Israeli Scene

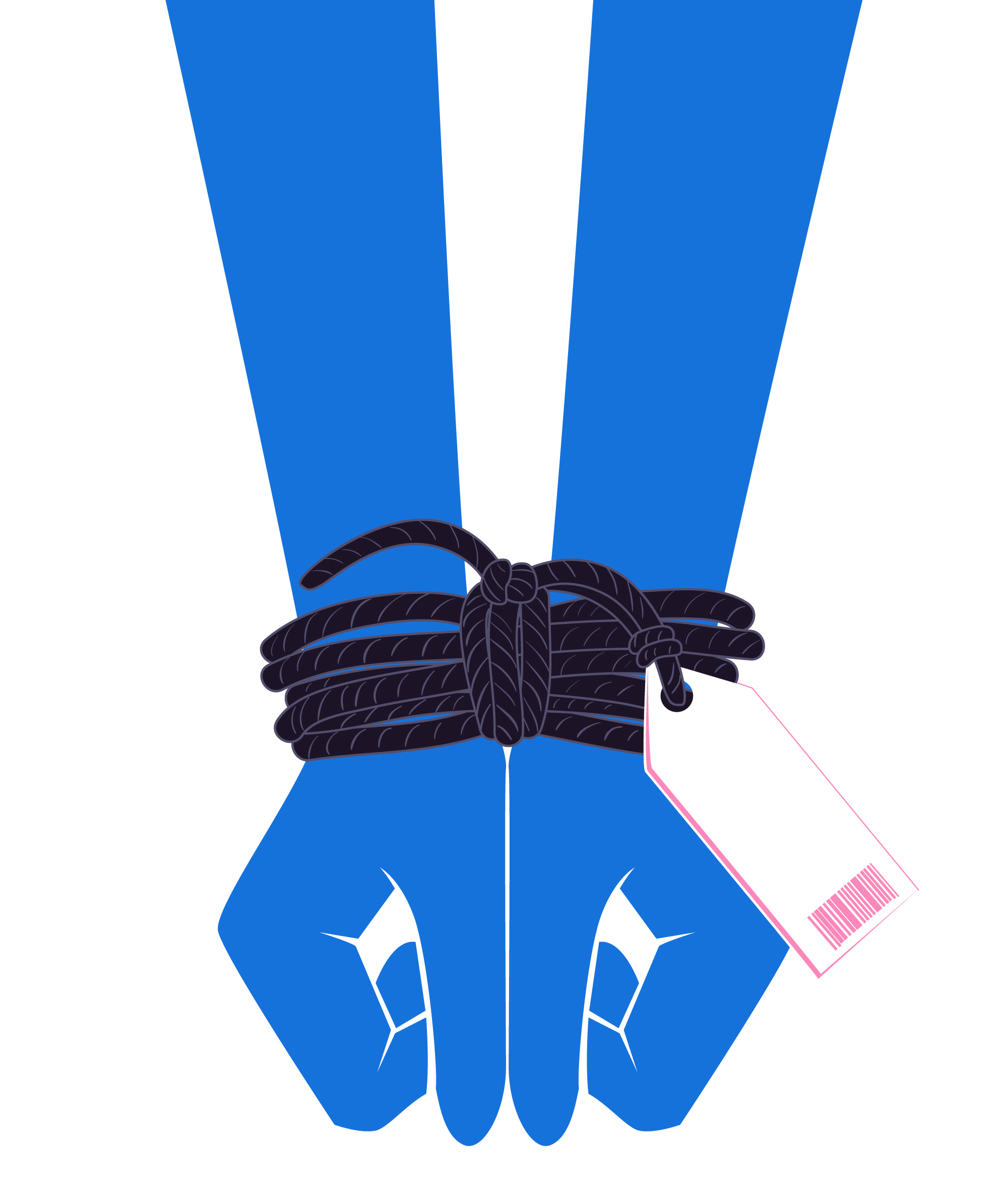

Turning Around the Record on Sex Trafficking in Israel

In 2003, attorney and social activist Nomi Levenkron was sitting in a Tel Aviv courtroom, begging a municipal judge to grant temporary working visas to two women from Moldova who had been trafficked to Israel and forced to work as prostitutes in a brothel. One of the women had given birth prematurely after being kicked in the stomach by her pimp.

In 2003, attorney and social activist Nomi Levenkron was sitting in a Tel Aviv courtroom, begging a municipal judge to grant temporary working visas to two women from Moldova who had been trafficked to Israel and forced to work as prostitutes in a brothel. One of the women had given birth prematurely after being kicked in the stomach by her pimp.

Levenkron, then the legal adviser to the Hotline for Refugees and Migrants, a group that advocates for victims of sex trafficking and migrant laborers, had filed suits on behalf of the women—a criminal case against the traffickers and a civil suit demanding money from them to compensate the women for their work. Levenkron was seeking the temporary working visas so the women couldn’t be deported while they testified against the traffickers.

Many in the law enforcement community had little sympathy for such women at the time, says Levenkron, who now teaches at the Institute of Criminology at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. She recalls a policeman telling her that since “they are staying illegally” they should be summarily deported.

“During the trial, one of the women committed suicide, at age 21,” she says, describing her as “one of my favorites. She was sweet and amazing and helped with other women, calling me when they arrived at a safe house.” Levenkron still feels the pain of that loss: “It was the worst case of my life.”

That was back when Israel had only begun addressing its sex trafficking crisis. In 2001, the country had been listed as a Tier 3 nation by the United States—the lowest ranking in the State Department’s annual Trafficking in Persons Report. Today, through the efforts of nonprofits and lawmakers in the Knesset, victims of sex trafficking in Israel receive a work visa and rehabilitation in a shelter for a year as well as medical care and state-funded legal aid. In 2012, the country rose to Tier 1 in the State Department report, and Israel is now considered one of the top global reformers in the war against sex trafficking, even as anti-trafficking advocates believe there is more work to be done.

Israel’s location as a bridge between Europe and Asia, its original lack of anti-trafficking laws and the ongoing waves of immigrants from all over the world initially set the stage for the trafficking crisis. But it was the massive influx of Russian-speaking immigrants arriving just before and after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 that exacerbated the problem.

During the late 20th through early 21st centuries, over a million Jews from former Soviet republics landed at Ben-Gurion Airport. At the same time, a far less welcome ingathering was taking place: Sex traffickers were smuggling in Russian, Ukrainian and Moldovan women, mostly non-Jews, circulating them as prostitutes among the brothels of Tel Aviv and Israel’s other major cities. A Knesset inquiry found that between 2001 and 2005, 3,000 to 5,000 women were smuggled into Israel each year and forced into prostitution, with the industry bringing in more than a billion dollars annually.

Lured to Israel by the promise of work, the women, most between the ages of 16 and 45, were either fleeing abuse at home or the turmoil left by the breakup of the Soviet Union. Their traffickers claimed they would earn money once they paid off the cost of their transport. Instead, “there was systematic rape of the women, many of whom were not allowed to leave the premises and were held and their passports confiscated,” says Rachel Gershuni, a former coordinator of the National Anti-Human Trafficking department of the Ministry of Justice.

Levenkron, the attorney, recalls sitting with victims in prison all day “hearing stories, eating prison food and trying to figure out what to do.”

That situation shifted dramatically after the 2001 United States report, when Israel was placed alongside third-world countries such as Pakistan and Bahrain in its unwillingness to combat sex trafficking. The report noted that victims of trafficking were often “detained, jailed in a special women’s prison separate from other female prisoners and deported.” If the situation had continued, Israel risked losing its non-humanitarian aid from the United States.

Responding to the pressure, Israel passed a series of laws to aid victims. In 2006, the government of Prime Minister Ehud Olmert passed the Anti-Trafficking Law, which criminalizes “abduction for the purpose of slavery or forced labor and conveying a person beyond the boundaries of a state.” It also makes illegal “causing a person to leave a state for the purposes of prostitution or slavery.”

Read Rahel Musleah’s report on how Jewish organizations as well as a number of Jewish women are combating sex trafficking in the United States through advocacy, information and education in The Jewish Response to Modern-Day Slavery.

While the law does not define sex trafficking as only transnational, most court cases have focused on foreign women brought in to work as prostitutes. The boundaries between sex trafficking and prostitution can be hard to define. According to a 2016 report from the Ministry of Labor, Social Affairs and Social Services, Israel is home to around 12,000 sex workers. More than three quarters want to leave sex work, according to the report. Prostitution is legal in Israel, though organized prostitution—i.e., brothels and pimping—is prohibited. A new law set to take effect in May will criminalize the procurement of sex services—a move that has been lauded by Israeli human rights organizations.

Nonprofits such as the Hotline for Refugees and Migrants, Turning the Tables and Isha L’Isha have long advocated against trafficking and prostitution. These three groups—all former grantees of the Hadassah Foundation, which supports social change by funding organizations focused on women and girls—also provide public education and support for the victims.

Israel’s legislative push against trafficking was part of a fundamental change in culture in the late 20th century that included a growing focus on feminism and issues that affect women, according to Merav Michaeli, a journalist-turned-Knesset member. This shift happened during the 1960s and ’70s in the United States, she says, when Israel was grappling with existential threats. It wasn’t until the 1990s—“the first decade in which we did not have a major war”—that such sentiments began to shake up Israeli society, says the Labor Party MK.

“By 2001, we had built a public awareness” around prostitution and trafficking, she says, a cultural shift that enabled the police to take action. “It’s nice to have legislation but it’s dead words unless the police really put some effort into it.” Between legislative changes, dedication to enforcement and public education, the estimated number of new sex trafficking victims in recent years has declined to about several hundred annually, according to government estimates.

Israel, in fact, is now advising some American groups on trafficking issues. In 2018, a group of law enforcement officials from San Francisco traveled to Israel to talk to their counterparts about leveraging local nonprofits to cooperate with police. And in January, in honor of National Slavery and Human Trafficking Prevention Month, Dina Dominitz, Israel’s current National Anti-Human Trafficking coordinator, and Matan Zamir, Israel’s deputy consul general in San Francisco, were invited by the San Francisco Collaborative Against Human Trafficking to an online forum to answer questions in light of the increase in sex trafficking in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Israel’s approach to trafficking is not without controversy. In 2018, the United States State Department’s Trafficking in Persons Report upheld Israel’s Tier 1 status but faulted the country for not codifying “the use of force, fraud, or coercion as an essential element of the crime,” criteria used in the United States as well as a number of other countries.

“But Israel’s law has advantages,” contends Gershuni, the former anti-trafficking coordinator for the government who played a key role in drafting the 2006 law. She acknowledges that “it’s easier to extradite and learn from other countries’ judgments when you have more of a common language.” But, at the same time, defining trafficking as any “transaction in a person” makes it much easier to enforce, since no proof of coercion or threat is required for conviction.

It can still be very difficult for women to admit to being exploited or trafficked, notes Dr. Dvora Bauman, director of the Hadassah Medical Organization’s Bat Ami Center for Victims of Sexual Abuse, a multidisciplinary treatment center in Jerusalem. She recalls being certain that a 20-something woman who came to Bat Ami in 2017 had been trafficked and forced into prostitution. The woman claimed she had been attacked and raped by a stranger. She “had a look of fear in her eyes,” says Dr. Bauman. The fact that she spoke Russian but little Hebrew, despite having been in the country for several years, was one sign that she had been trafficked.

After several hours, however, the woman, who needed treatment for a sexually transmitted disease she contracted from a client, disclosed that she had come to Israel on the pretense of having a contract to work with a family. But once she arrived in the country, “she became a sex slave,” Dr. Bauman says. Only after she acknowledged she had been trafficked were the Bat Ami staff able to bring in the police.

Dr. Bauman believes that the level of trafficking in Israel has diminished significantly in recent years, but her experience with women like this suggests it’s still more prevalent than the official numbers suggest.

Indeed, despite the generally improved situation, advocates worry that the trend is shifting backward. “There was a big change for the better but now, over the last two years, it’s starting to appear again in different ways and forms,” explains Lilach Tzur Ben-Moshe, executive director of Turning the Tables, a Tel Aviv-based nonprofit that assists women trying to leave prostitution. The organization offers economic support and vocational training to these women.

The uptick may be due to new strategies adopted by traffickers. According to Ben-Moshe, criminals are bringing women from Ukraine, Moldova, Russia and Georgia on three-month tourist visas to work as prostitutes. These women are harder to track because they leave Israel once their visas are up, though some may return for another three-month stint at a later date.

“This is a very new way of trafficking,” Ben-Moshe says. Around 100 such women are “identified every year, indicating that there must be many more” who are not discovered.

Another unresolved problem is internal trafficking. “Even if you are bringing teenagers from Beersheba to Tel Aviv to work,” Ben-Moshe insists, “it’s also trafficking.”

“Israel is doing O.K. on dealing with trafficking,” preventing the smuggling of women into the country, but it is “less O.K. on dealing with prostitution, but it’s improving,” says Michaeli, the lawmaker. “It’s our job—me, my colleagues and civil society organizations—to make sure that it does not go down too low in the priorities” of law enforcement and legislators as well as those who are helping rehabilitate the victims.

Sam Sokol is a Jerusalem-based correspondent and the author of Putin’s Hybrid War and the Jew: Antisemitism, Propaganda, and the Displacement of Ukrainian Jewry.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Kenzy Turner says

Good to hear that it’s reducing, but it supposed to stop completely.

Hope it will get resolved soon.