Hadassah

Feature

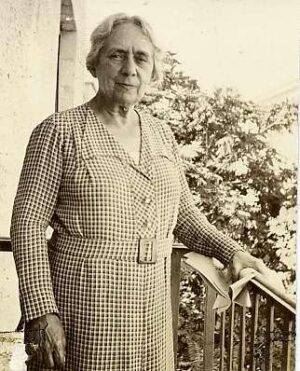

The Two Lives of Henrietta Szold

Henrietta Szold was one of the most important Jewish leaders in the 20th century. Her long life, from 1860 to 1945, spanned some of the most turbulent years in modern history, when great waves of immigration transformed the United States into a powerful nation and social revolutions and two global conflicts played out on the world stage. These events, which shook and shaped the lives of millions of people, are woven into the fabric of her own life story.

Henrietta’s life was divided into two distinct parts, before she founded Hadassah and after, so different from each other as to appear to belong to two separate people. What remained consistent, however, was her lifelong commitment to tikkun olam, repairing the world. As a young woman, she encountered many immigrants in the streets of Baltimore searching for work to support their families. In 1888, Henrietta decided to establish an English-language night school in order to help them become integrated into the economic and cultural life of America. Though she had little financial resources of her own, she devoted all her energy to the organizing, fundraising and pedagogy required to make the school a success. Thousands of immigrants studied in the school, which was open to everyone, regardless of religion, gender or age. Her enterprise soon became a model for similar schools across the country.

These same humanist and egalitarian values, which became a signature part of her leadership style, provided the impetus to establish Hadassah. She was driven by a sense of mission, fighting against the exclusion and discrimination that she had experienced and witnessed during the first half of her life, all of which is reflected in the following excerpts adapted from my newly published biography, To Repair a Broken World: The Life of Henrietta Szold, Founder of Hadassah.

The life story of Henrietta Szold is filled with contrasts and tensions that had a profound influence on her public activities. She encountered situations in which women were excluded time after time in the workplace. But during the first half of her adult life, Henrietta passively accepted this discrimination without objection or protest. At the Jewish Publication Society (JPS), where she worked from 1893 to 1915, she edited and translated numerous works by some of the world’s greatest Jewish scholars. Her work was widely appreciated and admired, yet she was very rarely credited in the published volumes. Her formal title was “secretary” when in fact her job was that of editor-in-chief. Similarly, despite editing the American Jewish Year Book for 10 years beginning in 1898, and contributing dozens of articles to it, her name was hardly mentioned, nor did she receive any additional payment for her work on the annual publication. Henrietta loved her work on the Year Book [which was a JPS publication at that time] and considered it extremely important at a time when the only way to reach large numbers of people was through the printed word.

The Year Book allowed her to convey her messages to a sizable readership, especially her concerns regarding the alarming ferocity of antisemitism in Europe, which had also spread to American shores. Henrietta believed that antisemitism posed a grave threat to the Jewish people. She could not have been more prescient. Henrietta fought for the eradication of antisemitism and praised writers and thinkers of all faiths who raised their voices against it. She highlighted the achievements of Jews and their many contributions to society. And she drew attention to the accomplishments of Jewish women in the fields of literature and science in the United States and in Europe.

While determined and resolute in her literary work, even standing up to the directors of the publishing house when necessary, Henrietta was surprisingly passive when it came to standing up for her own rights in matters such as fair pay and due credit. This pattern of exclusion and discrimination repeated itself in her early efforts on behalf of the Zionist movement, for which she received no recognition, despite her important contributions.

Oddly, she never refused an assignment. Was it her way of coping with the need to operate as the only woman in a male-dominated environment? Even when she moved to New York in 1903 after her father’s death and sought admission to the Jewish Theological Seminary, she agreed to declare that she had no intention of serving as a rabbi. While at the seminary, she continued her work at JPS and began to translate and edit Louis Ginzberg’s Legends of the Jews. During the course of their work together, Henrietta fell in love with him. When her love was not requited, she sank into a deep depression. To aid her recovery, she embarked on a trip to Europe and Palestine in 1909, at a time when Palestine was still under Ottoman rule. Henrietta, though an ardent Zionist from an early age, found the “land of dreams” she had hoped to see a far cry from the reality she encountered there. She was shocked to discover that most of the Jewish inhabitants of the land lived in abject poverty, plagued by endemic disease and a high rate of mortality.

She understood that the Yishuv—the Jewish community of Palestine—could not develop and thrive under such conditions. Friends had warned her, before her trip, that visiting Palestine would cure her of her Zionism. On her return voyage she wrote, “The prophecy has not been verified. I am the same Zionist I was. In fact, I am more than ever convinced that our only salvation lies that way. The only thing I admit is that I now think Zionism an ideal more difficult of realization than ever I did before, both on account of the Jews themselves and on account of Oriental and world conditions.” The trip galvanized Henrietta’s desire to change the situation in Palestine even as it failed to alleviate the pain of her failed romance. Her depression worsened upon her return to New York, and she suffered a deep crisis that left her unable to function for months; it ended only when she concluded that her approach to life had been mistaken. She experienced an internal upheaval and made a dramatic decision to change her priorities.

Henrietta wrote to a friend in 1911 that henceforth she was determined to excise parts of her past life and open a new chapter. She began socializing again and enthusiastically joined public efforts to achieve women’s rights. This was a turning point. No longer would she allow others to infringe on her rights or take credit for her work. In 1912, she established Hadassah, a Zionist organization of American Jewish women, and was immediately elected president. It was the first time in her life that she received the recognition she deserved. Hadassah would become a crucial part of her struggle for women’s empowerment and equality.

The task that Henrietta envisioned for the women’s organization she sought to create was particularly complex, demanding simultaneous action on two geographically distant fronts, in America and in Palestine, with diverse needs, each requiring immense efforts. Henrietta had no illusions that any of this would be easy to accomplish, and therefore she wished to establish a large and powerful network, capable of contending with this twofold task. Henrietta knew that a large organization could not rest on the shoulders of a single individual or core group of members, as dedicated as they might be. She therefore sought partners to start chapters in cities throughout the United States.

She wrote to Julia Felsenthal, daughter of the late Bernhard Felsenthal, a Zionist Reform rabbi and friend of Benjamin Szold, Henrietta’s late father. Henrietta asked Julia to join Hadassah and open a chapter in Chicago. Julia accepted the challenge and went on to become one of Hadassah’s most enthusiastic members. Similarly, Henrietta wrote to friends in Philadelphia, Boston and Cleveland, describing Hadassah’s goals and asking them to establish chapters in their own cities. Thus began the first stage of Hadassah’s expansion to numerous cities and states throughout the United States. Henrietta then visited each of the new chapters, addressing members and encouraging them to recruit others. Henrietta was a well-known figure even before the founding of Hadassah, and many women came to hear her.

She spoke of the outhouses on balconies or in courtyards, each serving a number of families, filling the air with an overpowering stench. The hygienic conditions were extremely poor, with no sanitation services to speak of, increasing the risk of disease and contributing to a high mortality rate. When darkness fell, small kerosene lamps provided scant light, making the city look gloomy and hopeless.

Henrietta ascribed particular importance to the establishment of chapters in every city, but considered the existence of more than one chapter in a given city detrimental—a waste of energy and a source of potential rivalry. She did not want Hadassah chapters to become exclusive clubs, divided by socioeconomic class. She also strove to include both Eastern European women and women of Central European backgrounds. At the time, members of the well-established Jewish families, originally from Germany, tended to look down on the more recent immigrants from Eastern Europe. Henrietta saw the Hadassah chapters as places where members would focus exclusively on the goals of the organization, where each individual would contribute to the best of her ability.

Members were required to pay dues and were asked to solicit donations from friends and acquaintances. The membership continued to grow, as did the sums of money they managed to raise. More chapters were started, and within a few short years, there were Hadassah chapters throughout the United States, counting thousands of members. Henrietta managed the organization, her visits to the chapters and meetings with members alongside her work at JPS. The burden was great, but she never faltered in her efforts on behalf of Hadassah. Henrietta was receptive to ideas expressed by the members of Hadassah regarding the questions of the day, never giving orders or imposing her own views. At every gathering, she encouraged the participants to express their opinions, in order to underscore the fact that they were all equal partners. In the pleasant atmosphere that developed, the decisions that were taken engendered neither resistance nor resentment. She strove to make every chapter a cohesive group, acting in solidarity to achieve a common goal. Even decades later, this atmosphere persisted in Hadassah chapters throughout the country.

With the help of Hadassah, Henrietta established an infrastructure for medical health in Palestine with hospitals and clinics throughout the country. She also helped reform education and develop the social work profession in pre-state Israel. In one of her greatest achievements, she headed the Youth Aliyah enterprise in Jerusalem, saving thousands of orphaned children from the clutches of the Nazis both before and during World War II.

Henrietta became an admired leader in the United States, Palestine and many other countries. Her personal life, however, was not a source of comfort: Although surrounded by many friends, she suffered constant loneliness. On her deathbed, she remarked, “I lived a rich life, but not a happy life.”

This piece was adapted from To Repair a Broken World: The Life of Henrietta Szold, Founder of Hadassah by Dvora Hacohen, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2021 by Dvora Hacohen. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Hacohen, a professor of Modern Jewish History at Bar-Ilan University in Israel, has written several other books, including the prize-winning The Children of the Time: Youth Aliyah 1933-1948. She has received the Ben-Gurion Prize for her contributions to scholarship.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply