Being Jewish

Commentary

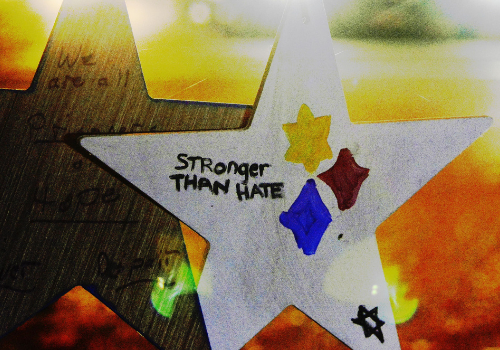

Banding Together to Fight Antisemitism

“Epes tut zikh.” This Yiddish phrase, which I learned from my mother-in-law, means “something is happening.” As she explained to me recently when we were stuck in traffic for no reason that we could discern, it must be “epes tut zikh.” She gave me another example: When my late father-in-law was a medical resident and stood outside a patient’s room with his fellow young doctors, the chief resident would say, “We have a grand case of epes tut zikh here. Can someone explain?”

Something is happening today regarding the spike in antisemitic acts in the United States, and there are no discernible reasons to explain why. The questions are: What exactly is happening and what can we do about it? To address the first question, the vigilant among us can consult the Anti-Defamation League’s Tracker of Antisemitic Incidents, which provides up-to-the-minute data points of where, when and to whom “something is happening.” The second question is more difficult to answer.

It is hard not to feel afraid when we never know where and when danger will strike, whether from a mysterious virus with the capacity to disable our lungs or from another human who wants to do us harm only because of our faith.

The Talmud deals with this very issue—that there are places of danger—and accordingly teaches that daily prayers should be abbreviated in such circumstances. A Jew who is walking in a place of danger should recite a brief prayer that keeps the focus on the community by using “us” instead of “me” (Berachot 29b). Why should community be paramount in a moment of potential personal danger? Further down on that same page in Berachot, we learn the answer: “At all times, a person should associate himself with the congregation [not pray for himself alone]. How should he say it? May it be Your will, Lord our God, that You lead us to peace.”

The solution of the Talmud, adjusting our behavior to be as proactive against danger as possible while fostering togetherness, seems like the correct one. There are many ways to express Jewish peoplehood if you are not a shul goer: take a Hebrew class, see an Israeli movie, have a Shabbat or holiday meal with other Jews, laugh at Jewish jokes. What is essential is gathering as a community.

These remedies don’t remove our basic sense of fear at present; there are many reasons to be afraid. So where to find hope? One place is with our Jewish calendar, whose circularity is epitomized in the biblical expression “teshuvat hashanah,” the turning of the year, or for those who know Hebrew, the repentance of the year.

Despite multiple reasons for gloom, the Days of Awe, the High Holidays, bring us renewal. The Psalm traditionally read during Elul, the month preceding Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, instructs Jews to “let your heart be strong and of good courage and hope in the Lord” (Psalm 27:14). Strengthening ourselves can come in many forms, both physical and mental. As Jews there are many ways to connect to tradition: through learning Jewish languages like Ladino, Yiddish or Hebrew; performing Israeli dances; studying Jewish texts or joining a Jewish book group; and praying with a synagogue community. Countering hate against Jews requires defying the goal of the attacker—to destroy Jewish lives and values.

I have been thinking about these matters for the past three years. On the 18th of Heshvan, corresponding to October 24 this year, we will commemorate the third yahrzeit of the 11 Jews who were killed in their synagogue on a Shabbat morning. There were three congregations—including New Light Congregation, where my husband, Jonathan Perlman, serves as rabbi—that shared space at Tree of Life in Pittsburgh. Nine families are bereft of spouses and parents, children and cousins, grandparents and aunts and uncles.

As my family and others in Squirrel Hill anticipate the upcoming anniversary, I would prefer to spend as little time as possible thinking about that awful day. But the steep rise in the number of antisemitic attacks since then, and the effort of trying to battle it, force me to recall my own difficult experiences.

One of the many things that helped me cope with the tragedy was studying and writing about the weekly Torah portion. Another was teaching congregants how to chant haftarah, both to increase their knowledge and connections to synagogue life and to honor the three from the New Light Congregation who were killed that day, who were all regular haftarah chanters.

Yet another way to counter antisemitism is to let antisemites know we are present. When my father-in-law was in medical school in the late 1950’s and Jewish quotas were still in effect at many institutions of higher learning in the United States, one of his Jewish classmates would tell him which professors and students were antisemitic and the offensive things they said. My father-in-law, Larry Perlman from Brooklyn, never hid his identity, but the classmate was from a family who had changed their name from the original Goldberg to something neutral. My father-in-law’s advice to his friend?

“Change your name back to Goldberg and you’ll never hear that stuff again,” he said, thinking the speakers would be too embarrassed to spout such hate to the face of a person who is clearly a Jew.

Today, the answer is not so simple. In many cities in America, Jews who look obviously Jewish have become targets for violence. Still, the spirit of the sentiment is right. Let us be strong and strengthen ourselves in our understanding and practice of Judaism in whatever ways are important to us. And be of good courage; don’t be afraid to let those around us know our identities, while still diligently maintaining our personal safety.

And finally, we all need to take heed of the “somethings” that are happening around us, adjust our behavior and band together.

Beth Kissileff is co-editor of Bound in the Bond of Life: Pittsburgh Writers Reflect on the Tree of Life Tragedy and author of the novel Questioning Return.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply