Health + Medicine

Feature

The Push for Genetic Literacy

Hadassah’s exome database is among the latest tools in analyzing genetic diseases

We know that almost everything is written in our genes, but we are still learning to read the writing. Most important is finding the typos—a misplaced letter or two among the three billion that comprise each individual’s blueprint—that predispose adults to cancer, Alzheimer’s or heart disease; make babies unable to swallow their milk; paralyze apparently normal toddlers; send infants into relentless seizures; and much, much more.

Hadassah Hospital Ein Kerem is among the global frontrunners in this urgent push toward genetic literacy. This past year, it has launched a powerful new homegrown tool—the creation of a virtual database called Hadassome, which catalogs genetic information of more than 6,000 people (and counting), along with the gene variants that cause disease.

Among these 6,000 is an 8-month-old Jewish baby girl who was recently brought to the Hadassah Medical Organization from Russia by her parents after they could not get her diagnosed in their home country. (Her name and those of other patients in the article have been omitted to protect their privacy.) She suffered from unrelieved epileptic seizures and “was weak, undersized and had feeding difficulties,” said Hagar Mor-Shaked, head of the bioinformatics unit in HMO’s Department of Genetics and Metabolic Diseases. “Her parents desperately needed to know why she was born so sick, what therapy exists, what lies ahead for her and whether their future children will be born this way.”

You Won’t Want to Miss:

You Won’t Want to Miss:

When DNA Reveals Hidden Truths: An Online Event

November 18 at 8:00 PM EDT

Hadassah Magazine Discussion Group presents: How Genealogy Became the Great Jewish Pastime, with Executive Editor Lisa Hostein, featuring Dani Shapiro, Jennifer Mendelsohn and Libby Copeland.

Hadassah’s team had the answer a few days later, their quest speeded by a pinpointed search area, advanced technology and new disciplines, such as bioinformatics, the science of collecting and interpreting biological data. “Mutations responsible for 85 percent of human genetic diseases are concentrated in less than 2 percent of the DNA,” said Dr. Orly Elpeleg, head of the genetics department and a world-renowned specialist in identifying the mutations that cause rare genetic diseases. “This 2 percent is the exome, which shrinks the search area from the full genome’s three billion genetic letters to the exome’s more modest 20 million.”

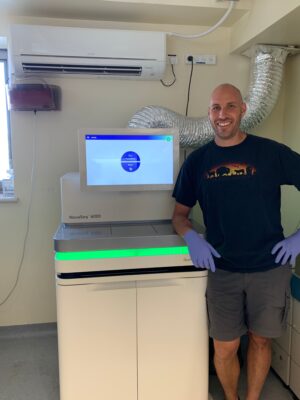

A genetic sample from the sick infant went to Chaggai Rosenbluh in the exome sequencing laboratory on the fifth floor of Hadassah’s Round Building, currently part of a renovation fundraising campaign. To perform his examination, Rosenbluh used a NovaSeq 6000 sequencer, acquired a year ago through the generosity of Judy and Sidney Swartz of Boston, its outward appearance little different from a large paper shredder or small washing machine.

“It linked the baby’s condition with mutations in a gene known as UGDH,” said Mor-Shaked. “We identified it as a new pathogenic gene,” and added it to the Hadassome database. International gene matching found 25 other people affected by mutations in this gene.

Hadassah’s identification of this disease-causing gene brings its total of such found “typos” to 105 since launching the Undiagnosed Patients’ Program 15 years ago. The program’s findings are now gathered in Hadassome. “When we find no match in Hadassome, we know we’re dealing with a new variant,” said Mor-Shaked. “The database, together with our experience in identifying genetic variants, makes us more proficient than most at recognizing a new pathological gene.”

Hadassome, named by Mor-Shaked (who combined Hadassah and exome), has substantially upgraded the speed and competence of a team that was already among the world’s most successful gene hunters. Although the exome database is dwarfed by gnomAD, the Genome Aggregation Database of the Broad Institute in the United States, it is nevertheless sought worldwide, particularly for its extensive records on the exomes of those of Middle Eastern origin.

There is no cure for the baby from Russia, not even a name for her disease, but the diagnosis has put her family in a totally different place, said Mor-Shaked. “They have a medical explanation for their tragedy. They now know that their chances of other affected children are 25 percent in each pregnancy, and that the problem can be diagnosed both preimplantation with in vitro fertilization or prenatally.”

Very occasionally, a genetic disease has an effective treatment. Several years ago, a despairing mother consulted Dr. Elpeleg about her 3-year-old daughter, who had lost all movement in her arms and legs following multiple flu-like infections. Exome examination revealed an unknown variant on gene CD59—found to be shared with three other Israeli families, all, like the patient, of North African descent. “Because of the feverish colds, we suspected the mutation was tampering with the body’s immunological response,” she said. Hadassah immunologist Dr. Dror Mevorach recommended the immunological medication Eculizumab. “It not only halted her paralysis,” said Dr. Elpeleg, “it reversed it.”

Eculizumab is a therapy, not a cure, she stressed. The child will need it for the rest of her life. Nonetheless, she is fortunate. For 95 percent of genetic diseases, there is no effective treatment, only prevention. Here, too, exome analysis and Hadassome are playing a key role.

Nine months ago, Hadassah Mexico, an active branch of Hadassah International, arranged for HMO researchers to examine the exomes of 152 young men and women in Mexico’s Syrian Jewish community as part of an outreach initiative called the Mexican Jewish Community Project. The project was prompted by the illness of a young community member whose rare genetic disease was diagnosed by Dr. Elpeleg. The genetic information found through the project has been added to Hadassome and will be used to help Jews worldwide.

“We found life-changing information in their genes,” said Dr. Elpeleg of the Jews of Syrian descent in Mexico. “In five couples, both partners carry the same disease-causing variant. Another three people harbor serious mutations. All now know to monitor future pregnancies so that unborn children with severe disease can be identified. We also found nine people with genetic variants predisposing them to heart arrhythmias or cancer. All are aware of the necessity of early detection.”

Exome sequencing and analysis are now being used to monitor high-risk pregnancies. “To date, we’ve performed over 400 prenatal exome analyses looking for chromosomal or genetic disorders in unborn children,” said Mor-Shaked. It was this more sensitive test that was used last year for a married Israeli Arab couple who are cousins and who came to consult with the Hadassah team. The couple had one healthy son in his 20s, but their five other children never reached their first birthday.

Read More: How Genealogy Became the Great Jewish Pastime

“Unions between cousins aren’t unusual in traditional Israeli communities,” said Mor-Shaked. “This often leads to damaging congenital syndromes in their children. We had DNA in the database from this couple’s deceased children, and with the mother pregnant again, we were able to identify a mutation in the BRAT1 gene—a genetic misprint that makes a baby rigid and sends it into intractable seizures.”

Exome sequencing found that, although the fetus is a carrier of the culprit gene, the child inherited only one copy and will not suffer the disease that killed his siblings, known as lethal neonatal rigidity and multifocal seizure syndrome. The relieved couple went ahead with the pregnancy and a healthy boy was born in early March. Future pregnancies, if any, will probably use preimplantation genetic diagnosis.

Within a few years, predicted Mor-Shaked, “giving a DNA sample will soon become as routine as having a blood test, and we’ll constantly enlarge Hadassome.

“As the database grows, its applications will grow, too,” she continued. “New answers will be available for those as yet undiagnosed. We’ll be able to study the genetics of more complex diseases, of drug reactions and learn why, for example, general anesthesia is unsafe in some patients. Hadassome will help us find solutions that change lives for the better.”

Wendy Elliman is a British-born science writer who has lived in Israel for more than four decades.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply