Arts

Zionist Home Goods

A brass plate depicting the biblical figures of Jacob and Rachel surrounded by grapevines. A cigarette box with a green patina, its clasp decorated with a miniature relief of the Land of Israel. A sleek silver Shabbat candelabra inspired by the German Bauhaus movement.

While the plate and box are household items and the candelabra is a piece of Judaica, all three are examples of Israeliana—decorative and ritual objects made in Israel, largely in the early through mid-20th century.

A look around your home, and those of your parents or grandparents, will likely yield examples such as a bronze menorah with a relief of the 12 Tribes of Israel; plates decorated with agricultural motifs; or small bowls with a green patina—all picked up as souvenirs on a trip to Israel or bought at a Zionist fundraising fair in America. Once dismissed as tchotchkes, these objects are now valuable both historically and, for rare finds, monetarily. And while some experts only consider metalware to be Israeliana, collectors have expanded the category to include ceramics and glass items as well as ephemera such as posters and postcards.

Interest in Israeliana is growing at auctions, and museums are recognizing its importance as well. For the first time, the Israel Museum in Jerusalem has on display, through early May, items from its collection of Israeliana, including the Bauhaus-inspired candelabra and the Jacob and Rachel plate.

“We judge these items based more on their historical rather than artistic value, but with the perspective of time they have become increasingly appreciated,” said Sharon Weiser-Ferguson, senior curator for the museum’s Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mandel Wing for Jewish Art and Life.

Their allure is attributed to several factors, including nostalgia for a simpler time and Israeliana’s connection to the history of Israel. Many of the pieces are tied to the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts (now the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design), founded in Jerusalem in 1906 by the Lithuanian-born artist Boris Schatz.

To support itself in its early days, Bezalel established workshops producing practical and decorative objects that could be sold locally as well as abroad. As a result, early examples of Israeliana mirror the detailed patterning and ornamentation of the late-19th century European Arts and Crafts movement favored by Schatz.

Although the designs show European influences, the methods and materials used in the early pieces reflect the difficult economic situation in the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine before statehood. Unlike in Europe, where Jews commissioned sterling silver pieces for their homes, the best material that Bezalel artisans then had to work with was silver plate. For the most part, artists and craftspeople used bronze and brass, which were far cheaper and more accessible. Even British shell cases from World War I were re-purposed into art.

Toronto attorney David Matlow owns a shell case engraved with the likeness of Zionist pioneer Theodor Herzl and marked as having been produced at a Bezalel workshop, probably in the early 1920s.

“There are about 50 pieces of metalwork Israeliana—including some made by Boris Schatz himself—among the more than 5,000 items I have that relate to Herzl,” said Matlow, owner of what is likely the largest privately held collection of Herzl memorabilia, which he has displayed at synagogues and other Jewish venues in Canada.

One of Matlow’s favorite metalware treasures, despite having no connection to Herzl, is a menorah with a green patina that is adorned with an oil jug and laurel branch.

Indeed, Israeliana Judaica as well as household items such as plates and ashtrays often feature archeological references like ancient coins and oil lamps. “This was a way to show that Jews were not new to the land,” Weiser-Ferguson explained. “We also see military references, biblical characters, the Seven Species, the 12 Tribes, figures working the land as well as Zionist leaders.”

Bezalel closed in 1929 amid financial difficulties, then reopened in 1935, attracting refugees from Nazi Germany who had studied in the Bauhaus school. The new immigrants’ Modernist and International school training is reflected in the minimalist aesthetic of some of the Israeliana produced in that period.

Exploring Israeliana: A Virtual Event

Join us on May 12 at 12:30 p.m. as Hadassah Magazine Executive Editor Lisa Hostein hosts curators from the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, including senior curator Sharon Weiser-Ferguson, for a discussion about “Israeliana”—Israeli tchotchkes especially popular with tourists beginning in the early years of the state. Free and open to all. Register here for the event.

Dr. Ella Tenenbaum-Koren, whose parents, Zvi and Rivka Tenenbaum, donated some 60 pieces of Israeliana to the Israel Museum in memory of their son, Yadin, who was killed in the Yom Kippur War, is partial to the style introduced by the German Jewish refugees. “My preferred items are modern and minimalist—both the everyday items and the Judaica,” said Dr. Tenenbaum-Koren, a former medical director for Pfizer Israel who lives near Tel Aviv.

The family has also donated or lent pieces from their extensive collection to other museums in Israel, Europe and the United States. In recent years, Dr. Tenenbaum-Koren has taken on the role of guardian and grower of the collection.

Among her favorite designers is Dov Bernhard Friedlander, who immigrated to then-Palestine in 1934 and opened his own workshop where he created silver and silver-plated items—the material reflecting something of an economic upturn for the Jews in the region. Included in the family collection are that sleek silver two-branched candelabra meant for Shabbat use and geometric silver teacup holders typical of the Bauhaus style.

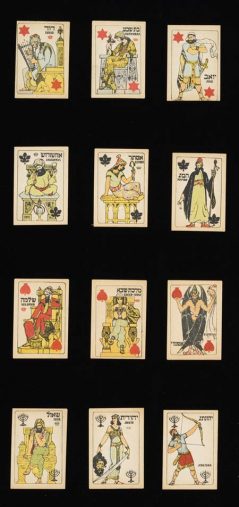

Designers from both the earlier and later periods often trained and then worked at Bezalel. Others opened their own workshops or designed for larger companies. Ze’ev Raban, for example, who came to Ottoman Palestine in 1912, created pieces for a variety of manufacturers. Raban is perhaps best known for merging biblical imagery with art deco and Orientalist motifs for travel posters and even commercial packaging. A deck of his playing cards, decorated with images of biblical figures like King David and Bathsheba and with the suits reconfigured as Stars of David, menorahs, fig leaves and pomegranates, is in the collection of The Jewish Museum in Manhattan.

However, among American tourists, perhaps the best-known Israeliana company was Pal-Bell, co-founded by artist Maurice Ascalon in 1939. Ascalon invented the unique green patina that became a hallmark of Israeli craft items. Pal-Bell and other manufacturers used the patina to “age” objects, causing them to resemble ancient artifacts dug up in the Holy Land. It was also in the late 1930s that producers of Israeliana turned to metal casting, i.e., a way to mass produce items by pouring molten metal into a mold.

For the most part, producers of Israeliana saw themselves as designers and artisans, and not as artists.

“The difference has to do with the change in perspective we have on what they created. It used to be that they produced objects and saw themselves as craftsmen,” said Weiser-Ferguson. “Today, we regard them as artists.”

The artwork they created is both affordable and accessible to collectors. According to Dr. Tenenbaum-Koren and Matlow, it is not difficult to break into collecting using online resources and second-hand shops in the United States and Israel.

And with Israeliana’s popularity beginning to trend upward, now may be a good time to start. Handmade items from the earlier period will be more expensive than mass-produced objects, with prices ranging in the tens to hundreds of dollars.

However, Dr. Tenenbaum-Koren emphasized that, at least for her, it’s not about the monetary value.

“I love Israeliana because of the memories and nostalgic feelings it evokes,” she said. “It reminds me of Israel’s past.”

FINDING ISRAELIANA

Etsy and eBay are good places to start. Search the sites for “Israeliana” or the names of designers and manufacturers.

Auction houses such as Kedem and Kestenbaum & Company frequently feature items created pre-statehood and during the early decades of the Jewish state.

Renee Ghert-Zand is a Jerusalem-based freelance writer and journalist covering Israel and the Jewish world.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply