American View

Feature

Jewish Suffragists, White Dresses and Yellow Roses

Some things never go out of style. Take the white suit: It looked as fresh at recent State of the Union addresses, sported by a wall of congresswomen, as it did 100 years ago when a coalition of Jewish, Protestant, Catholic and African-American suffragists donned the pristine hue to wage war against sexism—and win the vote for women in August 1920 with the 19th Amendment to the Constitution.

From the Woodrow Wilson-era yellow rose—the suffragists’ symbol in Tennessee, the final state to ratify the amendment—to the Trump-era pink pussy hat, branding has accompanied activism in women’s fight for political representation. Indeed, those yellow roses have sprouted again at the Suff Shop, which sells everything from brooches to coasters in a nod to the merchandise—slogan-bearing pencils, messenger bags, dishware and other household items emblazoned with supportive sayings—that suffragists handed out as fundraising incentives a century ago.

And as America celebrates the centennial of female suffrage this year, what’s striking is how much today’s female leaders have in common with our activist foremothers, many of whom were Jewish. A century before Twitter, theirs was a story replete with petty rivalries, political marriages of convenience, eye-catching antics and tabloid-friendly arrests at demonstrations that wouldn’t be out of place in 2020 America.

Perhaps the best example is Anita Pollitzer, a granddaughter of a Prague rabbi who went from teaching Hebrew school in Charleston, S.C., in the early 20th century to working alongside Alice Paul, a notorious anti-Semite who headed the influential National Woman’s Party. As a white-clad member of the Silent Sentinels, the in-your-face NWP protest group, Pollitzer pestered Wilson’s White House until she was dragged off by the police. (Pollitzer’s other claim to fame is championing the artwork of her Columbia University Teachers College classmate, Georgia O’Keefe.)

Or consider Ernestine Rose, a 19th-century rabbi’s daughter from Poland who reinvented herself as an American atheist, freethinker and colleague of leading social reformer Susan B. Anthony. Rose, who described herself as “a feminist from the age of five,” lectured on abolitionism before becoming president of the National Women’s Rights Convention in the 1850s.

“Rose was a real anomaly; there were so few non-White-Anglo-Saxon-Protestant women in the movement then,” says Pamela Nadell, who directs the Jewish Studies Program at American University and whose latest book is America’s Jewish Women: A History from Colonial Times to Today. But from its beginnings at the upstate New York Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, “there’s an incredible complexity to the women’s movement and to women’s activism,” Nadell adds, “as the elites in America are challenged by the dramatic transformations in American society.”

HADASSAH MAGAZINE ONLINE DISCUSSION GROUP PRESENTS

Votes for Women: An Event Exploring Jews and Suffrage

Join Hadassah Magazine Executive Editor Lisa Hostein on July 22 at 7:30 p.m. EDT for a live online discussion about the contribution of Jewish women to the suffrage movement, and what that legacy means today. The Zoom event will feature leading American Jewish historians Pamela Nadell, Melissa Klapper and Judith Rosenbaum. Please register here.

From New York City’s Lower East Side to the San Francisco Bay Area, waves of immigration in the early 20th century were changing America’s ethnic complexion. World War I sent thousands of Americans overseas and created a new order in Europe and the Middle East; the Ottoman Empire dissolved, Zionism flowered and the League of Nations emerged. Marxists everywhere cheered Russia’s Bolshevik Revolution. These developments brought people and ideas from around the world into contact with each other, creating the ferment for social change.

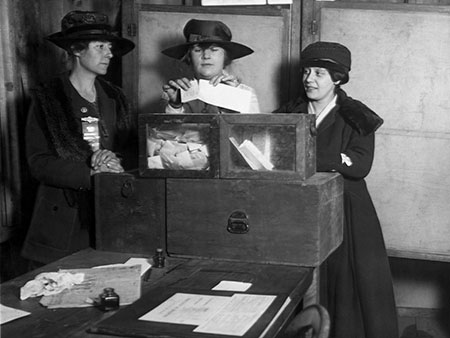

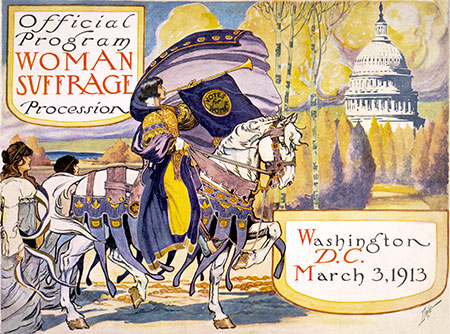

Against this backdrop, Jewish women were key mobilizers for suffrage. Activists, often dressed in white, shouted from soapboxes, organized marches (including a 1913 staged procession in front of the White House featuring floats and horses), wrote letters to editors and politicians, even went on hunger strikes that resulted in being force-fed by police. By grabbing headlines with these stunts, suffragists hoped to extend to all American women a right that some had enjoyed in limited instances since the 1830s, when parts of Kentucky were the first in the nation to allow female taxpayers—widowed property owners, for instance—to vote in school elections.

By 1918, President Wilson was persuaded to support a proposed 19th Amendment to the Constitution, and by May 1919, the House of Representatives voted in favor. The Senate followed, and the amendment’s success was sealed when Tennessee ratified the measure in August 1920. It was the 36th state to do so, fulfilling the requirement that three-fourths of the then-48 states vote in favor of ratifying the amendment.

It had been the gradual, state-by-state expansion of voting rights prior to 1918 that had built support among members of Congress for the national amendment. Western states such as Washington and California were the first to enact statewide suffrage, beginning in 1910.

“These were newer places that had a little bit more of a frontier mentality, so they were less wedded to tradition,” explains Judith Rosenbaum, a historian who heads the Jewish Women’s Archive.

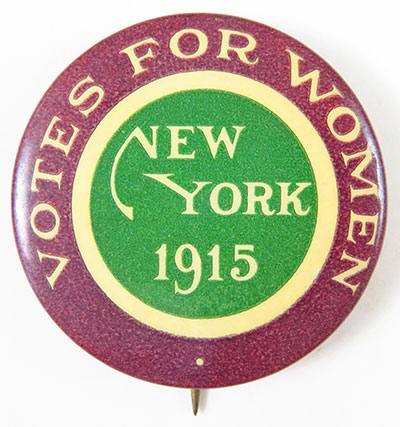

But it was New York—then the largest state, and always the East Coast bellwether—that lent momentum for a nationwide push. New York’s successful 1917 statewide referendum, after several failed attempts, revealed the power of an increasingly multicultural America. African-American, Irish, Italian and Jewish men were critical blocs who gave their wives, mothers and sisters the right to vote. More than three-quarters of Manhattanites were then foreign born, and the urban vote clinched victory for the state overall.

“Even though the movement was definitely white, middle-class Protestant women—that’s who the leadership was, and who they envisioned as the ideal voter—those same women recognized that they needed to enroll these other groups in the cause,” says Melissa Klapper, a professor of history and Jewish studies at Rowan University and the author of Ballots, Babies, and Banners of Peace: American Jewish Women’s Activism, 1890-1940. “But there was always a lot of tension.”

Jewish women like Pollitzer and Rose may have been idealists, but they were also pragmatists who cut deals with anti-Semites in order to achieve collective goals—much as progressive Jewish women have turned out in pink pussy hats for the Women’s March in recent years, despite anti-Jewish rhetoric from some of the national march’s founding organizers.

A century ago, that rhetoric ranged from garden-variety snobbery and blaming Jewish voters for defeated referenda to complex theological arguments that essentially “took down religion as being patriarchal, and blamed it all on the Jews,” as Klapper says, referring in particular to The Woman’s Bible, a notorious title by influential suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton. That anti-religious stance is “why she’s not on the dollar, and Susan B. Anthony is,” Klapper notes of the karma, divine or not, that has tarnished Cady Stanton’s legacy.

It was one thing for individual Jewish women to make common cause with anti-Semites, however, and another for Jewish organizations to lend formal support.

“The National Council for Jewish Women was crawling with suffragists,” says Klapper, “but the organization never endorsed suffrage.” There were constant reminders that Jews were seen “as not truly American, not good enough. So collectively, there was this feeling that, ‘Well, they don’t want us.’ ”

Likewise, Hadassah declined involvement in the cause. The exception was a 1918 telegram from the organization to Wilson, urging him to support the women’s vote. Hadassah was focused more on issues in then-Palestine, where Zionist women looked to American suffragists as inspiration for an egalitarian state.

Still, many Hadassah women were devoted to the vote. They included Rachel Szold Jastrow, sister of Hadassah founder Henrietta Szold—they and their six sisters were rabbi’s daughters, too—who represented the Wisconsin Woman Suffrage Association at the State Legislature. Rose Jacobs and Irma Lindheim, two early Hadassah presidents, advocated for suffrage in between trips to Palestine.

“Jewish women helped to bridge the class divide,” says Rosenbaum. “They helped working-class women understand why it was worth their while to work with upper-class women to get the vote, and upper-class women to understand why having the vote would be an important tool to protect women of all classes.”

In some families, suffrage united the generations, a phenomenon echoed at rallies today, when mothers and daughters march in solidarity around issues like anti-Semitism, reproductive rights or racial justice. In the frontier West, Hannah Marks Solomons—whose family founded San Francisco’s Congregation Emanu-El—lobbied for women’s rights alongside her daughter, Selina Solomons, who did her mother proud as a key player in California’s 1911 referendum. (Another daughter, Adele, became a doctor, unusual for women of the time.)

“The Solomons’ story speaks to how the movement appeals to various generations, and also to just how long the movement was,” observes Rosenbaum.

It also speaks to how in some circles, suffrage was the lightning-rod women’s issue of its time, much like abortion is today.

“You see these stunning divides even within families,” says Nadell. “My favorite characters were Maud Nathan and Annie Nathan Meyer, the founder of Barnard College, two sisters of the elite Nathan family.” How elite? Maud Nathan was a card-carrying member of the Daughters of the American Revolution, tracing their ancestry to the Colonial era. Their cousins included “New Colossus” poet Emma Lazarus and Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo.

“And they hated each other,” Klapper says of the Nathan sisters. “One was for suffrage and the other was like, ‘Not me!’ ” The activist Maud Nathan lobbied Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Wilson and led rallies on behalf of the women’s vote, while Meyer countered what

she called Nathan’s “utterly abhorrent” and “noisy” efforts with anti-suffrage speeches at Barnard. Like many elites, Meyer was skeptical about extending the vote to working-class immigrant women.

“But then, as soon as she got the right, she became involved with the League of Women Voters,” notes Klapper.

As the euphoria of victory subsided, progress was fitful for women who dreamed of political equity. Voter turnout on Election Day One—November 2, 1920—was a disappointment, says Klapper, and has never been “as high as suffragists had hoped.” Yet in every presidential election since 1980, more women have turned out to vote than men, according to data collected from the United States Census Bureau. In 2016, 63.3 percent of eligible women cast a vote, compared to 59.3 percent of men.

Beyond showing up at the polls, you might have expected newly enfranchised women to start running for office. But politically charged women were more likely to fight for the Equal Rights Amendment, a constitutional guarantee of equal legal rights for Americans regardless of gender, first proposed by suffragist Alice Paul in 1923 and still in limbo.

Jewish female activists turned their energies toward other causes: workers’ and civil rights, nuclear disarmament, the peace movement of the 1960s, Zionism.

Indeed, it was many years before suffragist ambition translated into real political clout, despite some early outliers, one of whom—Republican Jeanette Rankin of Montana—was elected by male voters in 1916 to Congress years before ratification of the 19th Amendment. In 1925, Florence Prag Kahn, a Republican from California, became the first Jewish congresswoman in 1925.

Once again, America is experiencing enormous change in the realm of women in politics. After years of stagnation, the number of women both running for and holding office is growing fast. A hundred years after the Solomons’ and Jastrows toasted their hard-won victory—though not with champagne, as Prohibition began the same year—Congress now counts 127 women, split between 26 senators (two of whom are Jewish, Democrats Jacky Rosen of Nevada and Dianne Feinstein of California) and 101 representatives.

In 2018, the election of newcomers Elaine Luria of Virginia, Kim Schrier of Washington, Elissa Slotkin of Michigan and Susan Wild of Pennsylvania, all Democrats, brought the number of Jewish women in the House of Representatives to nine. Like the Silent Sentinels a century earlier, female and Jewish newcomers are enthusing some and unnerving others with positions and alliances considered radical in some quarters.

“There’s certainly a continuity of Jewish women’s activism,” reflects Judith Rosenbaum. At the 100 year mark, she offers her own birthday wish for the suffrage movement: “That we learn from the successes of women in the past and draw on what history has to teach us.”

After all, certain trends—like power, equality and wearing white—never go out of style.

MARKING 100 YEARS

The Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission offers a wealth of historical information, a calendar of centennial events and a virtual, curator-led gallery tour of “Rightfully Hers: Women and the Vote” at the National Archives Museum in Washington, D.C. Be sure to check out all the kids’ activities, including printable Susan B. Anthony paper dolls, a suffrage reading list and more.

The 2020 Women’s Vote Centennial Initiative counts among its partners the Jewish Women’s Archive and the National Museum of American Jewish History. You’ll find upcoming programs, reading lists and test-your-knowledge quizzes for all ages, classroom resources (including an archive of primary source documents) and souvenir merchandise.

The Suff Shop is an online emporium for suffragist swag: shirts and magnets featuring the yellow rose, feminist-slogan drinkware and ornaments, even framed replicas of the 19th Amendment.

PBS celebrates the centennial with a documentary film, “The Vote,” and a collection of suffrage-related films.

Hilary Danailova writes about travel, culture, politics and lifestyle for numerous publications.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Gary Ferdman says

Hilary Danailova’s timely article about Jewish suffragists suffers from one major flaw. Like many other writers and scholars, she feels compelled to disparage two extraordinary women, leaders of one of the great social movements in our nation’s history, without presenting sufficient evidence to support her allegations of their Anti-Semitism.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s calling out of biblical Judaism for being patriarchal in her The Woman’s Bible hardly qualifies her as an anti-Semite. Her major focus is on the sexism of Christian religions which drew upon the Old Testament. She is squarely in the camp of her Suffragist colleague Ernestine Rose, the Rabbi’s daughter whose questioning of traditional Judaism’s attitudes toward women led her to atheism suffrage and abolition; feminist intellectuals like Letty Cottin Pogrebin; and the 1960’s -70’s Jewish feminists whose rejection of biblical and traditional Jewish patriarchy, beginning with Adam and Eve, led them to resurrect and embrace the feisty, feminist Lilith.

Danailova describes Alice Paul as a “known” and “notorious” Anti-Semite without presenting any evidence. On the contrary, she mentions that Paul hired Anita Pollitzer as a key National Woman’s Party organizer. Paul and her Party welcomed many other Jewish leaders, several of whom joined Paul in picketing Woodrow Wilson’s White House and were arrested. A search of Paul’s biographical material turns up one reference. In a 1975 interview, National Woman’s Party leader Mabel Vernon commented about Paul’s relationship with party member Rebecca Reyher that: “She’s Jewish, and have you detected Alice’s antagonism for Jews, darling?” Hardly enough to justify alleging that a woman who started her career helping Jewish immigrants and later helped rescue Jews from the Nazis is a “Notorious Anti-Semite.”

Rather than being subjected to unfounded accusations of anti-Semitism, Woman Suffrage leaders like Stanton and Paul should be celebrated for the extent to which they overcame the rampant Anti-semitism and racism of their times to help open the door for voting rights for all women.

Judith Mayer says

Thank you Hilary Danailova for this generally enlightening article.

I also wonder about the basis for calling Alice Paul a notorious anti-semite. I’ve worked extensively with suffrage archives, including Alice Paul’s and NWP correspondence, and have found little to justify that description, beyond the pervasive class and ethnic biases of those times. Along with much of the rest of the suffrage movement, as you point out, suffragists across the spectrum made many expedient (though nasty in retrospect) decisions to prioritize suffrage over any other goal, or struggles for rights or recognition. I’d appreciate it if Hilary Danailova could respond and explain.

Ruth Radetsky says

Alice Paul took my German Jewish refugee family into her home/office in Geneva in (I think) 1939 or 1940, and made them welcome and valued members of her community. She was instrumental in one Jewish family’s surviving with some dignity. My grandmother always spoke of her with love and gratitude.

You should not make the assertion that Paul was a “notorious anti-semite” without evidence.