Being Jewish

Commentary

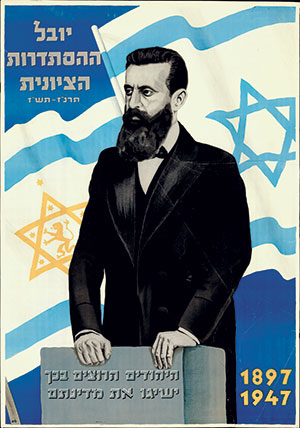

To Fight Anti-Semitism, Look to Theodor Herzl

I struggle to think of a modern Jew more audacious than the 36-year-old journalist who declared in 1896: “The Maccabees will rise again.” So I suspect that many of you, like me, will be surprised to learn that Theodor Herzl’s original answer to the “Jewish Question” then consuming Europe was the furthest thing from a Jewish state.

In 1893, just three years before he prophesized about the new Maccabees in his book Der Judenstaat, Herzl proposed, in the pages of a weekly magazine published by Vienna’s Association for Defense Against Anti-Semitism, that those would-be Maccabees should instead become Christian. There would be, historian Simon Schama writes in the second volume of The Story of the Jews, referring to Herzl’s plan, “a procession in broad daylight to St. Stephen’s Cathedral,” where the Jews would undergo a “mass baptism.” Only a collective conversion to Catholicism would finally solve the anti-Semitic riddle.

Thankfully, it only took a few years for Herzl to wake up from that solution born out of despair. Conversion was not—and could never be—the answer. The only answer was for the Jews to choose life. Whole lives, not partial ones.

“The Jews who wish for a State will have it,” Herzl wrote in Der Judenstaat. “We shall live at last as free men on our own soil, and die peacefully in our own homes.” A year later, in December 1897, Herzl offered a window into his embrace not just of Zionism but of Judaism, in a short essay called “The Menorah.” The subject of the parabolic essay is a successful artist—clearly, Herzl himself—who “had long ceased to trouble his head about his Jewish origin or about the faith of his fathers, when the age-old hatred re-asserted itself under a fashionable slogan.” The artist, like those around him, “believed that this movement would soon subside.”

But it didn’t subside. It only got worse.

“This secret psychic torment had the effect of steering him to its source, namely, his Jewishness, with the result that he experienced a change that he might never have in better days because he had become so alienated: He began to love Judaism with great fervor,” Herzl wrote. “At first he did not fully acknowledge this mysterious affection, but finally it grew so powerful that his vague feelings crystallized into a clear idea to which he gave voice: The thought that there was only one way out of this Jewish suffering—namely, to return to Judaism.”

Why do I revisit this history? What does it have to do with our own fight against anti-Semitism, now rising not only in Europe, but also in the United States, the greatest diaspora the Jews have ever known?

It is because we, like Herzl, face an “age-old hatred” that presents itself in multiple new guises. And so many of us, like Herzl in 1893, are tempted to erase the parts of ourselves that seem unacceptable.

When I meet Jews around the country who confess to me that they are, in one way or another, hiding, I think about Herzl’s original—and deeply human—impulse. Sitting at a dinner party and hearing someone casually note that Israel doesn’t have the right to exist; listening to a colleague complain about the Jewish lobby and its hold on American politics; or even reading about a Hasidic man beat up on the streets of Brooklyn, too many of us feel the same dark desire to disappear.

We tell ourselves that this is not our fight, that standing up for a Jewish state we don’t always agree with or for that religious Jew who looks nothing like us isn’t worth the moral condemnation, social ostracism and reputational vilification we’re likely to receive from our peers. Better to just change the subject.

Herzl felt the same way—until he didn’t.

In the end, Herzl did experience a conversion—a psychological and emotional one. His was a conversion from shame to pride, from accommodation to assertion, from quiet death by assimilation to full life by affirmation. It is a conversion that I believe American Jews, the luckiest in history, must emulate.

There has not been a single moment in Jewish history in which there weren’t anti-Semites determined to eradicate Judaism. But the Jews did not sustain their magnificent civilization because they gave up on their history, faith or values. They surely did not sustain it as anti-anti-Semites.

They sustained it because they knew who and why they were. They were lit up not by fires from without but by the fires in their souls. This, in the end, is the only way to fight against anti-Semitism: by waging an affirmative battle for who we are—for our values, for our ideas, for our ancestors, for our families and for the generations that will come after us.

Few embodied this affirmative battle more profoundly than the father of political Zionism. Several times before his death in 1904, Herzl spoke to a group of Zionists in London who called themselves the Maccabeans. One of their members was a young biochemist named Charles Weizmann. He is known to us as Chaim, the first president of the first Jewish state in the modern era—and the realization of Herzl’s mighty conversion and conviction.

Bari Weiss is an opinion staff editor and writer at The New York Times. This piece is adapted from How to Fight Anti-Semitism, her first book, which has just been published by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Matt McLaughlin says

From the late 19th century and up until World War I, prominent figures such as Leon Pinsker, Theodor Herzl, Ahad Ha’am and David Ben-Gurion—Israel’s first prime minister—all saw the future Jewish territorial unit in Palestine as a province of sorts within the multinational Ottoman. No Jews prior to modern times ever anticipated an ingathering of exiles that would occur without the appearance of a messiah and would result in the establishment of a state in which halakha was not the law of the land. The pious Jews of Palestine—the only kind before Zionist settlement—enjoyed a certain degree of autonomy granted by the sultan. They had never contemplated national status, a concept as foreign to the Palestinian Jews as it was to the Ottoman authorities in Istanbul.