Family

Feature

How Genealogy Became the Great Jewish Pastime

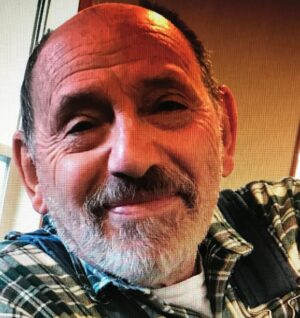

When Stephen Foster took a DNA test on a lark, finding out that he was one-quarter Ashkenazi Jewish was a little like discovering an emu in his Kentucky backyard. In this remote, depopulated corner of Appalachia, where nearly every family traces its ancestry to the British Isles, Jewishness is as exotic as coal mining would be to Manhattanites.

“I thought it was cool,” recalls Foster, 42, who runs an RV campground in Harlan County and speaks with a Southern drawl. “I was raised religious—Christianity—with a church service that was based on first-century synagogue worship. The very first Christians, they were all Jewish! Now I can look at Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and say, ‘Yep, those are all probably ancestors,’” he says with evident wonder. “But obviously, I was stumped. Where in the world did I come from?”

It’s a question people have been asking since roughly the time of Abraham. For most of the millennia, tracing one’s ancestry was a tedious enterprise involving oral histories and, where available, paper (or papyrus) trails. Still, discoveries like Foster’s would have been impossible even 10 years ago. Home DNA tests, Facebook groups, online archives and instant global communication are collectively transforming the once-painstaking craft of genealogy—especially for Jews, who face the additional challenges of a scattered yet genetically interwoven Diaspora.

“Americans in general and Jews in particular are interested because they have more complex and unexpected family ancestries,” says Dr. Jeffrey Malka, 80, a retired orthopedic surgeon in Vienna, Va., who is considered the pioneer of Sephardi genealogy. “America is a country of immigrants. Most people don’t even know where their grandparents are from. And there’s a lot of family mythology that is not necessarily true.”

“America is a country of immigrants. Most people don’t even know where their grandparents are from. And there’s a lot of family mythology that is not necessarily true.”

Into this uncertainty comes the raw truth of DNA results that have upended many families’ assumptions about fundamental aspects of identity. “Genetic identity wasn’t even a concept 60 years ago,” observes the journalist Libby Copeland, author of the recently published The Lost Family, a deeply reported look at the impact of DNA discoveries. “Now there’s an easy way of finding out, and it costs 99 bucks.”

Spit in a tube and a few weeks later you’ll know what countries your forebears came from and whether your parents and siblings are truly biologically related to you. Grandparents’ engagement announcements and long-forgotten ex-husbands are just clicks away online. In 2013, genetic sleuths had only around one million DNA samples for potential matches; today that number is about 35 million, spread across four major databases—Ancestry, MyHeritage, FamilyTreeDNA and 23andMe. But as genealogists will tell you, these are only the building blocks of a larger narrative that takes patience and diligence to fully construct.

For Foster, that meant turning to Facebook groups about three years ago, after the discovery that his paternal aunt was only a half-sister to his father. His father, William Riley Foster, subsequently tested as 50 percent Ashkenazi Jewish—“the first Jewish person I ever met,” the son jokes. Shortly afterward, Stephen Foster connected with Jennifer Mendelsohn, a journalist and professional genealogist who also helped to decipher the hidden non-Jewish paternity of memoirist Dani Shapiro. In her best seller Inheritance, Shapiro details the discovery that her parents had dealt with her father’s infertility by using sperm from a non-Jewish donor, which explains her Nordic looks and a lifetime of “funny, you don’t look Jewish” comments.

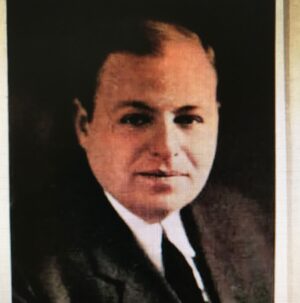

In Foster’s case, Mendelsohn compared DNA matches with online newspaper archives to identify Foster’s grandfather as Dr. Morton Reese, a Philadelphia physician recruited to work at the Harlan County hospital during World War II. As a young man, Dr. Reese had changed his name from the more Jewish-sounding Mordechai Cohen.

Read More: When a DNA Discovery Belongs to the Whole Family

Like so many secrets, the illicit affair between Dr. Reese and Foster’s grandmother—who was married at the time to the man whom Foster always considered his grandfather—would never have come to light were it not for the innovation of $99 DNA test kits. And Foster would never have found himself making challah, latkes and even cholent, inspired by a newfound closeness with his second cousin in Philadelphia, the daughter of Dr. Reese’s child from a first marriage.

“I look just like my Aunt Ruth, if I were to wear a wig,” marvels Foster of the family resemblance, including the distinctive cheekbones he has passed down to some of his four children. In addition to exploring Jewish foods, Foster also has been collecting pebbles to put on the graves of his newly discovered Jewish ancestors once the restrictions around travel open up and he is able to visit Philadelphia for a family reunion of sorts.

Identity-altering surprises, of course, are the exception. Most amateur genealogists are drawn in by motivations less provocative but no less personal: curiosity about gaps in family lore, or a desire to find branches of the family lost to war, migration or the Holocaust.

Some start casually and just keep going. Such has been the case with Schelly Talalay Dardashti, 73, of Albuquerque, N.M., moderator of the Facebook Jewish genealogy group Tracing the Tribe. She started researching family history for her daughter’s 1990 bat mitzvah and eventually traced her mother’s side back to 14th-century Spain. Others are seduced into quests. Marcia Levy, 73, a retired teacher in Palm Beach, Fla., heard from a young man who thought she was his cousin. DNA revealed the man’s biracial father to be the secret son of Levy’s widowed grandfather, who’d had a late-in-life affair with his Black housekeeper.

Steve Stein, president of the Jewish Genealogical Society in New York, was inspired by a 1977 New York magazine review of Dan Rottenberg’s Finding Our Fathers, one of two titles Stein credits with birthing the American Jewish genealogy movement in the 1970s. (The other is From Generation to Generation by Arthur Kurzweil, who in 1977 founded the society, the first of many such groups around the country.) “These two books said, ‘You can do this. Not all the records were lost in the Holocaust,’” as had been widely believed, Stein says.

You Won’t Want to Miss: When DNA Reveals Hidden Truths: An Online Event

November 18 at 8:00 PM EDT

Hadassah Magazine Discussion Group presents: How Genealogy Became the Great Jewish Pastime, with Executive Editor Lisa Hostein, featuring Dani Shapiro, Jennifer Mendelsohn and Libby Copeland.

In the 1970s, fledgling Jewish genealogists were doing research the old-fashioned way. They sat in library cubbies and scrolled through microfilms of records compiled by the National Archives, where Ellis Island passenger lists had been indexed, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, which had collected vital records from around the world. (As a relatively new sect, the Mormons, as they are colloquially known, identified ancestors—including, controversially, of many Jews—in order to baptize them posthumously.) “If the Mormon library had a microfilm archive of the vital records for a particular town in Poland or Hungary, there was a good chance your ancestors might be on it,” explains Stein, 71, a retired computer scientist in Highland Park, N.J.

Read More: A Pilgrimage Through Ancestral Lands

Stein was drawn to genealogy in his 20s, as he was becoming more religiously observant. “I found my religious Jewish ancestors and became way more Jewish than my parents were by embracing that identity,” says Stein. The search for identity, he reflects, is at the heart of most searches. “And then for a lot of people, it’s a fascinating puzzle. There’s never an end; you can always go back one step further.”

As recently as the 1990s, genealogy remained a niche interest, like stamp collecting. Dardashti, a journalist in Israel at the time, recalls an editor at The Jerusalem Post asking her, “Who’s interested in dead people?” The answer: A lot of readers, to judge from the faxes and letters that poured in in response to Dardashti’s genealogy column, “It’s All Relative.” The column later migrated to Facebook, where it became Tracing the Tribe—and a world unto itself for its almost 36,000 members. Every black-and-white wedding photo, Russian immigration document or gravestone closeup kicks off a discussion: Can anyone help translate this? Would “Gata” have been a name, or is it a sloppy rendering of “Gala”? Any other Rosens out there from Dvinsk?

One of Tracing the Tribe’s youngest members is Daniel Breslow, 20. “Ancestry had a free 14-day trial, and I was bored one day,” says Breslow, a Georgetown University political science student, explaining how he stumbled into family research as a teen living in Wyckoff, N.J. While genealogists as a group skew toward retirement age, Breslow is typical of younger sleuths in his enthusiasm for digital detective work: “The fun part is going down rabbit holes on the internet and finding new ways to answer difficult questions.”

For the past five years, Breslow and his newly discovered cousins have scoured open-source websites like geni.com as well as European archives. Most of these cousins—who live in places as far-flung as Washington State, Iowa, Russia and France—are decades older than Breslow, “and I’m the most adept at using a computer creatively,” he explains.

Their research revealed that a great-uncle long believed to have perished in Siberia actually survived, changed his surname and became the Yiddish playwright Mark Daniel. Daniel, in turn, spawned an illustrious line in Russia that included the writer and dissident Yuli Daniel, along with Breslow’s cousin, Alexander, a human rights advocate with whom the young American has chatted on Zoom.

“DNA is an absolutely revolutionary tool in the genealogist’s toolbox”

“DNA is an absolutely revolutionary tool in the genealogist’s toolbox,” says Mendelsohn, the journalist/genealogist, noting that’s especially true for Ashkenazi Jewish families, for whom the paper trail can be elusive. “In many parts of Eastern Europe, there simply aren’t records going back before the late 18th or early 19th century,” she explains. It was only around that time that Ashkenazi families began using surnames—and not that many names, either. “Believe it or not, there were many, many Abraham Goldenbergs married to Miriam Weinbergs all across Eastern Europe.”

DNA, in contrast, is unique to every person. Mendelsohn has used lists of distant matches to find relatives believed to have died in the Shoah, to reunite adoptees with their biological families and to discover, in her own case, three previously unknown siblings of her great-grandparents. “Before DNA, I could have traced every Fleischman family in America with ancestry in the Russian Empire, which is all the information we had about my great-grandmother—her maiden name. But the DNA matches were miraculous,” Mendelsohn recalls, explaining that DNA websites connect users with others whose genetic profiles show a degree of biological relationship. Once in contact, relatives can share their respective information: Did Great-Aunt Rose have a sister? Whatever happened to that younger brother during the war? Which borough of New York did they live in? “It’s like putting together a huge puzzle,” Mendelsohn adds.

Yet as Copeland documents in The Lost Family, DNA discoveries can be a mixed blessing. Our early 21st-century moment straddles a time of secrecy—when people could reasonably expect to conceal an affair, sperm donation, even adoption—and a new era of openness and candor that takes many by surprise. For the approximately one in 30 people cited by Copeland and others who discovers a genetic mismatch with immediate family, “the experience of discovering that you’re not exactly who you thought you were is indelible,” Copeland says. “It can be a trauma that you live with for the rest of your life.”

In the course of her research, Copeland has witnessed the gamut of reactions—from angry family ruptures to enthusiastic integration into a biological family and a newfound ethnic identity. For some people who discover they are Jewish, “there’s this extra layer of meaning to it,” she says, with many finding themselves drawn to Jewish life. Alice Collins Plebuch, a central figure in The Lost Family, was raised Irish Catholic yet joined a synagogue book club after discovering her father was born Jewish. Copeland documents how Plebuch learned through a DNA test that her heritage was half Ashkenazi, leading to years of meticulous yet often confusing research that revealed that Plebuch’s Jewish-born father, Jim Collins, had been accidentally switched at birth in a Bronx hospital with an Irish baby. The two men had unwittingly grown up in the wrong families.

The explosion of DNA kits and genealogy websites coincides with a climate of increased racial and ethnic awareness in America. “There’s a desire to have a more specific kind of identity, and even a modicum of interraciality, something that distinguishes people from being merely white,” notes Copeland. But cloaking oneself in the exoticism of a minority identity without grappling with its lived experience can be problematic: Witness the backlash to the (very white) Elizabeth Warren’s claim to Cherokee ancestry, confirmed as a minor link through DNA.

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Consumer Genetic Testing

At the same time, people with even small percentages of Jewish or African-American ancestry, for example, tend to identify more strongly than bloodlines would suggest. “There’s a real sense of wanting to claim the ethnicities that feel more endangered—the thing that was almost eradicated from the Earth,” reflects Copeland, who, with a single Jewish parent, counts herself part of the phenomenon. “There’s a specialness, a way to distinguish yourself and your individual story.”

Genealogists, who take the long view, can dispel that specialness. “If you go back a few hundred years, you have more ancestors than existed people on the planet. How can that be? Very simply, it’s the same individuals occurring repeatedly back and forth,” explains Dr. Malka, noting that those individuals appear as differently labeled ancestors on the same family tree—as, for example, a fifth cousin as well as another relative’s great-great-niece. Historically, many Jewish communities practiced endogamy, or in-marriage; 40 percent of Ashkenazi Jews are descended from just four European woman who lived 1,000 years ago, according to research released by Israeli scientists in 2013. “We’re all related,” is Dr. Malka’s conclusion. “You want to find out if you’re descended from King David? Guess what! You are.”

Stephen Foster with his wife, Jenny (left), his father William Riley Foster (center) and grandfather Dr. Morton Reese (right). All images courtesy of Stephen Foster.

Dr. Malka himself comes from a line of Sephardi rabbis with roots in 13th-century Aragon and Catalonia. Born in colonial Sudan and raised in Switzerland, Dr. Malka became interested in genealogy while helping his father, the son of a Moroccan rabbi, to write his memoirs in the late 1990s. At that time, Jewish genealogy was dominated by Ashkenazi Jews. Dr. Malka applied his rigorous scientific approach to Iberian archives, and the result was Sephardic Genealogy: Discovering Your Sephardic Ancestors and Their World, originally published in 2002 and now in its second edition.

Sephardi research, he points out, is a radically different proposition. Unlike Ashkenazim, Iberian Jews used surnames, and their records go back a thousand years in Spain’s national archives. “It’s so-and-so borrowed money from so-and-so, so-and-so sold his house to so-and-so, that kind of stuff,” Dr. Malka explains. “Everyday people. If you were arrested or you died and left an estate, it will be in those records.” At some point, individual ancestors are less compelling than the portrait that emerges of a vanished society. “Your family simply becomes a tool to learn the history.”

For American Jews, genealogy is a way to reclaim that history—a rich linguistic, religious and cultural heritage that, for many, was lost to the pressures of assimilation. On JewishGen, the largest Jewish genealogical database, dozens of special-interest groups and virtual kehillahs are dedicated to reviving the memories of far-flung shtetls and cities in Europe where prewar Jewish culture flourished. “People want to know more about the legacy of their own family, and how they fit within the Jewish people and community,” says Avraham Groll, JewishGen’s executive director. “They want to know what it is that they should be transmitting to their own children and grandchildren.

“It’s not just about names and dates,” Groll adds. “It’s about how people lived, and what lessons we can ultimately learn from them.”

How to Get Started on Your Family Tree

Experts advise collecting basic information by first interviewing older relatives (find a useful template here). Next, confirm data using the 1940 United States Census, the most recent year publicly available, which is a font of useful demographics, from household members to countries of birth. The National Archives digitized most censuses going back to 1790.

The four major DNA testing companies offer tools to find relatives and allow registered users to create and share online family trees. They are Ancestry.com, the world’s largest for-profit genealogy database; MyHeritage.com, an Israeli outfit, which helps newbies find and organize vital records; 23andMe.com, which analyzes both ethnicity and genetic health; and FamilyTreeDNA.com, which runs various types of DNA tests for maternal and paternal lines.

JewishGen.org, an affiliate of New York City’s Museum of Jewish Heritage, bills itself as “the global home for Jewish genealogy” and has more than a half-million registered users worldwide. Its vast online databases, hosted by Ancestry, include a Family Finder compilation of surnames and towns with more than 500,000 entries. Content skews heavily Ashkenazi (JewishGen says it is improving its Sephardi resources) and works best for those with a basic idea of where and whom they descend from.

SephardicGen.com is Dr. Jeffrey Malka’s clearinghouse for tools and resources aimed at families with roots in the Iberian and Mizrahi Diaspora—including Western Europe, the Balkans, the Middle East, the Americas and beyond.

To connect with others working on family histories, consult the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies to find a local Jewish genealogy society or join a Facebook group (the largest are Tracing the Tribe and Jewish Genealogy Portal). Jennifer Mendelsohn is the administrator of the Facebook group Jewish DNA for Genetic Genealogy and Family Research. With almost 8,000 members, it is the largest Facebook group dedicated to matters of Jewish DNA.

Hilary Danailova writes about travel, culture, politics and lifestyle for numerous publications.

You Won’t Want to Miss: When DNA Reveals Hidden Truths: An Online Event

November 18 at 8:00 PM EDT

Hadassah Magazine Discussion Group presents: How Genealogy Became the Great Jewish Pastime, with Executive Editor Lisa Hostein, featuring Dani Shapiro, Jennifer Mendelsohn and Libby Copeland.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Marilyn Y. Robinson says

I have a “Fleischman” ancestor in my tree–my maternal 3rd great grandmother, Jachetty/Jacheta FLEISCHMAN, (b. 1812) married to Benjamin Leyba (Leib) REGENT. (possibly married in Krakow in 1828) Her daughter, Malka (Molly) Tauba was born in Krakow in 1834; & her son, Izak Dawid, was born in Krakow in 1838.

Also, FTDNA says that I have a 2-3rd cousin, Paul MENDELSOHN, but I don’t know anything about the potential family relationship.

Is Mendelsohn, Jennifer Mendelsohn’s surname or maiden name?

Naomi C Altschul says

We are planning to present a 4 monthly programs about Jewish Genealogy and after reading the wonderful articles in Hadassah Magazine, we are wondering if Hadassah has any suggestion for a guest speaker.

Naomi Altschul and Jane Gordon

Tamar Hadassah

Palm Isles

Boynton Beach, Fla

Peninah Zilberman says

Great article,

As a follow up to the family tree research, once you have enough basic materials and knowledge, I highly recommend , planning a “Family Roots/Routes Journey”. It has many rewards…except of the “Togetherness”, many family stories and issues are coming up when the family members are away on neutral landscape, country, closing circles, getting the synergies of the local site, and finding the unknow until then…just to name a few…all is based on the many travelers I have lead since the eastern block has opened to Jewish Tourism….now is the time to plan your Family Journey

Tarbut Sighet provides such services for Romania – during May-Oct. 2023