Family

When a DNA Discovery Belongs to the Whole Family

Almost two years ago, my 80-year-old bachelor brother called to read me a letter he received from a woman who believed he was her birth father. The letter set out detailed information about her adoption and the DNA evidence of their biological relationship. The news should not have been the shock it was, given my brother’s lack of aptitude for monogamy and the era during which the assignation leading to her birth would have taken place. My brother’s reaction was scorn. He believed that he was likely being extorted and stated that even if he had fathered children, he wanted nothing to do with them. He swore me to secrecy about the letter.

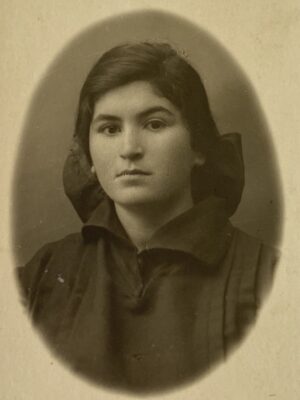

All photos courtesy of Joan Kato.

Soon after the initial bombshell, I started my research. Years before, my husband, one of our two sons and I had sent spit samples to 23andMe. The results were no surprise: I came out 99.9 percent Ashkenazi Jewish; my husband, 99.9 percent Japanese; and our son, 49 percent Japanese and 49 percent Ashkenazi Jewish. I went back to my 23andMe records, sent in a new spit sample for good measure and opted to disclose my identity to DNA relatives on the website. The results of those DNA matches were unequivocal. My closest matches after my son were to two women who had to be the daughters of my only brother. Subsequent googling revealed that both my nieces—whom I will call Maya, the woman who had sent the letter to my brother, and Evelyn—were born in 1970 in the Upper Midwest city where my brother then lived. I told my brother about the indisputable genetic record. It did not alter his attitude.

When my brother was growing up, young men were supposed to get as much “action” as they could with “loose women” in order to hone their skills for their future, uninitiated wives. Good girls were expected to resist the sexual advances of boys, even if they were open to having their comme il faut resistance conquered.

There was an additional sociological dimension. In our Midwestern town, as was likely the case elsewhere, Jews and Gentiles did not generally mix socially. And they were certainly strongly discouraged from dating by both sides. The admonition to many Jewish boys was “sleep with the shiksas [a disparaging term for non-Jewish women] but marry a Jewish girl.” It wasn’t just a Jewish thing. When my brother impregnated one woman—years before the birth of the two nieces I know about—her father stopped insisting that my brother marry his daughter after learning my brother was a Jew.

Within a month of receiving my DNA matches, I told my middle-aged sons about their newly discovered first cousins. Both were stunned, then interested, but not in a hurry for a meeting. One remarked that his DNA overlapped to some extent with every human who had ever walked the planet. The other son urged caution in establishing contact. He perhaps worried these newly found relatives could somehow take advantage of me.

I did not say or do anything for months. But, from the start, I felt an emotional tug toward these women. They were not only my brother’s daughters; they were also my nieces and, important for me, my father’s grandchildren. My father loved nothing better than being a grandfather to my two children. No doubt, he would have relished every moment with these other grandchildren. The discovery of my brother’s daughters was not his story exclusively. It also belonged to our whole family.

Read More: How Genealogy Became the Great Jewish Pastime

My parents were Holocaust survivors. My brother was 9 months old in September 1939 when our parents fled with him from Warsaw toward the East. For the duration of the war, they were itinerant refugees in Soviet Central Asia. My mother became pregnant with me in Kyrgyzstan three months before the war ended. They already knew that my father’s two younger sisters, along with 17,500 other Jews, had been stripped naked on a November night in 1941 and shot dead into a pit by the Nazi’s Einsatzgruppe C. My aunts’ lives were taken before they had time to have any children. My bedridden grandmother died a day later. (My mother’s parents and siblings had long since immigrated to then-British Palestine, where the majority of their children and grandchildren still live.)

We four made it to the United States late in 1947, after a stay in a displaced persons’ camp. My mother never recovered from illnesses acquired during the war. She died in 1951 without reuniting with her family in Israel.

So what was holding me back from reaching out to Maya and Evelyn? Secrecy no longer made any sense. My nieces, one son, many of our cousins and I had already opted for disclosure on 23andMe. Our relationships and overlapping DNA were available to all of us.

Eventually, Maya was brave enough to send me a message through 23andMe.

“Please know that I do not wish to disrupt anyone’s life,” she wrote. “I simply feel compelled to find some answers about my heritage, genetics and some closure to not knowing my biological parents after all of these years. It is increasingly important to me and I realize that time may be running out. Learning that I am 49 percent Jewish was a surprise to me and I’m sad that I know nothing of that heritage, for myself or my children. What my ancestors may have gone through, where they came from, the story of my birth family’s immigration, pictures of my ancestors, are all of interest to me.”

I was overwhelmed. Maya instantly became a visceral reality. I felt compelled to tell her as much about our common heritage as she wanted to know, but I faltered, giving her only the barest outline about myself and our family’s history. I gave her no information about her father. Looking back, my letter was cruelly circumspect.

“Of course, your wish to learn as much as you can about your origins is most understandable,” I wrote. “I do not feel, however, that it is my place to give you many details about my brother. At least at the moment, I prefer to allow him to make his own decisions regarding any communication with you.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Consumer Genetic Testing

Maya’s response to a second, slightly more generous letter I sent dissolved all remaining hesitation. She described her personality traits at length and in detail. What she wrote could have been me describing myself (with the exception that she is fastidious about grooming). I was gobsmacked.

Any resistance to Evelyn had not yet been tested. Then, in July 2019, I received a very brief message from her through 23andMe. She didn’t know my brother’s name and had very little information about him. Once again, I was stingy with information, and told her to ask her half-sister, Maya, for their father’s name. I did, though, give her my email address and phone number. She asked if I would be open to talking on the phone, and I agreed.

At the appointed time, I initiated the call. After I opened with a rehearsed, cheery, “Hello Evelyn, how are you?” she replied, “This is the first time I’ve heard the voice of any blood relative. I am nervous and overwhelmed.” Her statement touched me deeply. We chatted and laughed together for almost two hours. It was my turn to be overwhelmed with gratitude.

I have since met both nieces in person. They never disappoint. Both are lovable, authentic and intelligent. They are also funny and laugh at my jokes, even when theirs are funnier. Evelyn, who lives in Southern California, is a clone of my brother in features and coloring. Maya, who lives in the same Midwestern city where she was born, looks more like me. We will stay connected.

As Jews, we are admonished to keep alive our heritage l’dor v’dor—from generation to generation. I delight in telling my nieces about their Jewish grandparents and great-grandparents and sending them old photos. We now visit on Zoom for a couple of hours every Thursday night. As soon as travel conditions permit, I will take them on a trip to Israel and introduce them to their large family there.

Last year, for Hanukkah, I made latkes for Evelyn, partly in homage to my own aunts. I plan to do the same this year depending on the availability of rapid Covid-19 tests leading up to the holiday.

It would feel wrong to let go of Maya and Evelyn as nothing more than the technical output of 23andMe. I cannot account for my brother’s mindset. I hope it will change before time runs out. In the meantime, Maya and Evelyn are 49 percent Ashkenazi Jewish, and 100 percent my nieces. I can love them and be accessible to them regardless of how they choose to view the future of our relationships or how they judge the significance of their Jewish DNA.

And perhaps my greatest naches comes from watching my nieces, who were strangers to each other, become the loving sisters they are today.

Joan Kato is an attorney. She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her husband of more than 50 years.

You Won’t Want to Miss: When DNA Reveals Hidden Truths: An Online Event

November 18 at 8:00 PM EDT

Hadassah Magazine Discussion Group presents: How Genealogy Became the Great Jewish Pastime, with Executive Editor Lisa Hostein, featuring Dani Shapiro, Jennifer Mendelsohn and Libby Copeland.

Read More: A Pilgrimage Through Ancestral Lands

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Judy Labensohn says

This is such a gorgeous beautifully written story. Kudos to Joan Kato for her courage adventurous spirit and generosity of love.

David Farkas says

This is a beautiful and deeply moving narrative. Especially compelling is the idea that one of the important reasons for Joan Kato to embrace Maya and Evelyn is that Joan’s aunts, murdered by the Nazis, never had a chance to have children of their own.

Beverly Hanlon says

Well, Joan, this is a wonderful story, like your life. Your nieces do look like you and I love that you give them credit for their humor when yours is so delicious. How lucky to have met them and formed a bond. Love you and Hiroki.

Sara Peterson says

Such a beautiful and touching story, and a real-life fairy tale. How enriched all of your lives are from this fortuitous discovery. Thank you so much for sharing it with us.

Tom Pinto says

How wonderful! Thank you for taking the time to share this. Big happy smile here.

Essam Helmy says

Amazing story. Very touching. Happy that you are United again for G-D is good.

It reminds me of my family when theywere kicked out of Egypt during Nasir rule. He took all their positions, villas , stores, and out we left Egypt to Germany .

Joel Kessler says

Joan, I wanted to thank you personally. As a result of your article, I took another look at the Ancestry DNA test that I took 11 months ago and contacted an individual whose name I didn’t recognize who was listed as being my first cousin. His very first question hit me like a ton of bricks. “I don’t know if we are related but did any member of your family run a miniature golf course in Asbury Park, NJ?” The answer was yes but the question was way too personal to be coincidental. After giving me more information and after taking another look at my DNA test and DNA tests of other relatives, there was no question that he was my father’s half brother, my half-uncle! Like your story, my grandfather had had a child out of wedlock. We had our first skype session last Sunday and he bears a very strong resemblance to my father. We have scheduled a Zoom meeting so that the rest of my family can meet him and his family.