The Jewish Traveler

Feature

Vintage Israel: Touring the Land With Wineglass in Hand

Michael Greenwald, a retired Philadelphia attorney, remembers squeezing his first trip to Israel, in 1962, into little more than a day. When he returned in 2019 for an intensive 10-day tour, he set aside a day solely for visiting Tzora Vineyards, a boutique winery near Jerusalem.

Michael Greenwald, a retired Philadelphia attorney, remembers squeezing his first trip to Israel, in 1962, into little more than a day. When he returned in 2019 for an intensive 10-day tour, he set aside a day solely for visiting Tzora Vineyards, a boutique winery near Jerusalem.

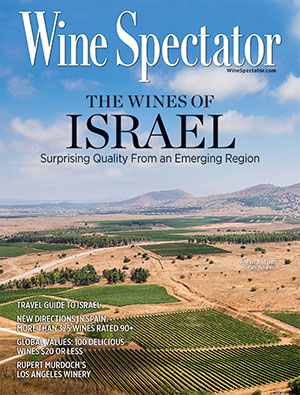

“I had read about this winery in Wine Spectator a few years ago, and I knew I had to taste its wines,” said Greenwald, a devoted oenophile. The magazine’s October 2016 issue, with a cover story on Israel, had ranked Tzora’s wines as 90 or higher, out of 100.

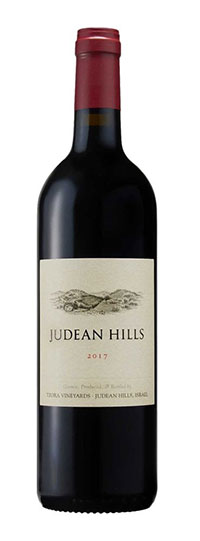

Greenwald was not disappointed. After hearing a detailed presentation and sampling Tzora’s offerings, he came away with two bottles of Judean Hills red, a full-bodied blend with an aroma of fresh blackberries and ground black pepper.

Tzora’s success is part of a wider trend that is shaking up the tourism industry. As Israel’s wine producers have dramatically multiplied since the 1980s and the quality of their varietals and blends has soared, tastings and vineyard tours have become an increasingly popular way to experience six distinct wine regions: the Golan Heights, Galilee, Samaria, Judean Hills, Judean foothills and the Negev.

As of 2018, Israelis, including some in the Golan Heights and the West Bank, operated four large wineries (each producing more than five million bottles per year); 12 medium-size ones (more than one million bottles); and over 250 boutique wineries (up to 100,000 bottles). Many offer a tasting experience.

“We’ve seen steady growth,” said Alon Yitzhaki, a licensed tour guide and sommelier who co-founded Israel Wine Tour 10 years ago. “The world is gradually learning about the quality of Israeli wine.”

Yitzhaki, 44, gives 15 to 25 evening, single-day or overnight wine tours a month, opting for boutique wineries over larger establishments.

A favorite stop on many of his tours is Agur Winery, in the Judean foothills. Founder and winemaker Shuki Yashuv has post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from his service during the Yom Kippur War, speaks seven languages, is a carpenter and a philosopher and “has been making kosher wine for 20 years,” said Yitzhaki, noting that Yashuv is a complete atheist. At Agur, visitors sample Yashuv’s various blends either indoors, surrounded by floor-to-ceiling racks of whites and reds as well as repurposed wooden barrels, or alfresco, sitting at picnic tables amid simple, scenic landscaping.

Wine and winemaking have deep roots in Jewish tradition. The biblical record goes back to Noah, whose vineyard is the first mentioned. In Deuteronomy, vines are among the blessings promised the children of Israel if they obey God’s commandments. Wine figured prominently as a Temple offering and in ceremonial practice as well. Ancient wine presses have been uncovered in archaeological digs throughout Israel, testimony to a flourishing wine industry that continued for centuries.

But winemaking had shrunk to a small scale by the 19th century, when philanthropist Sir Moses Montefiore urged its revival. Baron Edmond de Rothschild—owner of the Château Lafite Winery in Bordeaux—brought in European grape varieties and experts. He went on to finance wineries in two pioneering settlements, Rishon LeZion (founded in 1882) and Zichron Ya’akov (1890). These two wineries, under the Carmel label, were the dominant players in Israel until the 1980s and remain among the country’s leading producers.

Israel’s 20th-century wine renaissance began with the discovery in the 1970s that the recently captured Golan Heights had ideal conditions for growing grapes. In 1983, the Golan Winery was established and started producing good quality dry red wine, “which was not known in Israel” before then, according to Eran Pick, the country’s only Master of Wine (a coveted title bestowed by the British Institute of Masters of Wine). Golan’s success spurred existing producers to improve.

Then, in the 1990s, a number of wannabe winemakers opened small-scale boutique operations, said Pick, who has been Tzora’s winemaker since 2006. At the same time, Israeli wine professionals were bringing back know-how from agricultural studies abroad; and the opening up of air travel, thanks in part to the abolition of Israel’s prohibitive travel tax, led to more Israelis going abroad and becoming knowledgeable about wine.

Tzora, founded in the Judean Hills in 1993, was among Israel’s earliest boutique wineries. Its founder, Ronnie James, introduced to Israel the importance of terroir—the various aspects of the vineyard, including the altitude, humidity, soil composition and flowers. These are especially important for Tzora, an estate winery, which means that it produces wine solely from its own grapes, grown in especially picturesque terraces that hug the steep, rocky slopes. Tzora also markets its wines together with three neighboring labels—Domaine du Castel, Flam and Sphera—as the Judean Hills Quartet, reviving a 2,000-year-old winemaking tradition in the area.

In 2002, Tzora became kosher in order to increase sales. There is a demand in Israel and in Jewish communities abroad for fine kosher wine, so carrying a hechsher enlarges the potential market. Consequently, the switch means that Pick, who is Jewish but not observant, is no longer allowed to touch or even pour the wine.

So what makes a wine kosher? From the time the grapes are crushed, the juice and ultimately the wine may be touched or poured only by religiously observant Jews. Mevushal wines are those that have undergone flash pasteurization and therefore may be poured (for example, at a catered event) by anyone.

According to Zahi Dotan, manager of the Israel Wine and Grape Board, 95 percent of the 40 million bottles of wine produced in Israel annually is kosher, as are all the large and mid-size wineries. Exported wines are almost exclusively kosher.

Tzora, however, wants to be known “as a winery that makes good wine that happens to be kosher,” said Pick. And the Wine Spectator rankings definitely helped, boosting visits to the winery, according to Pick. Among Tzora’s varietals are the Judean Hills red that Greenwald bought; Judean Hills white, a blend of chardonnay and sauvignon blanc grown on old terraces in shallow terra rosa, a red clay soil, with a subsoil of limestone; and a dessert wine for which the grapes are harvested in July and then frozen.

Tzora, however, wants to be known “as a winery that makes good wine that happens to be kosher,” said Pick. And the Wine Spectator rankings definitely helped, boosting visits to the winery, according to Pick. Among Tzora’s varietals are the Judean Hills red that Greenwald bought; Judean Hills white, a blend of chardonnay and sauvignon blanc grown on old terraces in shallow terra rosa, a red clay soil, with a subsoil of limestone; and a dessert wine for which the grapes are harvested in July and then frozen.

In the north of israel, Tulip Winery is located in Kfar Tikva, a pastoral hilltop community of adults with developmental and emotional disabilities. The Itzhaki family of nearby Tivon, which founded the kosher winery in 1964, wanted to produce quality wine but also to create a socially responsible business, said Sivan Netzer, director of Tulip’s visitor center. Eight community members are employed in the winery; the oldest is 71.

“Most visitors don’t know about the village” in advance, Netzer said, noting that while Tulip is open about it, they “don’t use it as a marketing tool.”

The winery stands on its own merits, having won, among other awards, a gold medal for its Syrah Reserve 2014 from the Syrah du Monde in France. According to Netzer, Tulip was the first in Israel to blend gewürztraminer and sauvignon blanc. And in 2016, their flagship wine, Black Tulip, a blend of four varietals with an aroma of crushed blackberries and black currants, was one of six wines declared best in the world by Robert Parker’s The Wine Advocate.

At the other end of the country, in the Negev Desert, lies the Nana Estate Winery. This mostly arid region that is home to onagers, ibex and camels might seem an inhospitable site for a vineyard, yet it provides excellent conditions: loess soil, which is well-suited to agriculture; the weather, hot by day and cool by night; and the altitude—2,600 feet above sea level.

“My family’s dream was to establish a winery in the desert,” founder Eran Raz, 51, recounted over a crisp chardonnay. In 2007, he obtained a plot of land and planted his first vines. But between the dream and its realization came a history lesson. Raz had failed to take into account the flash floods and the reason that ancient crops were planted on terraces, which level the land and retain water. After the first winter, he had to build new terraces.

But his troubles did not end there. It turned out that his plot of land was in the middle of a smuggling route, and the Bedouin smugglers wanted him to disappear. “I had to sleep in the vineyard,” he recalled.

The smugglers offered “protection,” but he refused. Eventually, his persistence, the influx of other farmers from the nearby town of Mitzpe Ramon and completion of the wall Israel built on the Egyptian border to prevent illegal entry resolved that problem.

Raz’s three children help out, but the summer harvest is done by youngsters from Mitzpe Ramon who are paid by the crate. Every February, he hires soldiers who have completed their compulsory military service and who get a bonus from the state for working in agriculture for at least six months.

By 2014, Raz was producing his first wine. In 2019, he produced 55,000 bottles—red, white and rosé—but he must hit 100,000 to turn a profit. Meanwhile, the number of wineries in the area is growing.

To reach Nana’s rustic one-room tasting center, visitors drive off the main road and through flat vineyards—rows of surprisingly verdant vegetation set off against the dusty brown of the surrounding desert. A grove of fruit trees encircles the simple structure. In addition to catering events, Raz is building accommodations for overnight visitors—one room at a time—until his vision of combining wine and tourism becomes a reality.

Esther Hecht is a journalist and travel writer based in Jerusalem.

THE POLITICS OF WINE PRODUCTION

Some of the wines marketed as originating in Israel are produced, wholly or in part, in the Golan Heights and the West Bank. Such marketing has stoked activists of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement. Most recently, in March 2019, an official statement from the movement called for tourists to “avoid…wine tasting in illegal settlements.”

But sometimes boycotts backfire. In March 2019, a Dutch woman tweeted to protest that wine from the Efrat Winery, in the Judean Hills, was being marketed in a Dutch-based chain as a product of Israel. “Efrat and Judean Hills are in occupied Palestinian land,” she tweeted, according to a Jewish Telegraphic Agency report.

She was wrong. The Efrat Winery, one of the country’s oldest, is within the Green Line. Her tweet sparked a strong pro-Israel response among both Jews and non-Jews, and Efrat’s red and white wines in the Dutch chain’s online store sold out within hours.

The labeling issue has reached the courts in several countries. In July 2019, Canada’s Federal Court ruled that wine from Israeli settlements had to be so labeled so as not to mislead consumers. And in November 2019, the European Court of Justice issued a similar ruling that applies to all European Union countries.

In Israel, according to Alon Yitzhaki, co-founder of Israel Wine Tour, some tourists say they will drink wine from the Golan Heights because that area is under Israeli law, but not wine from the West Bank.

EXPERIENCE THE BIG PLAYERS

Reserve wine-tastings and tours in advance.

Carmel Winery, 125 years old and one of Israel’s first modern wineries, offers several options, all of which include a tour of its Zichron Ya’akov facilities, a film and a wine-tasting experience.

Barkan Winery, near Kibbutz Hulda, west of Jerusalem, crafts individually tailored experiences, including a terroir workshop and a wine night with a choice of refreshments.

Golan Heights Winery, in Katzrin, operates half a dozen tours, one of which includes a personalized meal and another that includes a visit to a vineyard.

Dalton Winery, in the northern Galilee, produces one million bottles a year with grapes grown in varied combinations of soils, including limestone and rich, heavy basalt. The family-owned winery conducts daily tours.

Tabor Winery, in the Galilee, south of Haifa, was established in 1999 by four families with vineyard experience. In 2012, the winery embraced progressive environmental standards.

Tishbi, in Binyamina, south of Haifa, produces one million bottles of wine annually and distills prize-winning brandy. The family-owned business also creates gourmet chocolates and other fine foods, and operates two restaurants as well as a wine- and chocolate-tasting center.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Lauren Stern Kedem says

I do wish that this article would have mentioned the Hadassah / Meir Shfeyah Youth Village Winery which opened in 2005 and is run by a professional sommelier and our Hadassah Youth Aliyah students.