Being Jewish

Feature

Daf Yomi Is Women’s Work

At 7:30 a.m. each workday, Caroline Musin Berkowitz drops off her 6-year-old daughter, Shira, at the school bus stop and then parks in front of a friend’s apartment, waiting to carpool to their offices. During that half-hour, she studies Talmud.

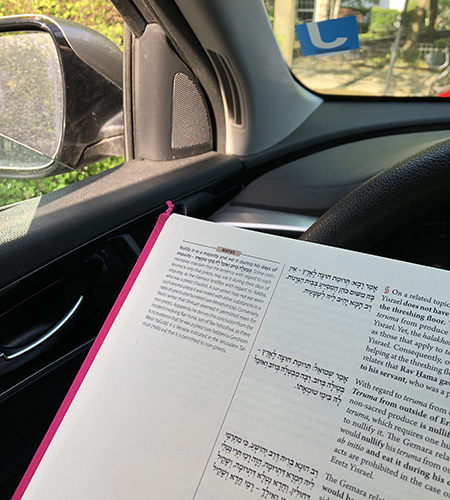

Musin Berkowitz, 41, a data administrator at The ARK, a Jewish social service agency in Chicago, opens the volume of Bechorot, the tractate that deals with laws about firstborn animals, blemishes and blood. She rests the book, protected by a stretchy hot-pink cover, on the steering wheel of her Kia Sorrento. It’s a rainy morning, so the wipers provide an accompanying rhythm as she moves back and forth between phrases in the original ancient Hebrew and Aramaic and the contemporary English translation, commentaries, footnotes and images in the Koren edition of the Talmud by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz.

For nearly two years, Musin Berkowitz has committed to a study practice called daf yomi, which in Hebrew means daily page. The cycle of learning engages thousands of men and a smaller number of women worldwide who aim to complete the 63 tractates, or 2,711 double-sided folios, of the Talmud over the course of seven and a half years, one daf—or folio—per day.

The Talmud, composed of the legal code called the Mishnah and the discussions of that code known as the Gemara, is the primary source of Jewish law, customs, folklore and ethics and has been the focus of Jewish study for generations. The text, which is traditionally laid out in the center of the page with layers of surrounding commentary, brings rabbis from different time periods into conversation as if they were speaking in a sort of stream-of-consciousness dialogue. Rabbi Meir Shapiro of Poland, who proposed the idea of daf yomi in 1923 to unify the Jewish learning world—then largely the province of men—could not have foreseen that almost a century later, women would join the cadre of learners. The current cycle will finish in January 2020, and there are siyumim, or concluding festivities, planned around the world.

While opportunities for women to study Jewish texts have been steadily increasing since the early 20th century, no statistics document the number of women claiming the Talmud as their own through daf yomi. But women committed to the learning cycle span the globe, in Toronto, London, New York, Jerusalem and elsewhere. Many are rabbis or educators, and they represent all denominations and ages. Some want to crack the mysterious code of Talmud, which was compiled over the course of the first several centuries after the start of the Common Era. Others were inspired to take part after the last cycle concluded in 2012 with a massive celebration at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, N.J. It was organized by the Orthodox umbrella organization Agudath Israel of America and drew 90,000 people, mostly men. Similar numbers are expected to flock to the same stadium on January 1 to celebrate the end of another cycle. A number of women have been inspired by the revolution in Jewish women’s learning and books like Ilana Kurshan’s best-selling memoir, If All the Seas Were Ink: A Memoir, which links daf yomi to events in her life. Female learners also have processed their daily daf through creative outlets—limericks, haikus and drawings—and social media has connected otherwise isolated learners.

“The Talmud is one of the crown jewels of the Jewish people,” Kurshan says in an email from Jerusalem, where she teaches Talmud and midrash at the Conservative Yeshiva, which is under the auspices of the Jewish Theological Seminary. “To cede the right or the ability to study Talmud to only half of the Jewish population is to deny ourselves access to a rich literary heritage that is rightfully ours.” Contrary to popular belief, “the Talmud is not a law code intended to tell Jews how to behave but a record of rabbinic legal conversations in which many questions are left open and unresolved. It is a text for those who are living the questions rather than those who have found the answers.”

Studying Talmud is also a “birthright experience” for Musin Berkowitz, a Hadassah life member who was raised in a traditional home in Des Moines, Iowa, and is now modern Orthodox. When she began learning, she was hesitant at first, she says, because of her lack of time and text skills. Reading Kurshan’s book as well as a friend’s encouraging Facebook post inspired her to take the plunge. Now, the pink-covered book is a constant presence in her life. “It gives me an intellectual outlet I don’t have in other parts of my life,” adds Musin Berkowitz, who shares her experiences on Instagram (@hashtagdafyomi).

Rabbi Robyn Fryer Bodzin, 45, one of the spiritual leaders at Beth Tzedec, a Conservative synagogue in Toronto, is Musin Berkowitz’s friend who had posted about Talmud on Facebook. Outside of her 11-year marriage, she says, learning daf yomi is the longest-running commitment she has ever made. “Why do it? Because I can,” says Fryer Bodzin, who was ordained in 2005 at American Jewish University’s Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies in Los Angeles. “Because the congregation sees their rabbi is always studying. Because it grounds me.”

Raised in the Conservative movement in Toronto, Fryer Bodzin began studying Talmud as a ninth-grader at TanenbaumCHAT, the Community Hebrew Academy of Toronto. Among her favorite phrases learned through daf yomi is “teiku,” which she uses in her personal life. “When there’s something the rabbis can’t figure out, they say ‘teiku,’ ” meaning the argument will remain unresolved until Elijah the prophet comes and explains it, at the time of the messiah. “Sometimes if you’re angry or have an argument with someone and can’t figure it out, stop and say ‘teiku.’ Stop and move on.”

Still, the study isn’t always satisfying, and can even be off-putting, she says. For the past year, the tractates have focused on animal sacrifices. “It’s so contrary to my life,” notes Fryer Bodzin, who is a vegan. The sections on animal sacrifices bother her more than those that include the ancient rabbis’ dismissive attitudes toward women. “The evolution of halacha and women’s place in it”—particularly in the liberal denominations—“makes those sections easier to read. That was then, this is now.”

For Kurshan, daf yomi became a comforting routine in the aftermath of a painful divorce. Now remarried, the 40-something mother of four says that whatever daf she is on always seems to intersect with her life. She recalls a passage in which the rabbis speculate about how they could mandate four cups of wine at the Passover seder. Influenced by Zoroastrian superstitions, Kurshan explains, they had a tremendous fear of anything that came in pairs. “Just at that moment,” she says, “I looked up from my volume of Talmud to discover my 1-year-old twin daughters, who were sitting next to each other in their high chairs, rubbing strawberry yogurt in each other’s hair—and I wondered if maybe the talmudic rabbis were onto something in associating pairs with demonic forces!”

After she finished the first cycle in 2012, she kept learning as if on autopilot. This time around, she learns her daf yomi by listening to the podcast “dafyomi4women” by Michelle Cohen Farber. “Daf yomi is quite literally the soundtrack to my life,” says Kurshan, who writes limericks for each daf. “I listen when I am biking to work, dashing to pick up my kids, jogging, washing dishes, cooking.

“Sometimes,” she adds, “I joke with our Shabbat guests and say, ‘This kugel was brought to you by Bechorot daf 29!’ ”

Farber, 47, who holds a bachelor’s degree in Talmud and Bible from Bar-Ilan University, is a Talmud teacher and co-founder of the modern Orthodox Kehillat Netivot synagogue (where her husband is the rabbi). Seven years ago, the mother of five who lives in the Israeli town of Raanana began the first and, possibly, only daf yomi podcast taught by a woman. She has recorded about 2,000 shiurim and estimates that she has 150 to 200 followers, including some men. She records the podcast at the 45-minute English-language class that she teaches in her home each morning for a group of 12 modern Orthodox women, most of them, like herself, American olim between the ages of 35 and 60. Daf yomi frames both teacher and students’ days, she says. “It’s like a daily workout routine with the added religious and intellectual element.”

The nonprofit organization Farber founded, Hadran—meaning return or review, in Aramaic; the word begins a short prayer upon completing each tractate—promotes women’s Talmud study. On January 5, the group is planning to host its own siyum, gathering up to 3,000 women at the International Convention Center in Jerusalem with the event livestreamed at hadran.org.il.

Not every woman interested in Talmud sticks with daf yomi. Reform Rabbi Amy Scheinerman, 62, who serves as a hospice rabbi in Howard County, Md., and is author of The Talmud of Relationships, found the rapid pace unsatisfying when she practiced daf yomi years ago. She prefers, she says, “a slow and careful engagement with the text, sitting and thinking about it, reviewing it a lot, considering what others say about it and whether I agree, and then returning to dig down to another level.”

Read Amy Scheinerman’s analysis of a Talmudic story, At Dinner With Yalta: A Talmud Lesson.

For her part, Rabbi Avi Strausberg was so afraid she would fail to adhere to her daily commitment that she kept her practice a secret for several months. She began daf yomi in 2012, during her second year of rabbinical school at Hebrew College in Newton, Mass. “I felt like an imposter, because I thought only people with real mastery of Talmud could do daf yomi,” she says.

The 36-year-old describes herself as traditional egalitarian and does not identify with a particular movement. Now living in Washington, D.C., she is director of national learning initiatives for the egalitarian Hadar Institute, which is located in New York City but also runs programs in Washington and Boston. For its siyum, Hadar is planning a day of learning on January 5 in its main offices.

Like Kurshan, Strausberg feels the need to translate her learning in a creative way—for her it’s haiku, and she has written thousands. The structured haiku form (5-7-5 syllables) provides a clear format into which she can crystalize a central thought from the “meandering explosion of words” in a daf, she says. For Bechorot 20, which includes discussions of miscarriage in animals, she wrote: “there is life and death/ possibilities within/ a world in a womb.”

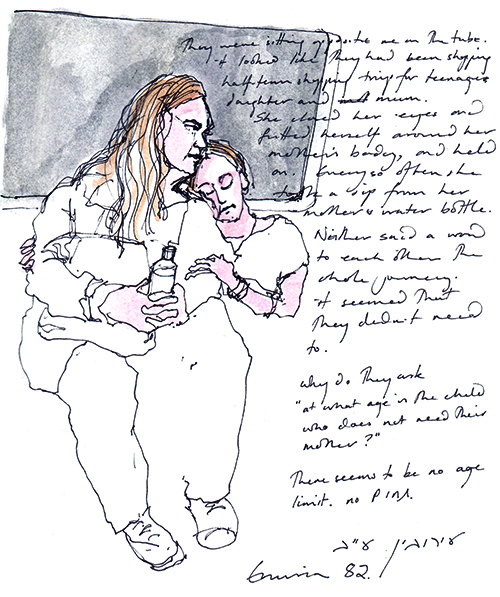

For Jacqueline Nicholls, drawing is a way of taking ownership of the text in a playful way. “I think with pen or pencil in hand,” says the 48-year-old artist who lives in London. “Drawing daf yomi combines beit midrash and art studio. For me, they are the same.”

Nicholls, who was raised Orthodox but today does not associate with any denomination, matches each tractate with different materials: pencil, pen, charcoal, watercolor, even embroidery. In one drawing, on Chullin 21, which discusses the laws of ritual slaughter and is a core component of Orthodox rabbinical training, she transcribed the words in water soluble ink, then introduced water onto the page to dissolve and disrupt the text. “By transcribing this tractate into my handwriting, I am taking ownership of the text that was not given to me,” says Nicholls, who often posts her work on Instagram (@jacquelinenicholls). “The text is ours, and it’s problematic, so we bend it, shape it, argue with it, push and pull it so it’s a living relationship.”

She enjoys the challenge of grappling with the text as a feminist. The Talmud, she notes, does not expect that a woman will be learning it. “It anticipates the person reading it is an educated straight male. It talks about us—but not to us.” In Eruvin 82, for instance, the rabbis conclude that a child no longer needs its mother when it cries in the night and goes back to sleep on its own. “I have children, and that happens when they are quite young. The conclusion is absurd.” Her drawing depicts a teenage daughter cuddling her mother—an actual scene she witnessed on the London tube.

There are times when Nicholls gets so frustrated with the tractate that she is learning that she just wants to shut it. “But it’s part of my intellectual inheritance and cultural identity,” she says. “I have to make sure I’m not going to follow it blindly, but not walk away from it either. It’s a very delicate balance.”

Read our review of The Talmud: A Biography, by Barry Scott Wimpfheimer.

Rahel Musleah, a frequent contributor to Hadassah Magazine, runs Jewish tours to India and speaks about its communities (explorejewishindia.com).

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Moe G. says

If a woman wants to learn Daf Yomi in order to be inspired and to grow, good for her. But many woman quoted here are not interested in learning from the Talmud but using it for their personal benefit or other reasons. This is definitly the wrong intention to learn one of the most sacred texts of the Jewish people.

Also, one must have a Mesora, a tradition, in learning the Talmud. Just opening it and hoping to get it “right” is a foolish way of doing things. There are many aids to getting the true message of what the Great Rabbis of yore were teaching…

Warren B. says

“If a woman wants to learn Daf Yomi in order to be inspired and to grow, good for her.”

How nice of you to offer your approval.

Warren B. says

“If a woman wants to learn Daf Yomi in order to be inspired and to grow, good for her. But many woman quoted here are not interested in learning from the Talmud but using it for their personal benefit or other reasons.”

Oh totally, they should only do it to be inspired and to grow, and not for personal benefits, like… inspiration… or… growth…?

God bless women if this is the kind of circular logic they’re up against.

Iryah Mordechai says

Ho Hum Moe, usual turning woman into witches…at least no more burning them on the stakes ( in the western world ,that is). Stop attacking others motives. Men and Women should learn anything, especially religious texts, with the proper respect.

Moe G. says

I see from your comment that you agree with my assumption that most women are not learning for “the sake of heaven” but for feminist reasons. Feminism, the movement that ripped down the honor of women and gave them worth only in their ability to mimic men, has wrecked havoc on Jewish Women as well and this is what is pushing so many women to learn. So, yeah, i am attacking their poisonous motives and there’s nothing wrong with doing such a thing.

Regarding your second thing, that people should learn with the proper respect, i fully agree. But many of the women quoted here have absolutely none of it. (e.x. Nicholls: “…The conclusion is absurd”) Perhaps if women had more respect for religious texts they wouldn’t feel the need to learn as much, as the “texts” state that Women are respected for the house they build, for the children they raise, and for the support they give their husbands (yes, they should marry). Not the amount of money they make, the fame they receive, or how much they learn.

No, woman are not “witches” when they fulfill the goals that G-d gave them in this world, only when they try to be like men.

Teresa G. says

Perhaps if women had more respect for religious texts they wouldn’t feel the need to learn as much, as the “texts” state that Women are respected for the house they build, for the children they raise, and for the support they give their husbands (yes, they should marry). Not the amount of money they make, the fame they receive, or how much they learn.

Women are learning religious texts because they respect and revere them.That is what the women of Daf Yomi for women are doing. Lots of these women learn in addition to doing what is required of them. and why should a person be denied learning because of their gender?

Yairah Shalhevet says

And let us not neglect a key teaching of all our Mothers, “Don’t feed the Trolls ….” Shabbat shalom shalom l’kulom.