Family

Feature

The Jewish Mother, a Love Story

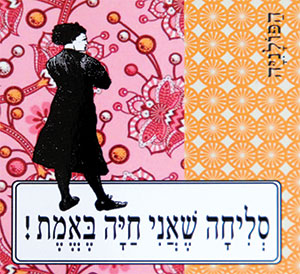

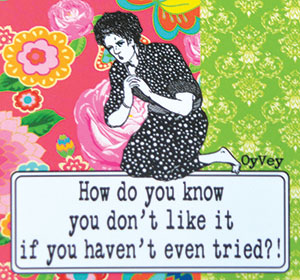

Devorah Blachner is shopping for a birthday present for a friend at a small gift shop on Jerusalem’s tony Bethlehem Road. The 63-year-old Israeli lawyer giggles as she peruses a display of brightly colored magnets. On each magnet is a picture of a woman and a saying, some in Hebrew, some in English.

“At my age, you’re not going to educate me!” Blachner reads aloud from one magnet as she laughs with the shopkeeper. “Is this what I had children for?” says another. Then she points to her favorite: “You’re just lucky I didn’t hear what you said.”

The magnets are produced by HaPolaniya, a Kfar Saba-based gift and design company whose name translates to “the Polish woman”— Israelese for “the Jewish mother” (more on that later).

“I can hear my mother and my grandmother when I read these,” Blachner says with a chuckle. “I was born here in Israel, and I hated having a Polish mother and grandmother who were born in the shtetl. They always said things like this—they were demanding and never satisfied, and always made me feel guilty about everything.”

Lately, exchanging HaPolaniya magnets, aprons, mugs and other paraphernalia as gifts has become “a feminist thing,” she asserts. “It’s kind of a way of being proud of who we are and where we come from. We’re laughing at our grandmothers and mothers, but it’s with so much love.”

Michal Fishbein, the founder, owner and creative designer of HaPolaniya, seems to be on to something. She established her brand in 2013, marketing to Israelis and tourists; it now brings in $500,000 in sales annually. She sells her products at her three HaPolaniya stores as well as in another 50 locations throughout Israel. She is just beginning to market them in the United States under the name OyVey.

The phrases on the merchandise, she explains, come from things that her Polish-born grandmother would say to her. “My grandmother had great lines, filled with love and guilt, very passive-aggressive and very, very funny,” says the 50-year-old Fishbein. “From the way my business is growing, it seems that lots of people had Polish mothers and grandmothers.”

Popular culture is filled with references and jokes about the stereotypical Jewish mother. The traits are familiar to both Americans and Israelis: Self-sacrificing yet demanding, nurturing yet guilt-producing. Gentle yet sometimes mean. Giving but needy. Helpful but destructive. Pushing her children to succeed while holding them back.

Despite the similarities, the image of the Jewish mother developed differently in each country and continues to evolve today. But in both instances, the way the stereotype unfolded reflects the story of American and Israeli Jews, respectively, as they grappled with immigration, family dynamics and identity.

In the United States, the Jewish mother cliché became intertwined with the demands and tensions of the mass Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe in the late 19th and early 20th century, explains Joyce Antler, professor emerita of American Jewish history and culture at Brandeis University and author of You Never Call! You Never Write!: A History of the Jewish Mother. The portrayal has changed as the American Jewish experience has evolved, so that “understanding the Jewish mother is a way to understanding Jewish life in America and the changing face of motherhood,” she says in an interview.

Likewise, in Israel, according to author and journalist Ruvik Rosenthal, Israel’s foremost social linguist, “the way Israelis think of their Jewish mothers reveals much about the development of Jewish and Israeli identity, from the time of the establishment of the state until today.”

Likewise, in Israel, according to author and journalist Ruvik Rosenthal, Israel’s foremost social linguist, “the way Israelis think of their Jewish mothers reveals much about the development of Jewish and Israeli identity, from the time of the establishment of the state until today.”

In both countries, her roots stem from the shtetl, the predominantly Jewish villages peppered throughout Eastern Europe before the Holocaust. In that iconic setting, the Jewish mother was known for her love and self-sacrifice, as revealed in “Oyfn Veg Shteyt a Boym” (There Is a Tree That Stands),” a poem written in 1938 by Yiddish poet and playwright Itzik Manger. It’s about a mother’s worry for her child as he becomes independent and the child’s impatience as he sets out on his life.

The image the poem presents is both loving and tragic. In the face of oppression, poverty, exile and calamity, it was up to the shtetl mother to physically and emotionally nourish her children and protect them from dangers. But devotion was not always enough to guard them against the cruel fates.

According to Antler, the first descriptions of the Jewish mother in popular culture in the United States were affectionate, as in Sophie Tucker’s memorable song, “My Yiddishe Momme.” Similarly, the beloved character of Molly Goldberg, who dominated American radio and television from the late 1920s through the early 1950s, was a benevolent woman who combined Old World love and tradition with modern American expectations.

But by mid-century, Jews were beginning to make it in America, and the traits so necessary for mothers in the shtetl—self-sacrifice, devotion and overprotectiveness—were seen as a burden by their American-born children. This disrupted traditional gender and family dynamics, Antler explains, and new generations of comedians and social scientists created a portrait of the Jewish mother as backward, manipulative, demanding, guilt-inducing and never satisfied.

Much of this caricature was burnished, Antler says, in the nightclubs of the Catskills resorts. There, thousands of first- and second-generation American Jews, rejected by hotels that were open to non-Jews only, spent their summers entertained by Jewish performers and comics.

“Because most of the entertainers were men, they were able to project their anxieties about fitting into American society onto their mothers,” Antler says. “When the men made fun of their mothers, it was with bitterness, hatred and misogyny. There was, of course, a kernel of truth, as there is in all stereotypes, but often the humor was mean and nasty.”

Ridiculed and scorned, the Jewish mother was often compared to a vulture (because she eats your heart out), a Rottweiler (because she never lets go) and a terrorist (with a terrorist you can negotiate).

As time went on, the Jewish mother image warped even more. Books such as Dan Greenberg’s How to Be a Jewish Mother, published in 1964, includes quips like “You don’t have to be Jewish to be a Jewish mother—but it helps.” The book contributed, Antler says, “to the sense that Jews were ‘others’—different from mainstream American culture and society.

“It wasn’t funny anymore, at least not for Jews and certainly not for women,” Antler continues. “And some of it was clearly anti-Semitic, a reaction to the successes that Jews achieved in America, attributed, at least in part, to their mothers, who made sure their children did well.”

In Portnoy’s Complaint, published in 1969 and made into a film in 1972, author Philip Roth brought the negative stereotype of the Jewish mother to its lowest point, Antler asserts. In sessions with his therapist, Portnoy blames all of his failures—his poor choices with women, his flailing career, his sexual obsessions and impotence—on his mother. While some Jewish scholars praised the book—which sold over six million copies—as a brilliant exploration of Jewish identity in late-20th-century America, Antler notes that Roth’s portrayal of Jewish mothers was both “misogynistic” and “hateful.”

In the years since, the image has changed again, softened by feminism and cultural maturity, Antler says. “As contemporary Jews become more confident, they can see their mothers more clearly and confront distortions that troubled previous generations,” she explains. The popular sitcom The Goldbergs, based on the life of its creator, Adam Goldberg, and currently in its sixth season, depicts his mother, Beverly, as lacking boundaries and overprotective—but in a loving way.

“And as women writers and comedians became more powerful,” Antler says, “they made the connection to our mothers that the men never did. The men’s humor was derisive; the women’s humor is connected.”

In You Never Call! You Never Write!, Antler cites works such as The Sisters Rosensweig, by the late playwright Wendy Wasserstein, in which mothers were reinterpreted and transformed in an effort to understand and bond with them. Indeed, today, feminist women seek to reinforce their identity as Jewish women through their love of their grandmothers and mothers. Antler notes, for example, that while female Jewish comedians—Judy Gold; Jackie Hoffman, who is currently playing Yente in the Yiddish version of Fiddler on the Roof Off Broadway; and Sarah Silverman, to name a few—still poke fun at the stereotype, they also sympathetically present a more fully developed image.

Judy Gold, in fact, was featured on an early episode of the new podcast Call Your Mother, which embraces the Jewish mother in all its modern complexity. The title is a “nod to the very stereotypically Jewish concept of a mom,” says Shannon Sarna, the editor of The Nosher, a food blog, who co-created and co-hosts the podcast with Jordana Horn, a writer and attorney. But the goal of the podcast, sponsored by Kveller, a parenting blog, is broader, she says: “to provide a point of connection for Jewish parents, to have honest conversations about the modern joy and challenges of Jewish parenting as well as share diverse narratives of Jewish parenting.”

In Israel, “the Polish mother” evolved differently than her American Jewish counterpart. In 1941, Israeli poet and playwright Nathan Alterman published “A Letter From Mother,” a poem in which a mother in pre-state Israel writes to her soldier-son serving with foreign troops in World War II. Soon set to music, the song became an immediate hit, presenting a flip-side to Sophie Tucker’s paean to her mother. In the poem, the mother cautions her son to be careful and wear a sweater, to capture only one tank at a time, to advance and then to rest—and to write more often to his dear, loving mother. With multiple cover versions, “Letter” is still a popular song, now seen as referring to Israeli soldiers engaged in the Israeli-Arab conflict.

Still, the traits of the Israeli Polish mother and the American Jewish mother are nearly identical, says Irit Kleiner-Paz, a clinical psychologist in Israel who has written on these issues. She refers to the well-known joke about the mother who, instead of getting her kids to change a lightbulb, chooses to sit in the dark. “Of course, the mother needs light, just like everyone else,” she says. “But most Jewish women were not allowed to develop their own talents and skills, and society demanded that they not express their own needs and desires. So they projected everything—frustrations, hopes, ambitions, disappointments, passions—onto their children. And they did so passive-aggressively and manipulatively, because social norms did not allow them to express themselves directly.”

In contrast to the development of the Jewish mother in America, in Israel, references to the Polish mother only began to appear in popular culture in the 1980s, says Rosenthal, the Israeli linguist.

Speculating on the differences between the two countries, he notes that while the majority of Eastern European Jews came to the United States before the Holocaust, the majority immigrated to Israel afterward.

“It’s not that we didn’t know about the stereotype or that on a personal level, many of us didn’t have Polish mothers,” Rosenthal explains, “but it seemed wrong to laugh at them. In the shtetl, Jews could laugh, and Jewish humor was famous as a coping mechanism for the difficulties of life in Eastern Europe, but here in Israel it was too sad, too painful.

“Young children would hear popular radio shows like Looking for Missing Relatives, in which people who had survived the Holocaust were searching for their relatives and loved ones,” he adds. “It wasn’t funny to laugh about overprotective mothers whose children had been murdered. It takes distance and time to develop cultural laughter.”

Still, like in the United States, where newly arrived Jews yearned to become American, young Israeli Jews, whether born in Israel or born just after the Holocaust in Europe, wanted to acculturate into modern Israel. “Following the Zionist ethos, we thought of ourselves as new Jews—proud, strong and free from the fears of the shtetl,” Rosenthal says.

But even as the concept of the Polish mother took hold, it was much kinder and softer than in the United States, without any of the rancor and rage that characterized, for example, Portnoy’s Complaint. “By the time they could laugh at their mothers, Israelis weren’t so arrogant and cocky anymore,” Rosenthal says. “Israelis had experienced loss, especially after the Yom Kippur War. We no longer felt the need to reject everything in the Diaspora.”

And, adds HaPolaniya’s Fishbein, the attitude toward Yiddish—the language in which most of her magnet expressions were first uttered—had changed, too, allowing for a deeper connection to the previous generation of Yiddish-speaking mothers. “In the first years of the State of Israel, Yiddish was practically banned because we were supposed to be speaking Hebrew and our parents and grandparents spoke Yiddish in secret,” she says. “But as Israeli society matured, we were more accepting of Yiddish and our parents’ culture.”

Although she writes the expressions on her merchandise in Hebrew and English, “when I think of them, I hear my grandmother saying them in Yiddish,” she says, noting that the humor works in Ladino and Moroccan Arabic as well. “Maybe it is the language of minorities, who, because they fear persecution from the majority, have to say things indirectly, or use the same phrases for multiple levels. Yiddish lets you cry while you laugh.”

Although the Jewish/Polish mother does not appear in comedy, film or literature in Israel as often as she does in the United States, the stereotype is still well-known. “We know the sayings, we’ve heard them, we’ve laughed about them,” says Blancher, the lawyer buying the magnets. “Last week, a friend sent me a text message saying that she would not be offended if I didn’t attend an event we were supposed to be going to. And then she sent another text, saying, ‘I didn’t mean that in a Polish way.’ ”

But with so many different cultures that make up Israeli society, how did the Jewish mother in Israel become Polish? “Obviously,” quips Rosenthal, “we couldn’t call her a Jewish mother, since most mothers in Israel are Jewish.” And just like you don’t have to be Jewish to be a Jewish mother in the United States, you don’t have to be Polish to be a Polish mother in Israel. It’s not unusual to hear Israelis whose parents came from Morocco or other Sephardi lands referring to their mother’s smothering concern as Polish.

Rosenthal acknowledges that the question of how “Jewish” morphed into “Polish” remains “a bit of a cultural mystery. But somehow, it seems to make sense.”

For her part, Fishbein says she is happy that her products are striking a chord with Jews wherever they live and are contributing to “a recognition of our culture in all its complexity.”

“Someone told me that they used my mugs at the shiva for their grandmother because it allowed them to laugh lovingly about her,” she recalls. “My grandmother would have liked that.”

Eetta Prince-Gibson is an award-winning journalist and former editor-in-chief of The Jerusalem Report who now writes for Israeli and international publications.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram Twitter

Twitter

Leave a Reply