Arts

Boxer Harry Haft Is ‘The Survivor’

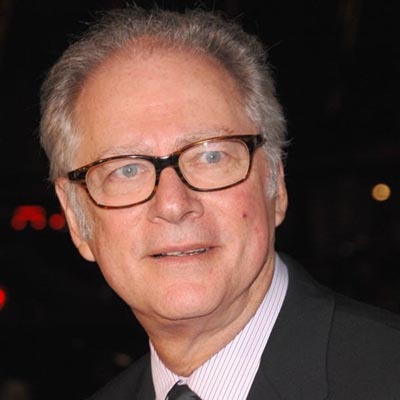

Barry Levinson may have been a Hebrew school dropout, as the famed director has mentioned in interviews about his Jewish background, but he didn’t leave his Yiddishkeit behind. That is obvious in his latest film, The Survivor, based on the real-life story of boxer Harry (Herschel) Haft, which will premiere on HBO Max on April 27 for Yom Hashoah, which begins that evening.

Haft was a Polish survivor of multiple concentration camps, including Auschwitz, and Ben Foster plays him with verisimilitude and a multilayered poignancy.

About half the film is set in the camps, where Harry, at age 16, is trained to box by an SS officer and forced to compete in a series of brutal matches with fellow prisoners for the amusement of the Nazi guards. The losers are shot. Harry eventually escapes the Nazis in April 1945 during a death march, but not the experience.

After the war, Harry comes to the United States and settles in the Brighton Beach section of Brooklyn, where he becomes a prizefighter. The film depicts his suffering from what today would likely be called post-traumatic stress disorder. Plagued by anger and guilt, he lashes out at everyone, including his wife, Miriam (Vickie Krieps), and their children. He also remains resolutely silent about his concentration camp experiences—a familiar theme for those who know survivors.

But what most fascinated me in Levinson’s film is an emotion rarely conveyed in discussions about survivors: the desperate hope they carry that somehow loved ones whom they lost touch with survived. Harry longs to be reunited with his childhood sweetheart, Leah, whom he last saw carted away to the camps. It’s why he continues to box, pressing for a match with popular boxer Rocky Marciano, a future heavyweight champion, convinced that press coverage of the event would let Leah know he is still around. When Harry and other survivors gather at the film’s end to sing “Gott Bentsch Amerika” (Yiddish for “God Bless America”), there likely won’t be a dry eye in your house.

Levinson is best known for award-winning films such as Rain Man, Good Morning, Vietnam and Bugsy as well as his television work on shows including Homicide: Life on the Streets. But in certain circles, his fame comes from his films based on his personal life and background as the descendant of Jewish immigrants.

Among these films is Avalon, inspired by the story of his maternal grandparents, Sam and Eva Krichinsky. They arrived in Baltimore on a July 4 convinced that the fireworks they witnessed were America’s welcome to them. Then there is the coming-of-age film Liberty Heights, in which Levinson recalls his efforts to crash a public pool that barred Blacks and Jews.

In The Survivor, too, the director’s memories influence his work. Levinson grew up in Baltimore sharing a house with his extended family. When he was about 5, “this man shows up at the door, and we found out it was my grandmother’s brother,” he said in an interview with Hadassah Magazine. His grandmother had never mentioned that she had a brother named Simcha.

“He stayed with us for two weeks,” Levinson recalled. “They put him on a roll-out cot in my bedroom. On the first night, he started thrashing around in the bed and then, all of a sudden, he’d quiet down. That went on night after night, and I just figured he was having nightmares.

“Then jump ahead to where I’m maybe 16 years old. I’m sitting with my mother in the kitchen and something [prompted her to say], ‘You know Simcha was in the concentration camp.’ That was the first time I heard that…. And we never talked about it again.”

The silence around the Holocaust and the suffering of survivors stayed with him. Like his great uncle, said Levinson, Haft was “haunted.” The question The Survivor asks, the director said, is, “Now that it’s over, how do you go on with your life when the demons keep hanging around in your head?”

Curt Schleier, a freelance writer, teaches business writing to corporate executives.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply