everyone wanting to help me. I missed being loved and loving. I realized I needed to find out who I was without my adoring husband and what I could do by myself, without him or my children.”

Against everyone’s advice, for three months she relocated to a small vacation apartment the couple owned in Aspen, Colo. “It was hell at first. I was horribly lonely,” she recalled. “But slowly, a good therapist, a lot of journaling and the beauty of the mountains helped me separate myself from Rick and his death and learn that I could be alone without being lonely.”

In dealing with grief, a piece of advice I have heard is to remember the wonderful person you lost rather than remembering that you lost a wonderful person. One palliative way to deal with memories is to make what Soffer calls in The Modern Loss Handbook “a memory box.”

In the painful process of culling and disposing of your loved one’s possessions, keep some things that will trigger good memories: a hand-written note, pages torn from their favorite book, a scarf or a bracelet, ticket stubs for an event you attended together. I still have a little spiral notebook where my father kept a log of his Coast Guard watches during World War II. Seeing his handwriting always makes me smile.

A recurring theme among the authors I spoke with was storytelling as a balm for easing the emptiness of mourning. “We grieve through telling our story and sharing it,” said Edelman.

Initially, your story will be about the how, when and where of what happened. Over time, it will expand to how your life was affected by your loss. Storytelling builds bridges with other mourners, explained all three of the writers I spoke with. It attracts the support team that will assist your journey and opens new pathways to healing. Talking about your grief helps make sense of it. It leads to the day when you wake up and are surprised to notice that the world is no longer draped in gray.

I still remember the day, eight bleak and dreary months after my father died, when I noticed the tulips were in bloom. I’d begun to heal.

A piece of advice I often heard after my sister passed away is to find a grief counselor who will listen and not judge your progress. Should your malaise and lethargy sink into ongoing depression, that’s the sign that a therapist is not merely suggested but strongly advised. Another valuable tool is finding an anchor outside yourself to pull you from despair.

Schulz believes that healing won’t come until you manage to get out of yourself and attach to something else—friends, literature, yoga, nature, whatever—and focus on what you have, not what you’ve lost.

“Life is full of surprises,” Schulz said, “and we must never give up on the possibilities of discovering joy and gratitude, love and generosity, in the world.”

A grandmother who’d lost a grandson to leukemia told me that not until she realized that she needed to be present for her remaining grandchildren was she finally able to start putting one foot in front of the other and begin her journey.

While the intensity of grief diminishes with time—that most dependable of healers—it never completely disappears. It morphs into long-term bereavement, or in Edelman’s lexicon, AfterGrief, which she imagines as a black spot of misery in the middle of a white circle representing life. The spot doesn’t fade or shrink, as is commonly believed. But as the months and years pass, the white circle of life expands, making grief much smaller and less influential by comparison.

Still, there will always be moments when the stab of heartache surfaces.

“Deathaversaries” is what Soffer calls the holidays, birthdays and anniversaries that trigger a bout of grieving. Milestones you had expected to share—a wedding, a bris, a graduation—can be especially hard. Even a favorite song on the radio can evoke a pang of sorrow.

When my book Sisters hit The New York Times best-seller list, my joy was briefly pierced by the sorrow that my father wasn’t alive to celebrate with me. But I have to welcome those reminders, because I never want to lose my attachment to those I’ve lost or the memories they’ve left behind.

I have settled into the desired destination of all who grieve. It’s a place Edelman described, where grief has become a ghostly traveling companion, but no longer an unbearable burden. I can be sad, but I am healed.

Carol Saline is a journalist, speaker and author of the photo-essay books Sisters and Mothers & Daughters.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply