Food

Personality

Michael Twitty’s Kosher Soul

Michael Twitty knows how to command an audience, something I learned firsthand when I attended his keynote presentation at the 2018 Hazon Food Conference, an annual gathering of socially conscious Jewish foodies.

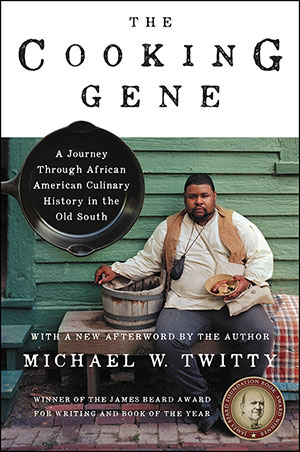

Along with almost 150 others, I was transfixed as Twitty—who is Black, gay and Jewish—elegantly wove Jewish and Black metaphors and expressions into tales of his travels throughout the American South and Africa, where he conducted the research at the heart of The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South, his book that had just won the James Beard Book of the Year award.

As he whipped up a batch of his signature Black-Eyed Pea Hummus, he recounted his exploration of African foodways through the harsh lens of slavery, making a cogent argument that the roots of southern cooking lie in Africa.

Even at the time, it struck me as a complex, nuanced and highly current presentation. Now, two years later, as the United States undergoes seismic shifts in identity politics and race relations, the landscape seems even more complicated—and his work all the more relevant.

“We are having a new level of conversation,” Twitty, 43, said from his home in suburban Maryland, where he lives with his fiancé, Taylor Keith. “The imbalance of power, the burden of systemic oppression—all of that is being re-examined right now.”

An outspoken oracle, whether on social media, his own blog, Afroculinaria.com, or on television, he is taking advantage of his growing influence to educate the public. Recently, he guided host Padma Lakshmi through the Gullah-Geechee cuisine of Lowcountry South Carolina as a guest on her streaming show, Taste the Nation. One of his first major teachable moments came back in 2013, when he schooled then-celebrity chef Paula Deen on her use of the “N word” when she was at the height of her fame.

“As a Jew, I extend the invitation to do teshuvah—which means to repent—but better—to return to a better state, a state of shalem—wholeness and shalom—peace,” Twitty wrote to Deen at the time in a widely read “open letter” on Afroculinaria. “This is an opportunity to grow and renew.”

Twitty instinctively understands generational shifts, especially as they relate to the South and race relations. His paternal grandmother, Eloise Booker, had worked as a domestic for a Jewish family in Washington, D.C.

“She used to cook all the foods for Passover and tell me a bit about it,” said Twitty. “She was a very good cook and the family she worked for acknowledged that.”

As a child, he loved watching television cooking shows and anything related to food. Frank’s Place, a cult one-season hit starring Black actor Tim Reid as a professor who inherits a New Orleans eatery, provided early inspiration, as did the book and movie versions of Julie and Julia, the story of a woman who found personal and professional salvation by cooking her way through Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking. “I started my blog (in 2012) right after seeing that movie,” said Twitty.

Also from a young age, Twitty was attracted to Judaism. He grew up in Silver Spring, Md., near Kemp Mill, a hub of observant Jewish life. “I knew white Jewish kids,” he said, “and we all went to the same schools back then.”

His mother, Patricia Townsend, who died in 2014, was familiar with challah from her hometown of Cincinnati, where she would buy it on her way back from church for Sunday supper. In Maryland, she bought fresh-baked challahs on Friday. “She would toast it and serve it with blackberry jam, apple butter—all that southern stuff,” Twitty recalled.

In his early 20s, Twitty said, he found a second home in a nearby synagogue. “That was one of the few places I could go where I felt like my complete self was being nourished,” said Twitty, who converted at age 25. When asked about his conversion, he declined to give details. “How I have remained a part of the community that has a fluctuating relationship with race and the LGBTQ community is more interesting to me than a dip in the mikvah some 20 years ago” he told me.

Being Black and gay as well as Jewish can sometimes make him a triple outsider of sorts. “It’s not often that I get to be my whole self,” said Twitty. He recalled a speaking engagement at a senior day care center in Baltimore, where “the Black people only wanted me to talk about Black issues and the Jewish people only wanted me to talk about the Jewish stuff. That is my life.”

Yet by seeking to amplify his own voice and polish the facets of his own identity, he has turned marginalization into validation, bringing people from different walks of life into his fold.

Yet by seeking to amplify his own voice and polish the facets of his own identity, he has turned marginalization into validation, bringing people from different walks of life into his fold.

“He has become an important voice at an important time,” said Joan Nathan, doyenne of the Jewish food world, who first met Twitty when he approached her at a cooking demonstration in the late 1990s. Nathan invited Twitty to her home, where they baked challah together. “The rest is history,” she said. “He has brilliantly interpreted the intersection of African American foodways and Jewish foodways. Through his voice he is showing the trauma and experience of African-Americans and Jewish Americans.”

Often, he turns to food history to provide context and healing.

“These are two groups of people for whom very specific foods were introduced into their cuisines not only because they tasted good,” said Twitty. “As outliers of society who were moved about by trade and other forces,” he explained, the availability of certain foods made them popular.

As examples, he cited fish and chips (introduced to Britain in the 1860s by an Eastern European Jewish immigrant) and artichokes (first prepared by Roman Jews in that city’s ghetto nearly 2,000 years ago). “We eat these things because they are part of a larger story,” he asserted.

That story also includes foods of African origin, like okra and benne (sesame) seeds that were appropriated by white southern cooks as their own after enslaved Africans had brought them from their native lands and used them in their cooking.

“Through more honest conversations and coming to terms with the brutality of the slave trade and its connection to foods we eat today,” he said, “we can start the healing process.”

For Twitty, that process includes acknowledging the role Jews played in slavery.

“When I speak about Jewish slaveowners, Jewish audiences are very quiet,” said Twitty, who believes the discomfort interrupts a narrative that Jews were always on the right side of history.

Still, he bristles at how anti-Semites use Jewish slave ownership and involvement in the slave trade as fodder for hatred.

“Were there Muslim slave traders? Were Christians slave traders? Were there even African slave traders? Yes, yes and yes,” he answered.

Twitty is currently working on his second book, Kosher Soul, which addresses his blending of Jewish and Black food traditions (see his recipe for West African Brisket) and also delves into his own Jewish roots. Indeed, DNA research has revealed that he has Ukrainian Jewish cousins.

When I asked Twitty if he experienced particular racism or marginalization in the Jewish world, he answered in his characteristic blend of realism and optimism.

“It depends on the situation. Online is the world where you encounter that all the time, because people are in your face since they have anonymity and protection,” said Twitty. “I try not to engage too much anymore on those platforms.”

Still, said Twitty, “For me, the negative situations that I have incurred cannot and will never outweigh my positive experiences. When we are at our best, we look out for each other. You don’t want any Jew to be alone. To not have a place at the seder table, a place to break the fast. In Judaism, being together is more than just community building, it is human sustaining. You are part of a family.”

Black-Eyed Pea Hummus

Serves 6

1 15-ounce can plain black-eyed peas, rinsed and drained

1/4 cup extra-virgin olive oil, plus more for drizzling

1/3 cup tahini

1/2 cup freshly squeezed lemon juice

1 1/2 teaspoons kosher salt

4 garlic cloves, minced or roughly chopped

1 teaspoon smoked paprika, plus more for garnish

1/2 teaspoon ground cumin

1/2 teaspoon ground coriander

1/2 teaspoon chili powder

1 teaspoon brown sugar or raw sugar

1 teaspoon hot sauce

2 tablespoons minced fresh parsley, preferably flat leaf, for garnish

1 tablespoon sesame seeds, for garnish

1. Reserve 2 tablespoons black-eyed peas. Mash or pulse the remaining peas in a food processor. Mashing makes for a chunkier mix, and processing makes for a smoother dip. If you are using the processor, pulse for about 15 seconds at a time, until the peas are broken down. Continually scrape the sides of the processor so that everything gets mixed in. (While 2 tablespoons of black-eyed peas will work as garnish, for texture, add half a can of whole black-eyed peas to your mashed or processed mixture.)

2. Mix the olive oil and tahini together with a whisk. Turn the black-eyed pea mixture into a mixing bowl and drizzle in the tahini mixture, a bit at a time, mixing between additions until everything is incorporated. Add the lemon juice, salt, garlic, paprika, cumin, coriander, chili powder, sugar and hot sauce; mix well, adding more of the spice mixture to taste if necessary.

3. Transfer the hummus to a bowl. Garnish with the reserved black-eyed peas, then sprinkle with a bit of paprika, the parsley and sesame seeds. Drizzle with extra-virgin olive oil, if desired.

West African Brisket

Serves 10

Recipe from Michael Twitty and Tori Avey

5 pounds first-cut brisket

1 tablespoon kosher salt

1 teaspoon coarse black pepper

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil, divided

1 teaspoon ground ginger

1 teaspoon paprika

1 teaspoon cinnamon

1 teaspoon chili powder

1/4 teaspoon cayenne pepper

3 whole white or yellow onions, peeled and diced

3 whole bell peppers, green, red and yellow, seeded and diced

1, 14-ounce can diced tomatoes

2 tablespoons brown sugar

1 teaspoon prepared horseradish

2 cups low sodium chicken, beef or vegetable stock

2 bay leaves

1 sprig fresh thyme or

1 teaspoon dried thyme

2 whole large red onions, cut into rings

8 whole garlic cloves

Fresh herbs for garnish (optional)

1. Preheat oven to 300°. Rub the brisket with salt and pepper. On the stovetop, heat 2 tablespoons of olive oil in a large Dutch oven, heavy pot or roasting pan over medium-high heat. Brown the brisket on both sides (about 5 minutes per side). Remove brisket from the pan and set aside. Note: If you don’t have a roasting pan you can use on your stovetop, you can do these initial browning and sautéing steps in a large skillet, then transfer everything to a large roasting pan or dish before putting in the oven.

2. In a small bowl, stir together the ground ginger, paprika, cinnamon, chili powder and cayenne. Set aside.

3. Add the white or yellow onions and bell peppers to the oil and fat in the pan (add additional oil if needed). Sauté for another 7 to 8 minutes, until the onions are caramelized and the vegetables are fragrant.

4. Add the diced tomatoes, mixed seasonings, brown sugar, horseradish, stock (broth), bay leaves and thyme to the pan. Stir together and cook for about 5 minutes. Pour the sauce mixture out into a separate large bowl and remove pan from heat.

5. Pour 1 tablespoon olive oil into the pan and coat evenly, then place the red onion rings at the bottom of the pan.

6. Place the brisket on top of the red onions, then top the brisket with the whole garlic cloves. Cover with the cooked tomato sauce mixture.

7. Cover the roasting pan with a lid or foil and place into the preheated oven. Let it roast for about 5 hours. It should take about 1 hour per pound of meat (leaner cuts of meat may take longer—test for doneness). Brisket is ready when it flakes tenderly if pierced with a fork. You can let it cook even longer for a soft, shredded texture if that’s what you prefer. When fully cooked, the brisket will have shrunk in size.

8. Remove brisket from the pan and let it rest on the cutting board, fat-side up, for 20 to 30 minutes. (This brisket can be prepared ahead and left to rest in the refrigerator for up to two days. Go online to hadassahmagazine.org/food for make-ahead directions.) Meanwhile, pour the sauce and vegetables from the roasting pan into a smaller saucepan. Skim fat from the surface of the cooking sauce, then reheat the sauce until hot (not boiling).

9. Cut fat cap off the brisket and discard the fat, then cut the brisket in thin slices against the grain. Serve topped with hot sauce and softened vegetables. Top with fresh green herbs, if desired.

Adeena Sussman is the author of Sababa: Fresh, Sunny Flavors from My Israeli Kitchen. She lives in Tel Aviv.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

BOBBI COHEN says

Where are make ahead directions for West African Brisket

Diane S Berman says

I have the same question. Where are the make ahead directions that are supposed to be at hadassahmagazine.org/food?