Family

Feature

My Cousin Fritz Was Married to a Nazi

My mother was a German Jewish refugee. In 1933, the year Hitler came to power, she sailed from Hamburg to New York, then headed west to San Francisco, where she met my father, Theodore Wolff, at a Jewish community center dance. When the war started, her family members in Europe were unable to escape. She lost nine relatives to the Holocaust, including her mother at Treblinka.

That family tragedy explains why, after my mother, Ruth Wolff, died in 2006, I was shocked to learn that for years, a Nazi had been a regular guest in our home. I discovered this when I tried to reach out to my father’s cousin Fritz in an effort to stay in touch with this beloved older family member.

Fritz Rinkel grew up in Berlin and, before the Nazis came to power, had wanted to be an opera singer. Sometime during the war, he escaped to Shanghai. In 1947, after learning that his parents had been killed in concentration camps, Fritz, then 32, sailed to San Francisco.

READ MORE: One Book, One Hadassah Pick: The Book of Lost Names

In America, he changed his name to Fred (though we would always call him Fritz), got a job as a singing waiter and later went on to co-own a tie store. He so loved to sing that he would break out in song anywhere, anytime. He often stood at the back of the Powell Street cable car on its last nightly run, belting out arias into the dark San Francisco streets. One late night, as the story goes, Fritz was singing on the sidewalk and a police officer nearly arrested him for disturbing the peace. But when Fritz began to sing Danny Boy, the Irish cop joined in and no arrest was made. I don’t doubt this story, for Fritz was amiable and good-hearted.

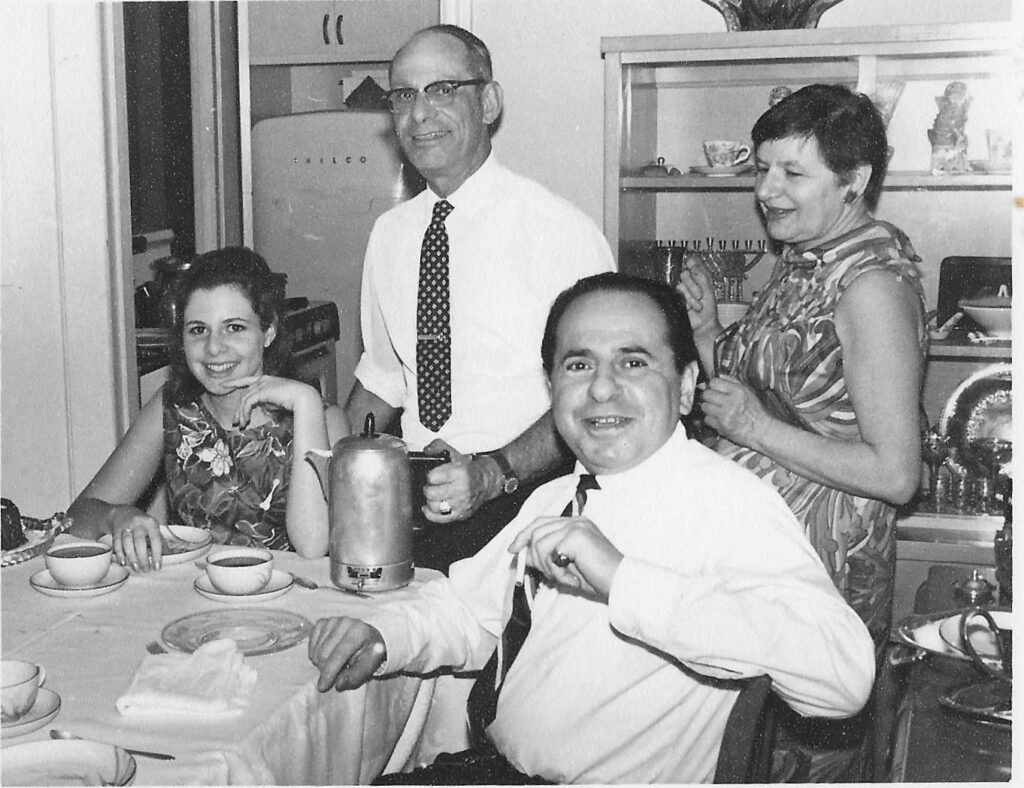

My family assumed that Fritz was a confirmed bachelor, but in 1962, at age 47, he brought over his fiancée for an introduction. He had met Elfriede Huth at a dance at the German-American club in San Francisco. Elfriede was not Jewish. That Fritz would marry a German non-Jew seemed odd to my parents, but this was America and the couple were in love. Even at the age of 14, I could see that Fritz was besotted with Elfriede, calling her “mein liebling,” my darling, throughout the evening and gazing at her with puppy eyes.

Photo Benjamin Sklar/AP Photo.

At the time, Elfriede was 39, plump, pretty and wore tight dresses. She had big blue eyes and pink cheeks. Her blond hair was braided and piled atop her head in the German style called Gretchen frisur. As boisterous as Fritz was, Elfriede was quiet. She spoke little, just giggled and blushed. She seemed to us—my parents, my older brother, Irvin, and me—sweet and very shy. When they left that first night, I remember my mother remarking, “Elfriede looks like a Käthe Kruse doll,” a well-known German doll with blue eyes and blond hair. And I remember, too, that she and my father were pleased that Fritz had finally found a wife.

For the next three decades, Fritz and Elfriede visited our home on occasion for family meals. My mother and Elfriede became cordial with one another, if not especially close. Elfriede worked as a furrier and helped my mother get a good deal on a coat with a mink collar. As the years passed, I saw Elfriede as no longer plump but heavy, and her shyness more like detachment.

Though Fritz and Elfriede had little money, they seemed happy and were always together. She went to synagogue with him, and each year they would walk arm-in-arm to the Hanukkah menorah lighting in San Francisco’s Union Square. They bought burial plots at the Jewish Eternal Home Cemetery in Colma, Calif., where they were to be buried together underneath a headstone that would feature a Star of David.

READ MORE: Female Courage During the Holocaust

My father died in 1991, and over the ensuing 10-plus years, my mother left San Francisco and, toward the end of her life, suffered from mild dementia. During those years, we lost touch with Fritz. After my mother died in 2006, I tried to call him to rekindle our relationship, but the number I had was out of service. So I did what most of us do when trying to track someone down. I Googled “Fred Rinkel” to investigate if Elfriede and he had moved.

In seconds, I was overwhelmed by the results of my search: sensational headlines from myriad international publications. “Her Secret Past as a Nazi Guard/S.F. Immigrant Married Holocaust Survivor, Attended Synagogue,” read one 2006 piece from The San Francisco Chronicle; “US Widow Deported Over Nazi Past” heralded the BBC in the same year. I learned two painful truths that day: That my beloved cousin had died in 2004, and that his cherished wife, Elfriede, had been a Nazi.

According to the numerous articles I read, Elfriede had served as a guard at Ravensbrück, the infamous German concentration camp for women where Nazis murdered 90,000, including children and babies. The camp’s 958 female guards were trained to speak filthy, degrading language to the female prisoners, threatening them verbally; deliver blows to their faces and bodies using fists or truncheons; kick them with their boots; and sic dogs on them. Ravensbrück was encircled by electrical wire, and those who tried to escape were severely beaten—sometimes to death.

I learned from multiple press reports that Elfriede had worked in that hellish place between June 1944 and April 1945. She had been taught to flog women with a whip and to use her SS-trained German shepherd to attack if she caught prisoners trying to escape. In the year she was there, 10,000 women were killed—by gas, beatings and malnutrition.

Photo courtesy of Maxine Rose Schur.

In my research, I found nothing remarkable in Elfriede’s childhood to explain why she chose to work at Ravensbrück. Elfriede, so simple and unexceptional, is just one more example of writer and political theorist Hannah Arendt’s term “banality of evil.” In Leipzig, she grew up in a lower-class family and was trained as a furrier. But furrier jobs were scarce during the war, so at age 21, she applied for a position at Ravensbrück after seeing an advertisement in the newspaper because, as she explained to one journalist, “It was easier than factory work.”

In 1959, she came to the United States sponsored by her brother, who had been a German POW in Wyoming during the war, but she never applied for citizenship, even after marrying Fritz. She had lied to the immigration officials on her entry documents, seeking to conceal her Nazi past. Indeed, according to Alison Dixon, Elfriede’s attorney in 2006, she revealed it to no one—not to her brother and not to her husband.

After Fritz died, Elfriede was seen by her neighbors as a poor, frail 84-year-old widow, according to most accounts. But one man apparently saw her as something else. Eli Rosenbaum was chief of the Office of Special Investigations, then a unit within the Criminal Division of the United States Department of Justice. Through years of meticulous matching of Nazi employment records with immigration rosters, in 2004, after her husband’s death earlier that year in January, Rosenbaum identified Elfriede as a guard at Ravensbrück.

On October 2, 2004, Rosenbaum climbed the stairs to Elfriede’s shabby top-floor apartment on Bush Street near the Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco. He confronted her about her Nazi past and the fact that she had lied about it to United States immigration officials. Elfriede claimed she was innocent. As she later attempted to explain her role at the concentration camp to The San Francisco Chronicle, “You have to watch so they don’t run away. That’s all. What’s going on inside, I know nothing about.”

But Rosenbaum didn’t buy her claims. As he shared during an NPR interview with Mike Pesca in 2006, “When you serve at a concentration camp, one’s job on a daily basis is to persecute human beings. That’s the entirety of the job.”

On August 31, 2006, the United States deported Elfriede to Germany, where she died in a nursing home in 2018. To the end, Elfriede was defiant and angry. She insisted in numerous media interviews that it was wrong to accuse her for something she did so long ago. “That is so far back,” she complained to The San Francisco Chronicle after she had been deported. “Everything is forgotten. Forget it. Forget about it!”

I have inherited the family photo albums. Now, as I pore over old snapshots, I cringe at some of the images of family gatherings. There is Elfriede helping my mom in the kitchen on Thanksgiving, the two women showing off the glistening turkey. There is Elfriede at another cousin’s home with two little girls smiling at her across the dinner table.

For so long, Elfriede, unlike other concentration camp guards, escaped justice. But truth is said to be the daughter of time, so it is this one deathless thing—truth—that Elfriede did not escape. Nor could she escape the collective memory of the horror she helped perpetrate. For despite Elfriede’s claim that “everything is forgotten,” I cannot forget her ruthless deception of our family, especially how she so callously duped our cousin Fritz. I cannot forget her lack of remorse for her cruelty. I cannot forget my mother’s lifelong grief at the loss of her family members murdered by the Nazis. The knowledge that she had hosted a Nazi in her home would have felt like a dagger in her heart.

Most of all, I cannot forget that Elfriede wanted us to forget.

That is why I am sharing my memory of her and Cousin Fritz, for it is not solely a grotesque story belonging to my family. As Elie Wiesel so powerfully wrote in Night, “To forget would be not only dangerous but offensive; to forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.”

Maxine Rose Schur is an award-winning children’s book author, travel essayist and writing instructor (maxineroseschur.com).

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Fran Bluestone says

What a remarkable story. May we never forget and we must teach our children and grandchildren so they never forget.

Deana says

Reading about this gave me goosebumps as to how many more ‘guards’ escaped to live out their lives as if what they did should ‘be forgotten’. We should never forget and never stop searching for those who went unpunished for their contributing to the brutalization of a group of people, just because they were different.

Harry Elliott Simon says

Thank G-D that we now have the strong State of Israel.

Sue H Normoyle says

My Cousin Fritz was married to a Nazi,is there a zoom for this??

Talia Liben Yarmush says

We don’t currently have any events scheduled around this essay.

Ben Hervey says

This reminds me of a verse from Torah my mother often quoted: “take note, you have sinned against the LORD; and be sure your sin will find you out” (Bamidbar 32:23).

Michael Heymann says

What a remarkable story. I would love to know who your Rinkel ancestors are. I have made a research on the Rinkels back to the beginning of 1700. They are a branch of my family. I managed to fit Fritz in,

Maxine Rose Schur says

Hello Michael,

I don’t not know who Fred Rinkel’s ancestors were. He was related to my father, Theodore Wolff but I do not really know the connection.

Apologies for the delayed response. I just saw your comment today.

Maxine