Israeli Scene

Feature

In Israel, Breaking Barriers in the Orthodox World

In October 2020, when the Torah reader at Shirat HaTamar, a Modern Orthodox congregation in Efrat, realized—mid-sentence—that an ever-so-slightly scrunched letter might render the Torah unkosher, the shul’s leaders called on their resident expert in Jewish law: Shira Marili Mirvis.

Mirvis, who was then in the final year of a five-year program in women’s halachic leadership, walked from the women’s section to the bimah and carefully examined the Torah. After informing the congregation that the Torah was indeed kosher, the Shabbat reading continued.

“After I sat back in my seat in the women’s section, behind the mechitzah, I realized I was asked, and I answered, a halachic question for the whole synagogue that a synagogue’s rabbi would ordinarily answer,” Mirvis said.

Less than a year later, in May 2021, Mirvis officially began to lead Shirat HaTamar, a vibrant 42-family synagogue that was established three years ago in her West Bank settlement near Jerusalem. She is believed to be the only woman in Israel to head an Orthodox synagogue on her own.

Mirvis, 42, who calls herself a rabbanit rather than a rabbi or rabba, has most of the responsibilities of a male Orthodox congregational rabbi, including answering questions on halacha (Jewish law), teaching Torah subjects to adults and youth, reading the haftarah on Shabbat and delivering sermons. But unlike a male rabbi, she is not counted in a minyan, so she cannot lead prayers or officiate at weddings. Male congregants lead the davening and read from the Torah—just as they did before Mirvis headed the synagogue.

The synagogue’s decision to hire Mirvis was “a natural progression,” said Rami Schwartz, a Shirat HaTamar board member. “She and her family have been members of the community since day one. She shared Torah, taught classes, and people started coming to her with halachic questions. People gravitated to her and saw her as a de facto leader of the kehillah, our synagogue community.”

The bottom line, Schwartz said, is that “when people in a community have a question, they go to their community rabbi. It’s natural that we go to Shira, we trust her knowledge and humility. When she herself needs to go to her teachers for guidance, she does. That’s an important quality in a leader.”

For an Israeli Orthodox synagogue to appoint a woman as the sole religious leader “is pathbreaking,” said Adam Ferziger, a professor at Bar-Ilan University’s department of Jewish history and contemporary Jewry. This is especially true as “it implies that she is a halachic authority, which is an area, a role that even many moderate Orthodox figures would be reticent offering to a woman.”

Ferziger estimated that about five or six other Modern Orthodox synagogues in Israel have women who serve as assistant rabbis or in partnership roles with male rabbis. “It’s a slow, incremental revolution, but it’s still avante-garde,” he said.

Mirvis earned a heter hora’a—a permit to teach Jewish law, commonly known as a certificate of semicha—by passing the same exam that male rabbinical students in Israel must take before the Chief Rabbinate certifies them as rabbis. The Rabbinate, a strictly Orthodox and state-funded institution that has a monopoly over virtually all matters related to official Jewish life in Israel, does not permit women to take their semicha test.

In July 2021, Mirvis received her heter hora’a from the Susi Bradfield Women’s Institute of Halakhic Leadership, a part of the Ohr Torah Stone educational network. She was handpicked to lead Shirat HaTamar by Rabbi Shlomo Riskin, the founding chief rabbi of Efrat and founder and chancellor of Ohr Torah Stone.

READ MORE: Transforming the Rabbinate Over 50 Years

“This has always been a dream of mine, to see a woman like Shira being a leader of a Jewish community,” Riskin, 81, told Hadassah Magazine. “The first rebbe who taught me Gemara was my maternal grandmother, who learned from her father, a rabbinic court judge in Europe.”

Mirvis was born in Jerusalem into an Orthodox Sephardi family that considered their local synagogue, which was headed by Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu before he became a chief rabbi of Israel, their second home.

She insists that her desire to lead a synagogue and be a poseket halacha—a rabbi-scholar who rules on halacha—is motivated by her desire to serve her community, not to rock the boat of Orthodox Jewish practice.

“I grew up in a family obligated to halacha and, at some point, I realized I hadn’t learned how rabbinic decisions were made, and I wanted to know. At a time when Jews can simply Google a question, a posek gives an answer that is tailored to the specific question and situation.”

She sees herself as a pioneer, yet firmly within the boundaries of Jewish law. “I’m not trying to break tradition,” Mirvis emphasized during an interview in her book-lined, toy-filled home in Efrat. “I value tradition very much.” At the same time, she wants to be the “halachic woman figure” whom Jewish women—and men—can go to on a variety of issues.

She said she wishes that such a woman had existed when she got married 18 years ago and a year later, when she experienced a miscarriage. “I had a lot of halachic questions and I wanted to learn what was minhag—tradition—and what was halacha, but I felt embarrassed asking a man.”

While several women had by then graduated from the yoetzet halacha program of the Nishmat Center for Advanced Torah Study, where they became experts in the area of taharat hamishpacha, Jewish law that relates to marriage, sexuality and women’s health, “they weren’t accessible to me,” Mirvis said. “Unlike today, there was no yoetzet halacha hotline.” Nor were they trained to answer Mirvis’s many questions unrelated to those issues, she said.

Mirvis’s husband, Shlomo, the founder and CEO of a tech startup company, calls himself “rebbetzman.” They have five children, ages 7 to 16.

By the time Mirvis’s father died four years ago, and an ultra-Orthodox member of a Jerusalem chevra kadisha forbade her from making a tear in her clothing as a sign of mourning at the cemetery because it would be “religiously immodest,” she knew enough about Jewish mourning practices to insist on tearing her garment. “I told him, no, I need to do this now, and I ripped my shirt,” she recalled. “Of course, I was wearing a shirt underneath.”

From its inception, Shirat HaTamar—which gathers in a kindergarten on Shabbat and holidays but has been allotted land to build a permanent structure by the Efrat municipality—follows the religious guidelines set forth by Riskin, including what women can and cannot do from a religious perspective.

“I’m not counted in the minyan, I’m not the chazanit [cantor], I don’t wear a tallit or tefillin or read from the Torah,” Mirvis said. “We do everything within the boundaries of halacha, so there are so many things that I can do.”

Mirvis said she sometimes feels saddened by the fact that women are not counted in a minyan. “It does bother me, but I bend my wishes to halacha.”

More than anything, she said, “the essence of my role is to be available to people, to answer their questions. I see myself in charge of enhancing options to whoever wants to learn Torah and halacha.”

In addition to offering classes on different aspects of Jewish law and answering members’ questions—everything from building a kosher-for-Sukkot pergola to surrogate motherhood—Mirvis ushers her congregants through Jewish calendar and life-cycle events. She works to help prepare every prospective bar and bat mitzvah child in the synagogue, and offers halachic guidance and emotional support to members navigating the loss of a loved one.

WATCH NOW: CELEBRATING 50 YEARS OF FEMALE RABBIS

A virtual event featuring Rabbis Sally Priesand, Sandy Eisenberg Sasso, Amy Eilberg and Sara Hurwitz, all of whom made history by becoming the first ordained rabbis in their respective denominations.

Asked whether being a rabbanit and not a male rabbi brings “added value” to her synagogue job, Mirvis grew pensive. “I don’t know how to answer,” she said. “I think the role is similar, in that I make halacha accessible to the community.”

But, she asked, “In what way am I different? On Rosh Hashanah, I gave my dvar Torah outside due to corona, in the parking lot, to more than 100 people. I started crying, and my community starting crying. At the end of the prayers a male rabbi came up to me and said that this is the power of a woman rabbi. She will allow herself to cry in front of her synagogue. I feel comfortable crying in front of them, but I grew up in a small family shul and the male rabbi cried all the time.”

Mirvis’s congregants say she brings a perspective and experience not shared by male rabbis. “As a religious woman I always had to go to male rabbis, even when I didn’t want to, so sometimes I didn’t go,” said Renana Stern, a member of Shirat HaTamar.

Stern said that Mirvis “looks at issues from her perspective as a woman, a wife, a friend, a mother as well as an expert in halacha. Her leadership and her ability to be in touch with her emotions makes everyone feel secure to speak with her.”

Mirvis’s role extends beyond the synagogue. In Efrat, which has only two paid kashrut supervisors—both male—she has been entrusted by the municipality’s religious council with checking the kosher standards of at-home food businesses run by women. For the moment, she does so on a voluntary basis, she said, because there is no budget for a third supervisor.

The same is true of her volunteer work, which she sees as an extension of her role as a rabbanit. She guides mikveh attendants at the local mikveh, comforts families in the Covid ward of Shaare Zedek Medical Center and works with the local burial society. She also teaches, for pay, at various educational institutions.

Despite her considerable involvement in the community, some rabbis in Efrat refuse to recognize Mirvis’s authority and have distanced themselves from her. Soon after the news broke that Chaim Walder, a well-known children’s author, rabbi and therapist in the ultra-Orthodox community, was accused of serial sexual assault, including of children, several Efrat rabbis signed a letter recognizing their community’s obligation to deal with sexual abuse. After Mirvis signed the letter, a few of the signatories removed their names.

“It was very sad,” she said. “It was more important to them to not have their names next to a woman’s than to tell their communities they’re here for them.”

Riskin said that graduates of the Bradfield institute and other Orthodox women’s centers of learning are being accepted for a wide range of positions that were traditionally held by Orthodox men. But Riskin, the founding rabbi of Lincoln Square Synagogue in Manhattan before making aliyah in 1983, acknowledged that there are still many Orthodox rabbis and institutions that reject the notion that women can be halachic authorities, especially in synagogues, because they don’t want to be accused of changing the religious status quo.

Many in the Orthodox world worry that “it would appear that they are accepting Reform or Conservative practice,” Riskin said. “They’re afraid of the slippery slope.”

Rabbi Kenneth Brander, president and rosh yeshiva of the international Ohr Torah Stone network, agrees. While he is immensely proud of Bradfield institute graduates, he said, calling them rabbis “can put at risk the work that we do. It scares parts of the Orthodox community, because they are sensitive to the nuances and terminologies of halacha.”

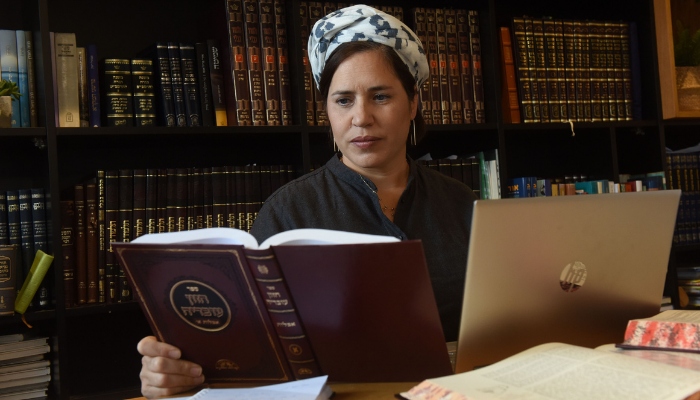

Meanwhile, Mirvis, seated at her dining room table, her computer open while thumbing through Jewish texts—a Gemara, Shulchan Aruch and Hazon Ovadia—welcomed her children as they arrived home from school. She then cited a midrash.

“It is said that every soul of Am Yisrael, the Jewish people, has a letter in the Torah. I identify with this,” she said. “The Torah belongs to everyone.”

READ MORE: Envisioning the Rabbinate Through a Different Lens

Michele Chabin is an award-winning journalist who reports from Israel.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Shoshana says

While I enjoy reading Hadassah Magazine, I find there are very few featured stories about Orthodox women and the Orthodox–not traditional and not leftist–perspective. Thank you for FINALLY including a feature story about an Orthodox woman in your publication! We count, too! Our diversity as Jews includes frum/Orthodox persons and balanced reporting includes Orthodox women making a difference! Please include more stories about Orthodox women!

Vicky P. says

“She was handpicked to lead Shirat HaTamar by Rabbi Shlomo Riskin, the founding chief rabbi of Efrat and founder and chancellor of Ohr Torah Stone.”

Shame! Letting a man pick her as if she is some object to throw around and place in a synagogue.