The Jewish Traveler

Feature

Morocco, Where Jewish Memory Lives On

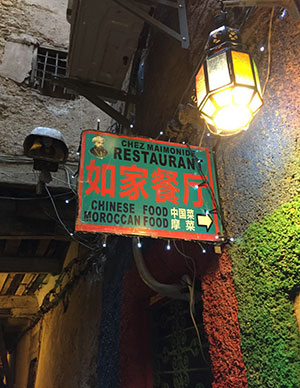

The revered medieval Jewish scholar Moses Maimonides might be turning over in his grave, knowing that the house where he briefly lived in Fez, Morocco, had been turned into a Chinese-Moroccan restaurant.

Or, he might be amused, even pleased, to discover that his legend lives on at Chez Maimonide. Step into the tiny eatery deep in the market of the world’s largest walled city and you’ll find framed portraits of the sage, fragments of Hebrew prayers and even an old one shekel note that bears his image.

Chez Maimonide provides a brilliant metaphor for the history of the Jews in Morocco. It speaks to the rich Jewish culture and influence that once flourished in this North African nation and that in many ways continue to this day, despite the departure of the vast majority of the country’s Jews in the second half of the 20th century.

The complex legacy of the community, which once numbered between 250,000 and 300,000 and now hovers somewhere between 2,000 and 2,500, continues to be probed and rewritten. As a first-time visitor to Morocco, I grappled repeatedly with two key questions: Why did the Jews leave? And why do tens of thousands of Moroccan Jews come back each year to visit this land?

I was part of a Jewish media trip that predated the coronavirus pandemic, which, of course, has shut down travel almost everywhere. It also has hit Morocco’s tiny Jewish population especially hard: At least 12 Moroccan Jews have died from Covid-19, including two relatives of Israel’s economy minister, Amir Peretz.

But local Jewish and tourism officials are optimistic that once the world re-opens, travelers will return to this intriguing land. And when they do, visitors will discover, as I did, not only the poignant remnants of Jewish life here, but also something completely unexpected: the creation of new facilities to encourage tourism from around the world—mostly though not entirely from the Moroccan Jewish diaspora.

Across this nation that mixes African, Arabian and European influences, ancient traditions blend seamlessly with modern conveniences and sensibilities. On many a city street, for instance, you’ll find the inevitable Starbucks, Pizza Hut and Zara alongside outdoor cafes where clusters of older men gather while women in jeans and blouses with stylish hijabs stroll by. From the northern tip of the country, near Tangier, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean, to the often snow-capped Atlas Mountains that stretch the length of the country, to the majestic Sahara Desert, where a camel ride across golden sand dunes makes you feel like a character in Lawrence of Arabia, the country offers a diverse, scenic and adventurous landscape.

And at nearly every turn, it seems, Jews left their mark.

“The Jews were pioneers in so many ways,” said Zhor Rehihil, the curator at the Museum of Moroccan Judaism in Casablanca. She cites such varied examples as the Jewish influence on the ancient Berbers in the Atlas Mountains as well as the fact that Jewish girls were the first of their gender to receive a formal education, thanks to the establishment of the French-imported Alliance Israélite Universelle schools in the last part of the 19th century.

“Even though they left,” Rehihil said, “we still have Jewish memory.”

The memories manifest themselves in many ways, evoking the economic, social and cultural contributions to a society that in some ways still laments the Jewish void. They are articulated, for example, by older citizens like Abdullah, who sits upon a pile of straw in a stall in the charming, blue-washed northern city of Chefchaouen, weaving baskets to affix to donkey saddles. It’s a skill he learned as an apprentice to a Jewish tradesman who, upon leaving the country for Israel, passed on his business, tools and all, to him. “The tradition will die” after he is gone, said Abdullah, who added that he owes much, including his livelihood, to his former boss, whose family still comes to visit him occasionally.

The memories linger in sections of the sprawling souk of Fez’s medina (old city), where most of the gleaming jewelry shops were once owned by Jews. In Fez as well as in the equally colorful Marrakesh market, where stalls selling burlap sacks of spices of all shades and freshly slaughtered chickens mingle with those filled with patterned pottery and household wares, some of the shopkeepers call out to passers-by in Hebrew and carry Judaica items like menorahs or Star of David necklaces, as much a nod to the past as a selling point for Jewish tourists.

And the memories are baked into the elaborate new Moroccan Culinary Arts Museum in Marrakesh, which boasts an entire room dedicated to Moroccan Jewish cuisine. Images of savory harira soup, which is not particular to the Jews but was often part of a holiday meal, and sweet treats like almond-stuffed dates and crescent-shaped cookies known as gazelle ankles line the walls.

Nowhere in the country is the history of Jewish life better captured than at the Museum of Moroccan Judaism. Opened in 1997 as the first museum in all of Casablanca, it was until recently the only Jewish museum in the Arab world, too. (Another Moroccan center dedicated to Jewish culture, Bayt Dakira, which means House of Memory in Arabic, opened in January in Essaouira, an Atlantic coastal town where 40 percent of its population was once Jewish. King Mohammed VI of Morocco attended the inauguration.)

The museum in Casablanca, where most of the country’s Jews now live, boasts a broad collection of Judaica, Torah scrolls, costumes and replicas of synagogue spaces and ritual elements such as sanctuaries, pews and an Ark.

According to Rehihil, the museum provides an opportunity for Moroccans who came of age after what is widely referred to as “the departure” of most of the country’s Jews to begin to understand Jewish contributions to society. She says the museum attracted some 9,000 visitors in 2019, including many Muslim students.

“For my generation and after, we didn’t know Jews,” said the 52-year-old Rehihil, a Muslim woman with a Ph.D. in Jewish studies. “We weren’t in the same schools, in the same quarters, in the same buildings like our parents were.” As a university student studying archaeology and anthropology during the 1980s, at the height of the Lebanon War, all she heard about Jews was related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. “Learning about the conflict pushed me to understand who the Jews were and why they left Morocco.”

Though being Jewish in a Muslim country always presented its challenges, Jews flourished for centuries in many Muslim nations even as they were accorded second-class status as dhimmi. This gave them protection but also subjected them to special taxes, restrictions and, in some cases, violence. As the largest community in the Arab and Muslim world, the Jews of Morocco also experienced a blend of benevolence and degradation but, compared to other nations, they were by and large a successful and highly acculturated community, according to Norman Stillman, a pre-eminent historian on Jewish life in Arab lands.

As Serge Bergudo, an ambassador at large to the king of Morocco since 2007, put it when my tour group met him for lunch at an upscale restaurant atop a Casablanca high rise: “I can’t say the life of Jews in Morocco is all a life of wine and roses.” But, added Bergudo, who also serves as president of the Jewish community in Morocco and a vice president of the World Jewish Congress, the situation both today and historically has always been better than elsewhere in the Muslim and Arab world.

Archaeological evidence of Jewish life in Morocco dates back to Roman times, and Jews settled among—and in some cases, converted—Berber farmers even before the Arab conquest of the land in the seventh century. The expulsion of Jews from Spain and Portugal in the 15th century sent waves of refugees fleeing the Iberian Peninsula. Jewish life expanded in the 17th and 18th centuries. Local Jewish communities were often separated in distinct quarters, called mellahs. (In Arabic, mellah means salt—the first mellah was established in Fez where a salt deposit stood). It was a move meant to protect the Jews as much as to segregate them. Despite the separation, Jewish and Muslim cultures were deeply entwined.

For more than 1,800 years of documented Jewish history, “there’s been a Jewish population that was—and is—extremely embedded in general Moroccan culture; it is part of the mosaic of different ethnicities,” said journalist Kati Roumani, 50, a British-born Sephardi Jew who lives in Marrakesh.

During World War II, when Morocco was a French protectorate subject to the laws of the Nazi-aligned Vichy government, Sultan Mohammed V, who later became king, made clear publicly and privately that he opposed the discriminatory policies. Though Stillman said it may be urban legend that he actually saved the Jews from deportation—there is no evidence that there was a plan to deport the Moroccan Jews—the king still “deserves our praise and thanks.”

By the mid-20th century, after the number of Jews peaked at some 280,000, the population began to decline dramatically due to a variety of factors, according to historians and locals alike. The first wave of departures came between 1948 and 1951, with the establishment of the State of Israel. Most of the Jews who left then did so as Zionists, though some were also prompted by anti-Jewish riots in the north of the country that left 44 dead.

The bulk of the country’s Jews left in the years after Morocco attained its independence from France in 1956. The language and cultural shift from French to Arabic, along with the economic and political uncertainty that independence brought, prompted many to emigrate. From 1961 to 1964, Israel conducted a grand, clandestine aliyah operation, ultimately transporting close to 100,000 Moroccan Jews.

Then, as the Arab-Israel conflict escalated and Morocco aligned with the Arab League’s rejection of Israel, many Jews began to feel increasingly uncomfortable and unsafe. Another wave left in the aftermath of the 1967 Six-Day War. Today, most of the Moroccan Jewish diaspora lives in Israel, Europe and Canada, along with pockets in the United States and Latin America.

Ironically, the most official recognition that Jews are part of the identity of the country came long after most had departed. The preamble to the 2011 Constitution notes that the Muslim nation has been “nurtured and enriched by African, Andalusian, Hebraic and Mediterranean constituents.” Though that mention could be seen as part of the monarchy’s wider efforts to avert the internal strife that engulfed much of the Arab world during the so-called Arab Spring, it also is considered a reflection of King Mohammed VI’s genuine belief that Morocco is more than just a Muslim Arab nation.

That belief, following in the footsteps of his father, King Hassan II, is also reflected in the government’s increasing outreach to local and foreign Jewish communities as well as its involvement in a massive restoration project of synagogues and cemeteries throughout the country. To date, some 15 synagogues and 160 (of a total of 600) Jewish cemeteries have been restored.

It is in some of those very synagogues where the dramatic decline of Jewish life is most palpable. Even Beth-El synagogue in Casablanca, one of the country’s largest Jewish houses of worship and one of a handful still operating in the city, gets just a few dozen local worshipers each Shabbat.

In Fez, home to fewer than 50 Jews, the Roben Bensadoun synagogue in the newer part of the city survives only because of the tourists that fill its pews most Shabbats and holidays. Fewer than 10 local Jews show up each week, and even the rabbi doesn’t usually appear, according to Shalom Turjman, the 60-year-old caretaker. Though the rest of his family has left the country, Turjman stays, he says, because he’s the youngest member of the community and the only one left to take care of the synagogue.

Most of the country’s synagogues are not operational, though some occasionally host a wedding or bar mitzvah for young Jews of Moroccan descent whose families come from abroad. Instead, these synagogues, as well as many cemeteries, serve as part of the culture of Jewish memory—a culture that is being preserved largely by Muslim men and women. These caretakers—once they are tracked down, not always a simple feat—are eager to unlock the gates and welcome visitors. They are quick to open the Arks to display the Torahs or uncover hidden mikvehs. At the cemeteries, they graciously escort the tourists to see the most elaborate tombstones, ones etched with flowers and books and lengthy epitaphs. They proudly provide facts and figures, to the best of their ability, that attest to the rich Jewish heritage.

At the Miara cemetery in Marrakesh, watchman Otman Kanami, along with his brother Khalid, is the third generation of his family to tend to the sprawling expanse of some 20,000 graves. Speaking in Hebrew, he details the history of the local community and opens the door to the massive mausoleum of one of its most revered sages, Rabbi Hanania HaCohen.

“I like to help the Jews,” he said simply, adding that he turns lights on for his Jewish neighbors on Shabbat.

The intermingling of synagogue and cemetery is most striking in the newest Jewish development taking shape in Morocco. Visitors who make annual pilgrimages to the gravesites of revered religious leaders are finding newly constructed chapels, mausoleums, kitchens and even toilets. These pilgrimages, known as Hiloula, have long been a tradition for Moroccan and North African Jews, a ritual they share with their Muslim neighbors.

The starkest evidence of this development is in Erfoud and nearby Rissani, desert towns in the Errachidia Province in eastern Morocco. In May 2019, a new synagogue was opened adjacent to the cemetery in Erfoud, which followed the construction a few years earlier of an ornate mausoleum for Rabbi Shmuel Abuhatzeira, whose burial place attracts pilgrims each year.

During our visit to Erfoud, we met a large group of Israelis davening morning prayers. Their tour guide was Anat Levi Cohen, an Israeli of Moroccan descent who says she generally brings 14 groups each year. Levi Cohen, whose mother still lives in Essaouira, donated the mezuzah at the entrance to the bright, simple but beautifully appointed chapel.

Also at the Erfoud synagogue that day was Reuven Elharrar, who was on one of his twice yearly visits to Morocco. Originally from Casablanca, Elharrar, 62, emigrated with his family in 1970, among the large wave of Jewish immigrants attracted to—and officially welcomed by—Montreal because of its French language and culture. He became Lubavitch after a trip to New York City, where he met the Lubavitcher rebbe. Elharrar says he feels safer now in Morocco, traveling by public bus with his cap, tzitzit and bag with Hebrew writing, than he did when he lived in the country. Then, he says, kids used to steal his kippah and there were occasional incidents of violence against the Jews.

Elharrar has become friends with the man responsible for much of this new construction. Michel Sebag is a Jewish builder from Casablanca who has been hired by wealthy Moroccan Jews, most living in the diaspora, to augment the facilities at cemeteries across the country.

Not all the Jews returning to their roots come on religious pilgrimages. Overhearing Hebrew while dining at my hotel in Tangier one morning, I introduced myself to Ruth and David Anais, an Israeli couple traveling with three of their four adult children. She grew up in Tangier and he in Fez, both members of the Dror Zionist youth movement, which encouraged aliyah to kibbutzim. They left the country as young adults in 1964, a move they kept secret even from their families. After a year in France, they settled on Kibbutz Re’im in the northern Negev, where they married.

Now residents of Ashdod, which boasts the largest Moroccan community in Israel, they insist they experienced no problems when they lived in Morocco and harbor only positive memories that they want to share with their sons. “Why are you leaving?” they remember their neighbors asking back then. As they traveled the country last November, some of their former neighbors still asked the same question. “I want to live in my country, Israel,” they each answered.

But the ties remain strong: Ruth Anais is part of the Always Tangier Facebook group, which keeps her connected to the land of her youth.

While no one expects those who left to come back and live here—though a small number are doing so—the constant flow of Jewish visitors provides an important sense of connection and reassurance for the tiny number of Jews who continue to make Morocco their home.

That kind of connection only confirms communal leader’s Serge Berdugo’s long-held belief: Once a Moroccan Jew, always a Moroccan Jew. Traveling across the land, you don’t have to be Moroccan to understand that pull.

WHAT TO SEE AND DO

Morocco is a traveler’s delight, with something for everyone—from intriguing walled cities like Fez and Marrakesh to mountain hiking adventures to luxury overnight “glamping” in the Sahara Desert. I recommend finding an organized tour to help navigate the long distances between destinations as well as access to sights off-the-beaten path, including many of the synagogues and cemeteries. Consult the Moroccan National Tourist Office for both general and Jewish visiting information.

Here are just some of the top Jewish destinations:

CASABLANCA

The city made famous by Hollywood may be less romantic and enticing than the movie suggests, but it still boasts the largest remnant of Moroccan Jewish life.

Top of any itinerary here must be the Museum of Moroccan Judaism. The carefully crafted exhibits display synagogue replicas, colorful traditional costumes and Jewish artifacts used at home and communally. One room showcases framed photos of the extensive restoration project underway for Moroccan synagogues and cemeteries.

Beth-El synagogue is the largest and most public of the 16 synagogues still operating in the city (out of more than 30 that once existed). Enter through a large garden courtyard and up a curved staircase to find a grand but typical Sephardic layout with a wooden bimah in the center, bright stained-glass windows and carved ceilings in the Arabic style. A tiny kosher bakery sells challah and local pastry around the corner from the entrance.

TANGIER

This lively port city has long drawn writers and artists from America and Europe, including Henri Matisse, who called it a painter’s paradise. The Beit Hahayim cemetery sits right in the middle of the medina, just steps from a smelly but authentic fish market, and is bordered by houses where white sheets and undershirts hang from clotheslines. The cemetery features several examples of the elaborate tombstones found throughout the country.

A few blocks away are Shaar Raphael, the only synagogue that still holds regular services in the city, and Rue Synagogue, a short alleyway boasting a number of places of worship that have been restored to their former glory with tiled floors, decorative hanging lamps and mosaics throughout. A must-see is the Moshe Nahon synagogue, which some deem one of the most beautifully restored Jewish sights in the country.

A drive outside the city brings you past palaces and posh villas to a spot where the Atlantic Ocean meets the Mediterranean Sea;on a clear day you can see the Rock of Gibraltar.

The Tangier American Legation museum, the only overseas sight designated a national historic landmark by the United States Park Service, pays tribute to relations between the United States and Morocco, which in 1777 was the first country in the world to recognize American independence. The display cases are filled with newspaper clippings, maps and artifacts, including some Jewish tidbits. A special exhibit, “Customs and Costumes of Sephardic Morocco,” showcases a delightful collection of traditional Moroccan Jewish wedding gowns.

FEZ

Morocco’s first official mellah, or Jewish quarter, was established in Fez in 1438 in the shadow of the sultan’s palace. Two synagogues, the Ibn Danan and Slat Al Fassiyine, are further examples of exquisitely restored synagogues. Each sports a green-and-white tile floor with mosaics that border the Ark. In the newer part of the city, Roben Bensadoun synagogue welcomes visitors to fill its pews on Shabbat.

MARRAKESH

This “Red City” at the foot of the Atlas Mountains, named for the ubiquitous salmon-hued buildings, accosts the senses at every turn. Mule-drawn carts compete with motorbikes and pedestrians along the narrow alleyways of the medina’s massive souks, while jugglers, snake charmers and musicians vie for attention.

In the mellah, the Slat Al Azama synagogue boasts a tranquil courtyard, replete with a traditional mosaic fountain. In addition to an ornate sanctuary, the building includes several side rooms with photos, maps and explanations of the history of the community. Visitors will find additional local history at the Miara cemetery, also located in the mellah. (For more information on Jewish life in the city, go to jmarrakech.org.)

The Museum of Moroccan Culinary Art, inaugurated in November 2019, is housed in an elegant former palace and includes a whole room devoted to Moroccan Jewish cuisine. Cooking lessons are available.

Jardin Majorelle, a garden once owned by Yves Saint Laurent and his partner, provides a serene and accessible oasis in a chic section of the new city. The grounds contain the Berber Museum, which includes artifacts like a mezuzah case and ner tamid, illustrating the fascinating connection between Jews and the indigenous population of Morocco.

CHEFCHAOUEN

Legend has it that it was Jewish influence that first transformed this mountain town between Tangier and Fez into the “Blue City,” bringing a practice from Spain of painting houses blue to remind the Jews of God and heaven. The tradition continued long after the Jews left, and now this enchanting city with winding, cobblestoned streets filled with craft shops has become a popular tourist destination.

Lisa Hostein, Hadassah Magazine’s executive editor, visited Morocco in November 2019 as a guest of the Moroccan National Tourist Office.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

S P Fischer says

I just returned from my 1st visit to Morocco. It was amazing to feel so welcomed by our Berber guides and see Jewish history preserved by the king’s government! Here’s my favorite anecdote, not mentioned in this very informative article:

During World War 2, while the Nazis were spreading into North Africa, Hitler contacted then King Hassan 2 to ask how many Jews lived in Morocco. The king replied, None. Here we are all Moroccans.

Elaine Finkelstein says

As someone who has researched Jewish communities throughout North Africa, I want to emphasize just how unique Morocco’s commitment to preserving Jewish landmarks truly is. Alongside the restoration of over 160 Jewish cemeteries, there are ongoing projects to digitize historical documents—like ketubot (marriage contracts) and communal records—which offer invaluable insights into everyday Jewish life in places like Casablanca, Fez and Marrakesh.

Another fascinating aspect is the continued tradition of Hiloula pilgrimages, where Moroccan Jews from Israel, France, and beyond return annually to pay homage to revered rabbis. These efforts not only safeguard the physical heritage but also help keep family narratives and cultural practices alive across generations. It’s a testament to how deeply woven the Jewish legacy is into Morocco’s broader identity.